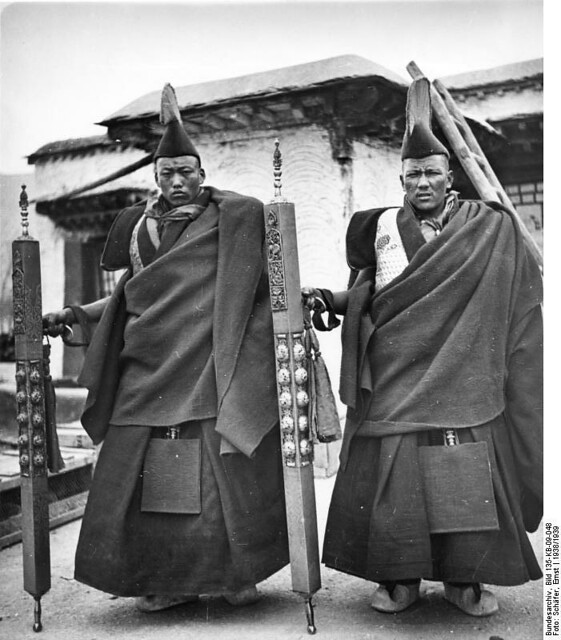

19th century. From Core of Culture

Tibetan Buddhism has garnered a reputation among many, especially in the West, for being a unified, peace-loving religion. This is remarkable considering that Tibetan history—and that means Buddhist monastic history—is one of the most bellicose and bloody anywhere. I will never forget attending what was ostensibly a performance of Buddhist arts by Tibetan monks at a university outside Chicago some years back. After each sloppily performed act, a giddy, clownish monk would amble onto the stage and cry, “World peace! Thumbs up!” He would then ask for money. Not only was the dancing bad and the pitch an embarrassment, it perpetuated this notion that Tibetan Buddhist monks have always been about world peace, and their arts an expression of that. Far from it! A clearer perception of the complex identity of Tibetan Buddhism and its arts is available.

This article is not a critique of the martial aspects of Buddhist dance—I am an admirer, archivist, and practitioner of martial movement forms. Nor is it a critique of historical sexual behaviors that are better understood through an honest attempt at contextual objectivity, rather than viewed through the lens of contemporary moral judgment. Tibetan Buddhist society was feudal and complex; its mysticism ancient and powerful, its historical identity forged in warfare. This essay intends only to challenge rose-tinted notions of Tibetan Buddhist culture that may perhaps reflect an overly idealistic “Shangri-La syndrome” common among Westerners as much as a revisionist PR campaign by Tibetan monks. Further, this column seeks to comprehend the true nature of monastic dance forms—something that in the West has no equivalent, and for which we have often substituted romantic or impotent notions.

Tibet fought its neighbors for centuries. Indeed, they were despised for it. The kingdom of Bhutan is singular among them for never having been successfully invaded by Tibet. It is also important not to label all Vajrayana Buddhism “Tibetan Buddhism.” They are not the same thing. Domestically, Tibetan monastic orders physically fought each other for political dominance. The political and religious authorities in that vast and ancient land were related by blood in most provinces, and the aristocratic genetic links within orders remain today. There was much power and wealth to protect. Tibet’s monastic culture was a pure expression of medieval feudalism. The dances and arts enhanced and facilitated the meditative practices of educated monks and provided religious expression for the uneducated masses, serving to strengthen the minds of monks and the allegiance of peasants. At the same time, Cham was also a means of physical training.

Men like to fight. To this day, the ancient martial arts of many cultures exist and thrive. The subject of Buddhist martial arts is vast, encompassing everything from the Shaolin monks, to the Samurai code of honor, to Zen archery. The martial aspect is more explicit and more alluring than the strict mental discipline: today’s martial arts culture is dominated by competitions and rankings—such as “belts”—that have no basis in history or Asia (how many of us have nieces or nephews under the age of 10 with a “black” or at least a “brown belt”?), and a kick-ass movie culture that has spanned decades. Those training in martial arts for spiritual discipline, such as the Shaolin monks historically advocated, are not unknown, but certainly rare.

Monasteries have been the exclusive domain of men. How many men need to gather before there is a fight, based on testosterone alone? One hundred? Tibetan monasteries had thousands of men; some had more than 10,000. And, as in any other exclusively male community, practices such as hazing, forced submission to sexual domination that had nothing to with sexual attraction, and training an elite group of warriors were all part of Tibetan monastic culture.

Tashi Tsering’s (1929–2014) extraordinary autobiography The Struggle for Modern Tibet details his own abuse by a martial class of monks known as dob-dobs, who were often self-appointed police and holy terrors in Gelug monasteries; described by the British political officer and noted Tibetologist, surgeon, and philosophical theologian Sir Charles Bell (1870–1945) in his Portrait of a Dalai Lama: the Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth, as “bursting with superfluous energy, spoiling for a fight.” I read Tsering’s book because he was a dancer, in fact a member of the 13th Dalai Lama’s elite group of dancing boys. I had not expected it to be full of whippings and beatings, kidnappings, and dogged pursuit by dob-dobs, who chased after the young boys for sex. The boys, in turn learned to defend themselves, banding together and hurling rocks, or, as in Tashi Tsering’s case, allowing themselves to be the passive sexual partner of a powerful monk who could often, but not always, protect them from assault. There was an abundance of raw aggression.

The elements listed here are more about what was done with the unchecked testosterone-fueled behavior that was simply a by-product of so many men living in such close proximity. The dob-dobs were permitted liberties in dress and hairstyle, and the basic monastic disciplines were not required of them—in fact, were often denied to them. It was a way of dealing with natural bellicosity. The Tibetan Buddhists had a class of warrior monks, highly skilled in Tibetan martial arts, today one of the least understood or revealed martial traditions. We know, for example, that these arts included wielding iron darts attached to ropes. Dob-dobs competed in their own style of competitions, such as boulder-hurling and jettisoning people from seesaw-like launches. It was all aimed at keeping them occupied. The dob-dobs were not dancers, the dancing boys were not monks, and they were not doing monastic Cham, but the incidents are clear indicators that fighting was commonplace.

What is the role of dance in all this? Since first seeing Buddhist Cham 20 years ago, it has been clear to me that Cham conceals a martial art just as Japanese Noh does. Its first use was to subjugate. In Bhutan, we were fortunate to see 500-year-old militia-training dances, called zhey, used to unify ragtag groups gathered to defend the country. These dances included trust exercises, as well as repeated sword strokes in the choreography, that amounted to coarse sword training.

We once brought a Japanese sword master practitioner to Bhutan who was puzzled, considering the victorious history of Bhutanese warfare, by the oddly dull and inefficient swords used by Bhutanese soldiers. We asked who taught them to use the swords. They at first replied, “Nobody.” Then, later, they hinted, “Our fathers taught us.” Only a couple years later did we learn that soldiers were trained using dance, and beyond that, dance played a part in driving up the pyrrhic frenzy needed to kill with abandon. So, in this case, there was no real sword technique. Rather there was basic sword-stroke training and unified movement taught through dance. Dance and visualization-based pyrrhic frenzy, was designed to inculcate the strategy, “rage and chop their heads off.” The Bhutanese have never been occupied and only once, by the British, defeated with a loss of low territory. There is success in Bhutanese martial history. What country has not been occupied?

The pyrrhic nature of the dances used in warfare—even as late as the early part of the 21st century—was contained within the Cham dances of protective deities. Cham dances were deployed as part of the black magic wielded against enemies, and used to strike terror into the hearts of invaders. Cham was also frequently used as a subterfuge, with dancers creating distractions, and in some cases, concealing weapons. In one famous example, Bhutanese monks bearing weapons in deity garb and masks exited a monastery just as the Tibetans were ready to invade. The cunning was that the monks simply encircled the monastery and exited it again, making it seem like an enormous army. But more than that, at the same time the Tibetans thought the Bhutanese were insane with ferocity and therefore dangerous, and the invasion was abandoned.

Whether exemplified by Guru Rinpoche’s establishment of Tantric Buddhism in Tibet by means of subjugating local deities, Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje’s murder of the apostate King Langdarma in 842, establishing the second flourishing of Buddhism in Tibet, or the flaming sword of Manjushri cutting away illusion and ignorance, victory and defeat are common tropes in Buddhist tantric history. This article introduces in broad strokes some ways that martial behavior has qualified Buddhist dance in Vajrayana Buddhist culture. Future articles will look at the dance itself more closely, and how it conceals a martial art while bringing to life the terrifying nature of protective deities.

Vajrayana localities. Photo by William Trimble