One of the most visited sites in Kyoto, by Japanese tourists as well as by foreigners, is the temple Ryoan-ji in the northwestern part of the city. Its dry garden is the most famous and probably the finest example of the Japanese kare-sansui (dry landscape) garden tradition, in which elements of nature such as mountains and rivers are stylized and miniaturized using large rocks and gravel. Because many of these gardens are on the grounds of Zen Buddhist temples, they have become known in the West (but not in Japan) as “Zen Gardens” and have become a worldwide symbol of the stillness and focus of Zen meditation. They can now be found not only in Japan but also in Japanese-style gardens throughout the world, and are even available in miniature as a desk ornament—presumably to help focus the mind before a day’s work in the office.

Dry landscape gardens first appeared as elements of Japanese garden design as early as the 8th century. They became more prevalent in the Heian period (784–1185) and were influenced by gardens in China, where groups of rocks were often arranged to represent the island of the Immortals, Mount Penglai (J. Horai-san), and figures and places associated with Chinese Daoist beliefs. In the gardens of the Japanese nobility of the Heian period, the cleverly placed rocks evoked dramatic mountains and gentler hills, and sand and gravel suggested streams, rivers, and the ocean.

The Chinese influence on Japanese gardens continued over the centuries. In the late 12th century, Japanese Buddhists traveled to southern China to study a meditational form of Buddhism called Chan, which they brought back to Japan and renamed “Zen.” The military elite, who had taken over the rule of the country from the imperial court, soon embraced this form of Buddhism because of its emphasis on simplicity, austerity, and living in the moment, a concept to which samurai warriors could well relate since they had to be prepared to face death at any time. Under warrior patronage, Zen Buddhist temples were founded in the first military capital of Kamakura (near modern Tokyo) and later in Kyoto. The gardens of Japan’s early Zen temples resembled the most popular Chinese gardens of the time, with lakes and islands, rocks, plants, and flowers. However, in the 14th and 15th centuries, after the military capital had been moved to Kyoto, some of Japan’s major Zen temples began to feature spectacular dry gardens on their grounds, too.

Zen Buddhists believe that representations of nature can assist a practitioner in his or her meditation and pursuit of satori, or sudden enlightenment in this life. Bold ink landscape paintings created by some of the finest contemporary artists from China and Japan were used by Zen adepts to help in their practice. In these paintings, key elements of a natural landscape—mountains, rivers, mist, trees—were simplified and abstracted. This provided practitioners with a focal point during seated meditation, or zazen, allowing them to shed the material distractions of the world and access the truth of reality. It is possible, though not certain, that the dry landscapes in Zen temple gardens also served this purpose, though it is more likely that they served to help still the minds of the practitioners as they made their way to the meditation hall. The Buddhist monk and garden designer Muso Kokushi is credited with designing the first true “Zen Gardens” of Kyoto, most famously the upper garden of the temple Saiho-ji, which was originally designed in the 1330s as a dry rock garden featuring three rock “islands”: Kameshima, the island of the turtle, which resembles a swimming turtle; Zazen-seki, a flat “meditation rock” that radiates calm and silence; and Kare-taki, a dry “waterfall” built of layered flat granite rocks. The temple is now popularly known as Koke-dera, or the “Moss Temple,” because of the moss that grew over Muso’s dry landscape when the temple was abandoned centuries later. Now, the moss surrounds the three islands and is considered to represent water.

An entirely different dry garden, created over a century later, is the gravel garden at Ginkaku-ji, or the Temple of the Silver Pavilion, built in the Eastern Mountains of Kyoto in the late 15th century. Beside the temple’s traditional pond garden, the temple grounds also feature an area of raked gravel with a mountain in the center (added to the gravel landscape in the 17th century), resembling Japan’s famous Mount Fuji surrounded by a tranquil ocean. This raked-gravel style was revolutionary, as the patterns raked into the gravel were geometric and stylized rather than an attempt to recreate nature, and the style has been imitated as a decorative element in many Japanese gardens since.

The most famous of all the dry landscape gardens was created at Ryoan-ji in the 16th century. Combining the raked gravel seascape of Ginkaku-ji with the rock islands of Saiho-ji, this highly abstracted landscape was set in a rectangular space next to the veranda of the abbot’s residence. A total of 15 stones are arranged in five groups consisting of five, three, three, two, and two stones. Although the landscape is designed to be viewed from the veranda, the entire composition cannot be seen at once from any vantage point. Only 14 of the boulders are visible at one time, creating a sort of visual koan or conundrum. According to the mythology of the temple, only through attaining enlightenment can a practitioner see the 15th stone, too.

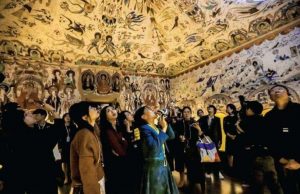

Today, because of the hordes of tourists who file through the garden grounds every day, it is difficult to imagine being able to find peace and calm gazing upon the stone and gravel formations of Kyoto’s Zen temples. However, in their day, these gardens were once oases of tranquility. When practitioners of meditational Buddhism were not seated on tatami mats in the meditation hall, fixing upon abstracted monochrome ink landscapes, they could be found pausing on the veranda to contemplate the abstracted natural formations in the garden before them and connecting their minds with the universe.