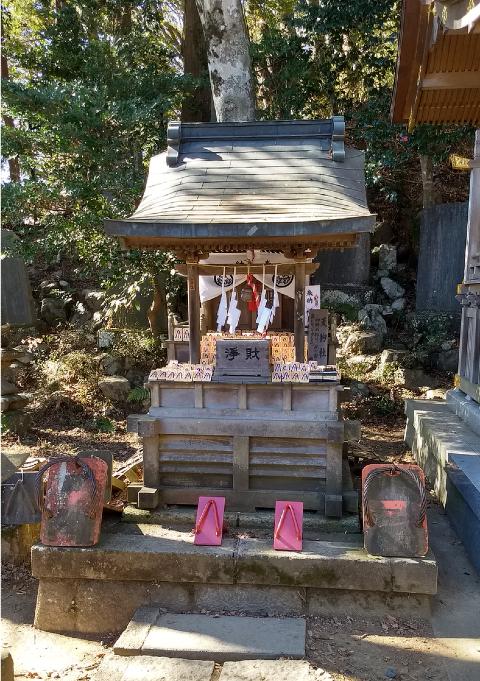

In many forms of Japanese Buddhism as well as in Shintō, a great emphasis is placed on words. In Shintō, words are what defile us and what purify us. At the entrance to most shrines, one can find a “water basin” (Jap: temizuya) where people wash their hands, mouths, and, sometimes, foreheads to purify themselves. The same emphasis on purifying body, speech, and mind, can be found in Shingon Buddhism, aptly called “true word” Buddhism. Body, speech, and mind are referred to as the “three mysteries” (Jap: sanmitsu) that open the gate to Buddhahood. But other forms of Buddhism in Japan value linguistic expressions as well. The evocation of Amida Buddha with the phrase “namu amida butsu” or the evocation of the Lotus Sūtra with the phrase “namu myōhō rengekyō” constitute the primary religious practice of the various forms of Pure Land and Nichiren Buddhism, respectively. Finally, in Zen Buddhist texts, masters verify the spiritual state of their disciples with exchanges that are rarely devoid of linguistic expressions.

The evocations in Shintō, called norito, and the mantras in Shingon Buddhism are not to be used in scholarly or intellectual discourse but rather are used for their spiritual power. The word “soul of words” (Jap: kotodama), a Japanese phrase often used in the Shintō context, suggests that words themselves have spiritual power/s. It is not only our hearts that can be pure or corrupt, our words have equal power. They can lift people up or they can destroy; they can calm someone down or they can rile someone up; they can inspire hope or they can cast desperation. At one point or another during the day, each of us is guilty of using words that cause suffering, engender hatred, and even crush somebody’s spirit. This is why Japanese wash their mouths before they enter a Shintō shrine and some Buddhist temples: our words reveal our hearts.

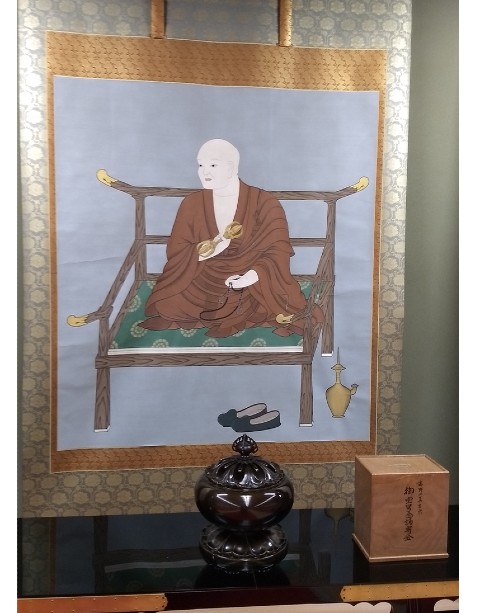

on Mt. Kōya. Photo by Gereon Kopf

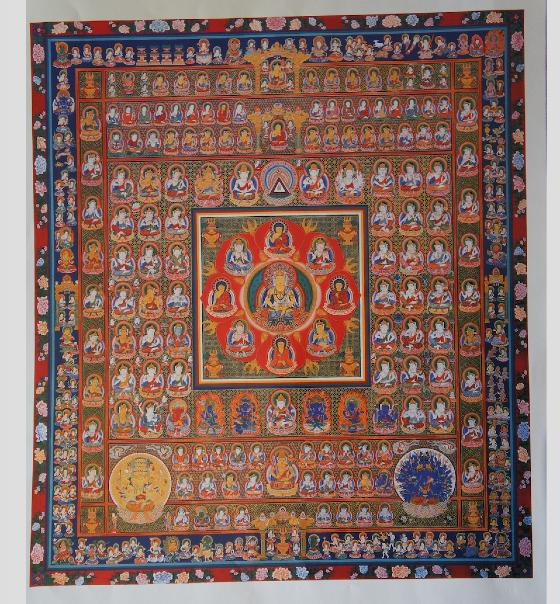

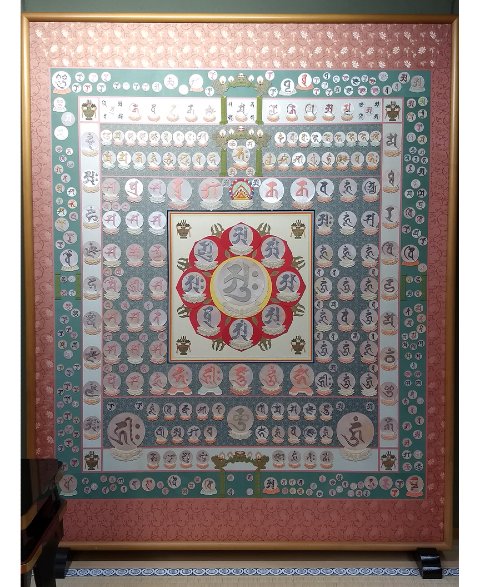

In Shintō and Shingon Buddhism, liturgic phrases purify because of their inherent spiritual power. Norito bring us in tune with the kami, the divine presence as conceived in Shintō, while the Shingon mantra constitutes nothing less than the speech of the Buddha. The founder of Shingon Buddhism, Kūkai, proposed that “if a Shingon practitioner observes this principle, and . . . chants mantras with the mouth . . . the three mysteries will unite in mysterious empowerment and the practitioner will quickly reach a state of great attainment.” (Kūkai 2011, 61) Mantras, “true words,” comprise one of three practices to embody the Buddha and to “become a buddha in this very body” (Jap: sokushin jōbutsu). Divine words and phrases bring about purification and sanctification. By the same token, as Zen master Dōgen would add, “The World-honored One uses secret words, secret actions, secret manifestations” (DZZ 1:394) to correct “false views” (Skt: dṛṣṭi-vipatti, Jap. mōken) and “false speech” (Jap: mōgo).

So far so good: there are divine words that heal and sanctify, while other words constitute means of corruption and destruction. To find out why some words heal and others hurt we need to turn to a Buddhist philosophy of language. One of the early key texts that analyze the way language works is the Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā-prajñāpāramitā-sūtra). This text boldly claims that “the notion of self is not a notion; the notion of person, the notion of a sentient being, and the notion of lifespan are also not notions;” (T 235.8.752b18–20) “the so-called Buddhadharma is not the Buddhadharma. (T 235.08.749b25) In these passages, the Diamond Sūtra postulates a gap between names and reality, words and meaning, “signifier” (French: significant) and “signified” (French: signifié). Similarly, Dōgen describes this dissonance between words and meaning as follows: “At one time, there is meaning but no words; at one time there are words but no meaning; at one time, there are both meaning and words; at one time there are neither meaning nor words.” (DZZ 1: 193)

But neither the Diamond Sūtra nor Dōgen conclude that we have to give up the use of language. The Diamond Sūtra attributes immense value to concepts and language. It observes that “what is sometimes referred to as ‘all dharmas’ are not all dharmas, therefore they are called ‘all dharmas.’” (T 235.08.751b02–04) Dōgen responds to the famous Flower Sermon, in which the Buddha explained the meaning of holding up a flower on Vulture Peak by saying, “I have the eye treasury of the true Dharma. . . . It does not depend on letters and words,” (T 48.2005.293) with the sarcastic observation that “if The-World-honored One had hated using words but loved picking up flowers, he should have picked up a flower at the latter time (instead of giving an explanation) too.” (DZZ 1: 394)

In all those passages we can see that, to the Diamond Sūtra and Dōgen, linguistic expressions are important not only to purify corruption but also to communicate the teaching of the Buddha. Yet if there is a gap between phrases and meaning, how can we ascertain which phrases cause hurt and which phrases heal. For this, we need to look to one more of Dōgen’s writings. In his fascicle Shōbōgenzō dōtoku, Dōgen rolls out what can be understood as his philosophy of language:

All Buddhas and all ancestors constitute expression. For this reason, when ancestors select ancestors, they ask whether or not they can express themselves. . . . When we express expression we do not express non-expression. Even when we recognize expression in expression, if we do not verify the depth of non-expression as the depth of non-expression, we are neither in the face of the buddha-ancestors nor in the bones and marrow of the buddha-ancestors. . . . In me, there is expression and non-expression. In him there is expression and non-expression. In the way there is self and other and in the non-way, there is self and other. (DZZ 1: 301–5)

As mentioned above, in the Zen canon, teachers confirm the attainment of their disciples by means of linguistic expressions. However, the words we choose are incomplete; if we are not aware of this, we will set up boundaries. When we set boundaries, we distance ourselves from all buddha-ancestors. We will deny what our words do not express, we will ignore the walls we erect between us and them, between self and other. However, when our words, phrases, ideologies, and practices are inclusive, we purify ourselves and embody the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha. In other words, only when we are aware of the non-expression in our words, only when we listen to the expressions of all others will we become whole, will we be able to heal the wounds that persons, communities, and ideologies inflict. Only then will we become buddhas in this present body.

References

Dōgen zenji zenshū (Complete Works of Zen Master Dōgen). Two volumes. Edited by Dōshū Ōkubo. 1969–70. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. [Abbr. DZZ].

Kūkai. 2011. “Realizing Buddhahood.” Trans. David Gardener. In Japanese Philosophy A Sourcebook, eds. James Heisg, Thomas Kasulis, John Maraldo. 59–61. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Takakusu, Junjirō and Kaigyoku Watanabe, eds. 1961. Taishō taizōkyō (The Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon). Tokyo: Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai. [Abbr. T].