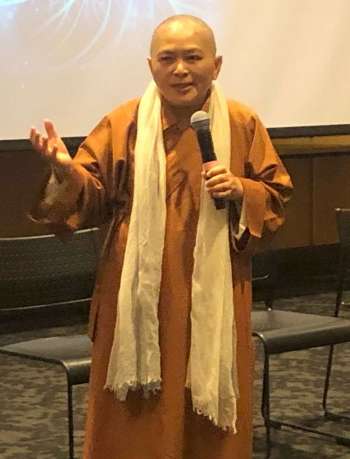

In 2017, Venerable Dr. Yifa, founder of the Woodenfish Foundation, an international, non-sectarian NGO, started what has now become an annual conference under the theme “Buddhism, Science, and Future.”After holding two successful iterations in China, the most recent the event was hosted in the United States at the University of Washington, Seattle earlier this month. In her opening speech before an audience of some 150 attendees, Ven. Yifa evoked Yuval Noah Harari’s famous declaration that “consciousness” is the biggest unknown of the 21st Century. While highlighting the fact that Buddhism has been investigating consciousness since time immemorial, Ven. Yifa was seconded by other speakers in her assertion that the present moment is forcing us to look at this subject anew.

If you are anything like me, when you hear the words future and artificial intelligence (AI), you may worry about the inevitability of human-like robots taking over the world. Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for AI, addressed this common concern at the beginning of the conference, stating: “What is called machine learning is 99 per cent human work today, and for the foreseeable future.” So while the computer program Alpha Go was able to beat professional chess player Lee Sedol, in order to make this happen a human being had to push the button. Furthermore, Alpha Go may be very good at chess, but Etzioni assured us that—like all other AI—the program is extremely good at a very specific task, and nothing else.

This view was echoed by 23-year-old Yuhan Guo Frost, a student at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, who posited that we are a far cry from seeing the type of robots depicted in Hollywood sci-fi movies. Speaking as part of the Youth Science Symposium, Frost shared his experiences with regard to often-misguided perceptions of technology.

Photo by Nina Müller

During a public showing of his senior project—a tool that prevents credit card information from being leaked to databases—he was surprised to see that a large portion of those questioned described the project as “scary.” Enquiring why such feelings arose in the face of a technology that is supposed to protect user data, Frost realized that buzzwords such as “data leakage” and “large corperations” were catalysts for this unfounded fear. He expressed hope that the future would enable us to “help fill this gap of knowledge in the technology field.”

Instead of a world full of human-like robots, James Hugh, executive director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, told Buddhistdoor Global that technological advances will more likely result in the enhancement of human beings. Indeed, among the various technologies discussed during the conference, a number are aimed at improving neurological pathways in the brain to achieve beneficial effects similar to meditation. The Muse, a device worn by a member of the audience throughout the conference, allows individuals to receive direct feedback on the state of their brain.

Wayde Silby, representing Calvert Investments and Social Venture Network, highlighted the effectiveness of transcranial magnetic stimulation, a treatment that reportedly has a 60 per cent success rate in curing depression, and noted that technologies are being developed to treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as helping to create “aha moments” of insight without the need of spending years on the meditation cushion.

Among other technology frontiers that were discussed was genetic engineering, which could enable parents to select embryos that are healthy, intelligent, and good-looking.

Not all speakers were on board with this idea, however: Bonnie Duran, a professor at the University of Washington, who guided us through a wonderful Earth meditation, argued against “fixing disabilities.” Instead she advocated that we as a society learn to “accept humans in all their diversity, no matter what our bodies look like.”

Another controversial topic was the notion of prolonging human life. While Hughes acknowledged that Buddhism teaches us about the inevitability of sickness, aging, and death, he stated that this should not be a reason to stop looking for treatments for these ailments—joking that he is in favor of such measures because it may very well take him 1,000 years to attain nirvana.

Buddhistdoor Global also caught up with Buddhist chaplain and end-of-life caregiver Breeshia Wade, who shared her views on life and death: “I honestly think that death is a beautiful thing and I thank God for it. I can understand the urge to want to control how we die—we want to die with a sense of dignity and to minimize any pain. And I can definitely understand the desire to prolong life in instances where someone is young and dying too soon. I think that death gives life meaning, and I’m not saying that we couldn’t find any other form of meaning outside of death, but I think that having to come into contact with our deepest fear and having it be inevitable—not having control—gives us incentives to attempt to live life more intentionally.”

Despite some controversy, a number of speakers agreed that when it comes to technology, nuclear weapons are the biggest threat to life on earth. The overall consensus was that technology is a tool that should be developed and used ethically.

Hughes, Duran, and Etzioni all warned of the self-serving, capitalistic drive toward technological advancement. Hughes advocated technologies that are equally accessible to all while Duran compelled us to look at our motivations. “There is nothing inherently evil about technology,” she said. “We need to look at what our intentions are when developing our projects. They have to be based on generosity and universal love.” How can we do this? My favorite suggestion came from Ying Yao, a 23-year-old student of psychology and philosophy, who urged us to “build our ethical values into AI, into coding.”

As Ven. Yifa closed the conference, she smiled at the fact that we had not come to a conclusion, explaining that she hoped that this would be the beginning of an ongoing discussion about the future of Buddhism and science.

Woodenfish Foundation plans to organize further conferences on the topic in Shenzhen in August 2019, and in Boston in 2020.

See more