Young Voices is a special project from Buddhistdoor Global collecting insightful essays written by high school students in the US who have attended experiential-learning-based courses rooted in the Buddhist teaching. Inspired by and running in parallel with BDG’s Beginner’s Mind project for college students, Young Voices offers a platform for these students to share essays expressing their impressions and perspectives on their exposure to the Buddhadharma and its relationship with their hopes, aspirations, and expectations.

Leo Peters wrote this essay for his “Global Buddhisms” class at Phillips Andover, a high school in Massachusetts.

On My Life as a Smartphone-less High School Student

Even from outside I could hear the raucous noise of people chatting and laughing with their friends. I knew that I didn’t want to walk inside the cafeteria now, all by myself, with no idea who I was going to sit with. I wanted to text someone and find out where they were first. But I didn’t pull out my phone. I didn’t turn around. Instead, I stepped into the room.

“High school is an ideal time for packs,” Clare Sestavonich writes in her novel Objects of Desire. “Everyone is weak; everyone wants strength in numbers.”

To me, this feels true most of all in my high school cafeteria, where sitting alone can be almost scary. No one wants to sit alone; everyone wants to find their pack.

Today, though, I couldn’t find my pack. I felt anxious—as if I was in danger. I was afraid that I would walk into the cafeteria and not have anyone to sit with. I was afraid that I would have to sit by myself, and when other people saw, they would judge me. Normally, when I feel afraid (or tired or bored or angry), I can pull out my phone to distract myself—or even find someone to talk to. This time, I couldn’t do anything. I didn’t have my phone at all because I had given it up for my Global Buddhisms class, in an attempt to examine how I related to my emotions. With no other choices, I was forced to confront my anxiety directly.

I walked into the cafeteria and got in line. While I would normally go on my phone when waiting in line, this time I talked to the people around me. Then, after getting my food, I stepped into the sea of chairs and tables. Eventually, I found some people I knew just well enough to sit with. As I couldn’t go on my phone, I was also forced to sit with my anxiety. After a while—when nothing terrible happened—I realized that even my anxiety was something I could sit with. Even better, I could learn to get along with it well enough; I didn’t have to avoid it all the time.

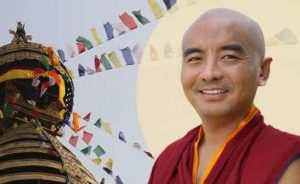

Around the same time that I gave up my phone for class, I was learning about the importance in Buddhism of relating to our suffering or discomfort in a way that will not reproduce these feelings. For example, in his book In Love with the World (Random House, 2019), Tibetan Buddhist monk Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche describes how people normally avoid situations they are afraid of, such as big crowds or heights. However, Rinpoche observes, “the causes that provoke these responses do not go away; and when we find ourselves in these situations, our reactions can overwhelm us.” (Mingyur Rinpoche 5)

He continues: “Using our inner resources to work with these issues is our only true protection, because external circumstances change all the time and are therefore not reliable.” (Mingyur Rinpoche 5) Rinpoche’s observation is essentially that we cannot control our environment; we can only control how we relate to it. Therefore, whether or not we continue to suffer ultimately depends on our own internal attitudes.

This in turn explains the centrality in Buddhism of learning how to better relate to our suffering through actual practice. Rinpoche writes: “Tibetans have a word for deliberately increasing the challenge of maintaining a steady mind: adding wood to the fire.” (Mingyur Rinpoche 5) Giving up my phone was my own way of adding wood to my fire. I was challenging myself to confront my fears: of being judged, of being alone, of being overly anxious. Instead of avoiding situations I feared—and thereby perpetuating my suffering because I couldn’t always avoid them—I would confront them directly. In doing so, I realized that the situations I feared weren’t actually that bad. Most importantly, each time I didn’t pull out my phone (since I couldn’t), but instead stayed right where I was, I was reminded that I had the capacity to deal with whatever was happening. I could decide how to respond.

It’s been more than seven weeks now since I stopped using my phone, and I don’t want it back. For one thing, giving up my phone has made me more aware of my surroundings, of other people, and of my own emotions. But more than that, it has taught me that I can choose how I relate to all of these things. Instead of relating to other people or my own emotions with fear or avoidance, I can relate to them with awareness and calm. By giving up my phone, I have decided to stop distracting myself from my own suffering—from my own life. Instead, I am choosing to relate to my life in a more constructive way. I am choosing to fully live it.

References

Sestavonich, Clare. 2021. Objects of Desire. New York: Knopf.

Mingyur Rinpoche, Yongey. 2019. In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying. New York: Random House.

Related features from BDG

The “Happy Birthday” Song

Finding Comfort in Not-Knowing

Buddhism and Self-Reliance: Learning For Growth