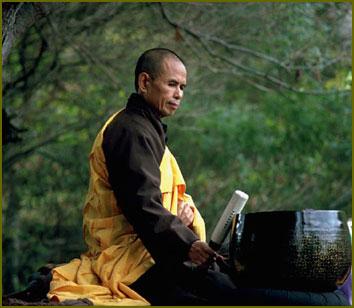

Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh is, beyond a trace of doubt, a spiritual and moral luminary for several generations. He walks a path of social justice, global healing, and interfaith understanding that has been shared by others, such as the late Martin Luther King Jr. and Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar. This path is not an easy one, and is often fraught with scarcity of resources and popular or political support, cynicism, and in some regions of the world, actual physical danger. Throughout history, the path of peace has often been cruelly cut short by murder, corrupted by vested interests, or distorted by misunderstanding. But Nhat Hanh’s ordained name describes his vocation perfectly. No matter how difficult or how dangerous, there can only be one path for this monk to walk – a solitary one, beyond life and death. There is only one path he wishes to walk, because it embraces all other paths and transforms them into something existentially meaningful and spiritually worthwhile.

A man who shared Nhat Hanh’s path was Thomas Merton. Merton was a Trappist monk who has exerted an impressive influence on the development of a modern Catholicism open to conversations between different denominations of Christianity and different religions. When I wrote a thesis on moral commonalities between Shantideva and Merton, I was struck by the later Merton’s honest attempts to understand Buddhism. Some of his work during this time was in fact devoted to refuting Western ideas about Buddhist teachings being pessimistic or life hating. He concluded that they are in fact extremely solicitous for life (Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 93). Most fundamentally, they penetrate the meaning and reality of suffering using meditation and wisdom, and protect all beings against suffering by nonviolence and compassion. They help people to rise above the domination of processes and natural necessities, and to “study and judge the forces of passion and delusion that go into operation” when they confront the world in their isolated egos (Merton, Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 90). Such an evaluation of Buddhism is surely fair by any Catholic or non-Buddhist standard, and it would not be surprising to find many Buddhists agreeing with such an assessment too.

Thich Nhat Hanh only met Merton once, but he made a lasting impression on the Catholic priest. The latter was growing increasingly frustrated with the United States’ bloody involvement in the Vietnam War and the relative silence of the Church he served. Indeed, he declared that Nhat Hanh was more his brother than many other Americans or British, because they saw things “exactly the same way” (Nhat Hanh is my brother). They both deplored the Vietnam War, and both knew that the true answer to peace could not lie in American military might and aggression. For Merton, the real answer to lasting peace lay in the freedom of humanity to choose authenticity. He believed that Thich Nhat Hanh’s spirituality could provide this freedom because he acts as a free man and is moved by the “spiritual dynamic of a tradition of religious compassion.” The figure of Nhat Hanh is reminiscent of wise men that have come before him (“from time to time,” in Merton’s words), “bearing witness to the spirit of Zen.” Thich Nhat Hanh showed the world that Zen is neither world denying nor esoteric, but has its own, rare sense of responsibility in contemporary society (Nhat Hanh is my brother).

Although masters from different traditions have unique perspectives on the nature of their work, their vocations can, on many occasions, intersect. Merton put it beautifully in his essay: they were both monks, monastics with religious authority in their respective faith communities. But they also wrote poetry to express their spirituality. They were existentialists in the general sense – deeply reflective on the interconnectedness of the universe and its complex multiplicities. The conclusion, for Merton, was clear: “I have far more in common with Nhat Hanh than I have with many Americans, and I do not hesitate to say it” (Nhat Hanh is my brother). It is a happy fact that he was right.

Since Merton’s premature death, Thich Nhat Hanh has written several important books that match Merton’s energy for seeking to understand a different faith. Most prominent among these are Living Buddha, Living Christ and Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers. Like most of Merton’s writing, they are not systematic theology nor are they intended as such. Thich Nhat Hanh is a philosopher in his own special way, speaking to the heart of bodhi rather than mere intellect. And in many ways, that is what Nhat Hanh has done throughout his entire vocation as the epicenter of Vietnam’s conscience and founder of Europe’s largest and most vibrant sangha, Plum Village. His work addresses the entire human being because for him the Buddha is a reality that dwells in all beings.

Buddha is right here; we don’t have to go to the Vulture Peak. We are not deceived by mere outer appearances. For me, Buddha is not just a form or a name, Buddha is a reality. I live with the Buddha every day. When eating, I sit with the Buddha. When I walk, I walk with the Buddha. And while I’m giving a Dharma talk, I’m also living with the Buddha.

I wouldn’t exchange this essence of the Buddha for a chance to see the outer form of the Buddha. We shouldn’t rush and call the travel agency to fly to India and climb up the Vulture Peak to see the Buddha. No matter how seductive the advertisements may be, they can’t deceive us. We have Buddha right here” (The Energy of Prayer, 66 – 7).

This passage, to me, offers one of Thich Nhat Hanh’s most important insights (I have referenced it before, and I intend to continue doing so). It is similar to Merton’s own experience of the Buddhas at Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka, which was perhaps the most profound spiritual experience of his later life: “The rock, all matter, all life, is charged with dharmakaya… everything is emptiness and everything is compassion” (Merton, Asian Journal, 233 – 6). There exists, therefore, an unmistakable unity in Nhat Hanh’s expression of Buddhism, so close and familiar that others also have experienced it, even if they do not know. Is it any wonder that the Zen Master is truly “a Man for All Faiths”?

Quotes of Nhat Hanh is my brother were taken from King, Robert H. Thomas Merton and Thich Nhat Hanh: Engaged Spirituality in an Age of Globalization. New York and London: Continuum, 2001. 107.