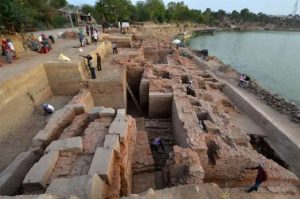

As the world continues to feel the profound effects of climate change in increasing orders magnitude, remote and vulnerable communities are feeling the brunt of the consequences. The Himalayan village of Komic in India’s mountainous far north, the so-called “world’s highest village,” is no exception. Retreating glaciers and unseasonably weak snowfalls are testing the limits of fragile Himalayan ecosystems and already scarce water resources are approaching crisis point.*

Perched at an elevation of 4,587 meters in the arid Spiti Valley in the state of Himachal Pradesh, where India bumps up against Tibet, Komic lays claim to be the highest village in the world accessible by a motorable road. Life for the village’s some 130 residents, who subsist primarily on agriculture, has never been easy, yet recent years have borne witness to increasingly severe droughts as life-bringing glaciers retreat, snowfall declines, and streams and lakes dry up.

“Water isn’t an issue so long as we receive snowfall in peak winter. But that is not happening and our glaciers, too, are melting faster than before,” said 56-year-old farmer Nawang Tandup, gesturing toward the dry grey-brown slopes of a mountain some 10-kilometers distant that provides the community’s primary supply of water. “We are now hoping for some divine intervention.” (The Indian Express)

Communities across the valley’s upper catchment area—Chicham, Kibber, Tashigang, Gette, Langza, Hikkim and Demul—are equally vulnerable to what is becoming the new normal as natural resources dwindle. With a population of some 12,000 people, Spiti Valley possesses a distinctly Tibetan culture centered on Vajrayana Buddhism, similar to that found in the Ladakh region of India and nearby Tibet. The valley forms part of a cold Himalayan desert that is cut off from the rest of India for six months of the year when the region’s lofty mountain passes are blocked by snowfall.

The Tibetan Plateau is one of the world’s most sensitive and vulnerable climate change hotspots. Home to some 46,000 glaciers, the Tibetan Plateau is sometimes referred to as the Earth’s “third pole” as it contains the largest concentration of frozen water outside of the planet’s two polar regions. These glaciers feed many of the region’s great rivers, including the Ganges, Mekong, and Yangtze, which supply water to a third of the world’s population. Over the past 50 years, temperatures on the Tibetan Plateau have risen by 1.3ºC—three times the global average—causing glaciers to retreat, permafrost to deteriorate, and grasslands to degrade, accompanied by increasing desertification. Some studies have projected that as much as two-thirds of the region’s glaciers could disappear by 2050. Coupled with erratic rain and snowfall, warmer temperatures are taking their toll, with rivers, streams, and lakes rapidly drying up.**

Numerous scientific studies have highlighted to the potentially catastrophic impact of climate change in the Himalayan region. Just this year, research published in June concluded that Himalayan glaciers have lost half a meter of ice each year since 2000—far faster than in the previous 25-year period—an in recent years, some eight billion tons of water a year has been lost as a result.

In February, a report produced by the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development repeated earlier warnings that the Himalayan mountains could lose up to a third of their ice by the end of this century—and then only if the world is able to attain its most ambitious climate objective of limiting the rise in average global temperatures to just 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels. A goal that most experts agree is so far not even close to being met. Meanwhile in May, a further study concluded that Himalayan glaciers are melting faster in the warmer summer months than they are being replenished by snow in winter.

In the village of Komic, district agriculture official Anil Kumar noted that the effect on farm output has been dramatic, threatening livelihoods and food security.

“There has been a roughly 30 per cent drop in the yields of jau [barley] and matar [green peas] in these villages over the last five years,” he said. “Snow should ideally stay at the source from December to February. Also, there should be sufficient snow on the fields during March–April, without which sowing gets delayed.”

“Everything,” he emphasized, “is dependent on snowfall.” (The Indian Express)

* Climate Change in the Himalayas Signals Drought for the “Highest Village in the World” (Buddhistdoor Global)

** Dalai Lama Heads Call for International Action on Climate Change (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Climate change in Spiti: Water crisis engulfs world’s ‘highest’ village (The Indian Express)

Spiti freezes at -18°C, coldest night bites Manali (The Times of India)

Rising Temperatures Ravage the Himalayas, Rapidly Shrinking Its Glaciers (The New York Times)

World’s ‘highest’ village runs dry as warming hits the Himalayas (Reuters)