Whether it is his unconventional performance art, his photography, or his sculpture, Chinese artist Zhang Huan’s remarkable repertoire is rebellious, eccentric, controversial—and spiritual, particularly in relation to Tibetan Buddhism. His dramatic style can easily be identified as a manifestation of his own avant-garde persona and his early experiences in life.

Born in 1965 in Anyang, in China’s Henan Province, he was relocated the following year with the launch of the Cultural Revolution to a small commune in the countryside, where he lived with his paternal grandmother until the age of eight. He then rejoined his parents in Anyang, a bustling city of almost 5 million people. In an interview with art historian and author Roselee Goldberg, Zhang described himself as an unruly child: “I was a wild child in the classroom. I couldn’t stay indoors. I wasn’t interested in the subjects, I was always asked to leave the room. I drew all the time” (Zhang Huan).

Zhang received his BA from Henan University in 1988, where he studied Chinese ink painting, drawing, oil painting, and art history. At the age of 26, he moved to Beijing to further his studies in oil painting, obtaining his MA from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1993. Zhang then quickly carved out a niche for himself as one of the first performance artists in China. According to Goldberg, once he arrived in Beijing he “abandoned traditional painting and began solo performances that were executed in the nude and frequently involved extreme endurance and danger.” His early groundbreaking performances include 65 Kilograms and 12 Square Meters, which represented a turning point in contemporary Chinese art. He also met and was inspired by many other avant-garde artists, both local and foreign. In 1988, Zhang moved to New York, and was based there for the next eight years. He then returned to China and settled in Shanghai, where he switched his attention back to object-based art.

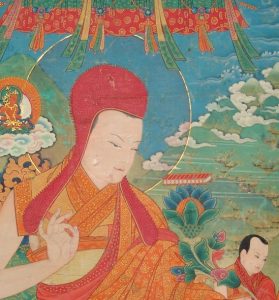

As well as social commentary, Zhang Huan’s artistic themes include the Buddha, Buddhism, Tibet, and deep spirituality.

A Buddhist himself, he reminisces about his early childhood when religious ceremonies were prohibited in public. However, as he admitted to Roselee Goldberg, “Spiritualism was acted out in various Chinese festivals and ceremonies. Every year for example, we would make an altar in the home to honor the New Year. We would light incense, paste prayers in the form of posters on the walls of the house, take a meal to the graves of our ancestors. . . . Actually, I come from one of the highest areas of Buddhist concentration and my biggest spiritual influence was Tibetan Buddhism” (Zhang Huan). Zhang has created a number of colossal artworks that portray Buddhist iconography, including the Three Legged Buddha (2007), Berlin Buddha (2007), and Three Heads Six Arms (2008).

The inspiration behind Zhang’s Three Legged Buddha originated from a visit to Tibet. “I collected a lot of fragments of Buddhist sculptures in Tibet [that had been destroyed or looted during the Cultural Revolution]. When I saw these fragments in Lhasa, a mysterious power impressed me. They were embedded with historical traces and religion, just like the limbs of a human being” (Emaho Magazine). Made of steel and copper, this 28-foot-high, 12-ton sculpture was first displayed in 2007, in the Annenberg Courtyard at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. The massive structure depicts the lower half of a Buddha torso with three legs, one of which rests on the upper half of a human head. Journalist Susan DeMark describes this piece as “an artwork of mystery and complexity. It captures life, death, and rebirth. The enormous sculpture is strong and muscular, yet fragile; seemingly dominated yet defiant. Is the key figure within it collapsing, or is it arising?” (Mindful Walker). On his website page about the installation in London, Zhang himself explains: “According to the world of Samsara, Buddha is human, human is Buddha. Causality produces effects. I hope that this Three Legged Buddha from the East will bring harmony to London and the world” (Zhang Huan). The Three Legged Buddha was displayed in London until 2008, after which it was moved to the National Opera of Belgium in Brussels in 2009, and then to the Storm King Art Center in New York in 2010.

Berlin Buddha, in contrast, comprises a pair of Buddha sculptures that sit facing each other across the room: one of aluminum and one made from incense ash. The ash Buddha was created using the 12-foot-tall hollow aluminum Buddha as the mold, which was filled with six tons of incense ash gathered from temples in Shanghai. Once the ash had compacted and settled, the mold was removed piece by piece and reassembled across the room. Without its outer protective layer, the ash Buddha is allowed to slowly crumble over time. What an astute representation of impermanence! Zhang Huan shares the concept behind Berlin Buddha and his use of incense ash as a medium in his artwork: “Berlin Buddha conveys the idea of samsaras—of life starting from birth, senility, illness, and death till rebirth. Taking the ash burnt in religious rituals as a medium of artwork is also a kind of inevitable samsara. In my eyes, ash carries the believers’ hope and soul, and the ash artworks convey the collective memory, collective soul and collective blessings of the people of China” (Emaho Magazine).

Three Heads Six Arms, which at 15 tons is one of Zhang’s largest sculptures so far, was created to reflect the changing realities of people living in China today. Zhang says, “It reflects the attitude of humankind having conquered nature and even reflects deeds of volition and hope” (Emaho Magazine). Inspired by Tibetan Buddhist sculptures, the work has three heads, two of which are human, including one portraying Zhang himself.

Most recently, on 7 January this year, another pair of Zhang’s giant ash and aluminum Buddha sculptures was installed in Sydney under the name Sydney Buddha. The aluminum mold—this version standing at over 16 feet—with its incense-ash twin had previously been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Taipei, under the name Taiwan Buddha (Artnews).

It is now over a decade since the figure of the Buddha first appeared in Zhang’s work, with his 2004 installation Dharma Circle. Since then, he has continued to evoke the parallel worlds of spirituality and inner meaning. In an interview with Zhang in 2008, art curator and writer Pernilla Holmes states, “While the Three Legged Buddha and Berlin Buddha invite various socio-political readings of these works, what is perhaps most striking is Zhang Huan’s uncompromising humanism, an insistence on foregrounding compassion, pain and transcendence over religion and politics.” She goes on to note that his more recent ash works “have a meditative quality that feels very different from [his earlier] more confrontational performance works.” Zhang himself responds in the interview with the declaration that, “The development of my work is coincidental with my spiritual development. . . . After becoming Buddhist . . . I have created more works that directly take Buddha as their subject. In these works, you can feel a stronger sense of that calm or meditative quality, and a deeper spiritual significance in them as well” (Zhang Huan).

Zhang Huan continues to create innovative, skillful, and unconventional pieces that are highly thought provoking and which inspire us to deeper contemplation of humanity and the meaning of life.

“There is nothing that never changes” Zhang Huan (Artnet).

For further information, see:

Zhang Huan: The Man with Three Legs (Emaho Magazine)

Encountering the “Three Legged Buddhardquo; (Mindful Walker)

Storm King Installs Newly Acquired Monumental Sculpture by Zhang Huan (artdaily.org)

Chinese artist Zhang Huan’s ash sculpture, “Berlin Buddha, Unveiled at Art Stage (Blouin Artinfo)

Interview with Zhang Huan by Rosalee Goldberg (Zhang Huan)

Biography (Zhang Huan)

Three Legged Buddha (Zhang Huan)

Berlin Buddha (Zhang Huan)

Three Heads Six Arms (Zhang Huan)

Zhang Huan’s Sydney Buddha Astonishes at CarriageWorks (Artnet)

Beyond Buddha, Zhang Huan in Conversation with Pernilla Holmes (Zhang Huan)