Professor Duncan Ryuken Williams, professor of Religion and East Asian Languages & Cultures and director of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions at the University of Southern California, was awarded the Grawemeyer religion award, according to an announcement last Friday. The award, jointly given by The University of Louisville and Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, carries with it a prize of US$100,000. The prizes honor seminal ideas in music, world order, psychology, and education.

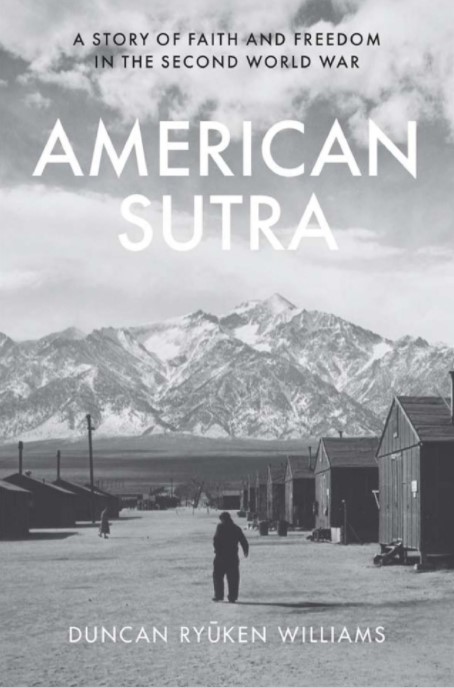

Williams won the prize for ideas he put forth in his book, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press 2019). In addition to his scholarship, Williams is a Soto Zen Buddhist priest.

In the press release Tyler Mayfield, director of the Grawemeyer religion award, said, “Williams’ work opens the way for a discussion that values religious inclusion over exclusion. He shows how Japanese Americans living in a time of great adversity broadened our nation’s vision of religious freedom.”

In the book, Williams reviewed the diaries of people of Japanese ancestry who were imprisoned by the United States government after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, 1941. Some 125,000 individuals of all ages and walks of life were rounded up from across the country and relocated to detention camps in the U.S. Two-thirds of those imprisoned were Buddhist practitioners.

Williams documents the heartbreak and loss faced by those detained, with many taken away with few belongings and only hours to prepare for an uncertain journey. He also gives light to the joy and hope found among those imprisoned. He showed that they still practiced Buddhism in confinement, in one case celebrating a Buddhist holiday with a Buddha carved from a carrot, surrounded by a “cherry blossom flower arrangement” made from beet-dyed toilet paper.

“Their imprisonment became a way to discover freedom, a liberation that the Buddha himself attained only after embarking on a spiritual journey filled with obstacles and hardships,” Williams said in a press release.

In the book, Williams wrote that, “The Buddha taught that identity is neither permanent nor disconnected from the realities of other identities. From this vantage point, America is a nation that is always dynamically evolving—a nation of becoming, its composition and character constantly transformed by migrations from many corners of the world, its promise made manifest not by an assertion of a singular or supremacist racial and religious identity, but by the recognition of the interconnected realities of a complex of peoples, cultures, and religions that enrich everyone.”

It is out of the unique experience in America by those of Japanese ancestry that Williams argues an American Buddhism arises. BDG contributor, Harsha Menon, interviewed Williams on the book when it came out in 2019.

In the interview, Williams said that:

People during WWII drew on their Buddhist faith to help orient them at a time of dislocation and loss. I’ve found that how we orient ourselves in the world and narrative stories about ourselves is also a critical part of walking the Buddhist path. I believe the post-publication storytelling work has been an important part of making sure that the Buddhist individuals and families who enduring much suffering are not erased from history, but rather celebrated as important pioneers of American Buddhism.*

* American Sutra: On the Incarceration of Japanese Americans in WWII (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Duncan Ryuken Williams wins 2022 Grawemeyer Religion Award (Louisville Seminary)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

What American Buddhism Looks Like: Solidarity for Immigrants at Fort Sill

Why Fold Paper Cranes? Japanese American Buddhists and Today’s Migrant Crisis

Tsuru for Solidarity Takes Peaceful Action to Protest Mass Detention of Immigrants in the US

The Birth of an American Form of Buddhism: The Japanese-American Buddhist Experience in World War II

Related news reports from Buddhistdoor Global

The Birth of an American Form of Buddhism: The Japanese-American Buddhist Experience in World War II