It is the day before a full moon and the temple at the village of Hson Kae in Hsipaw Township in eastern Myanmar’s Shan State is abuzz with activity as scores of people arrive on foot, bicycles, motorcycles, and bullock carts from surrounding villages. Dressed in their best clothes, Kham and his family make their way through the crowd to the hall. Kham has been looking forward to this day for months, for today he will pay off the last installment of a loan from Wong Metta Saving and Credit Union.

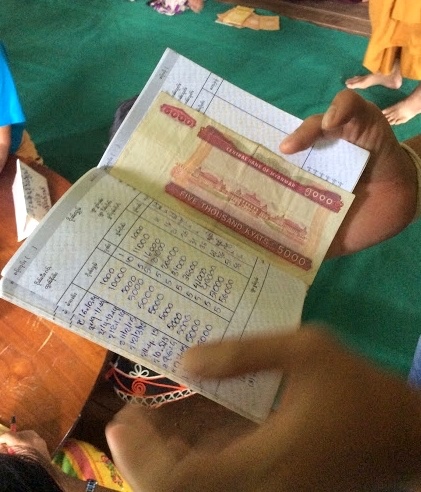

Inside the hall, credit union volunteers sit around low tables, busily placing money in the large silver bowl on the table and adding entries to ledgers as villagers carrying little savings books wait patiently. When his turn comes, Kham hands his money to a volunteer, who makes a corresponding record in his loan book in the local Shan language. With the paperwork completed, Kham heaves a sigh of relief and offers a broad grin: “Now I feel rich because I am debt-free. And I still have some savings to send my two children to school.”

Two years ago, Kham would not have thought this could be possible. Faced with a failed harvest due to bad weather, he was at wit’s end as to how to feed his family of seven. Fortunately, he was able to secure a loan from Wong Metta that helped to tide him over the difficult times and buy seeds for a new crop. Today, with his income stabilized and with a good harvest, he has managed to repay his loan within a year and still have some savings.

Founded by a group of lay Buddhists and monastics in Shan State in 2008, Wong Metta is the most extensive temple-based savings-and-loan scheme in Myanmar. It has more than 140,000 members in 400 credit unions located in temples primarily in Shan State, with a few in Mandalay Region, Bago Region, and Kachin State. In a country where less than 20 per cent of the population have direct access to formal banking services, temple-based credit unions such as Wong Metta offer an invaluable alternative for poor rural villagers, most of whom have little or no understanding of the financial world.

Co-founder Sai explains: “Two-thirds of Myanmar’s population live in 70,560 rural villages, many of which are still very undeveloped. Many live at a subsistence level, on a day-to-day basis. Most have no savings, and even if they have a little, they keep it at home and soon spend it. When they are in dire straits they may go to local moneylenders, who exploit them by charging high interest rates. They have little knowledge of accounting or banking. Furthermore, going to a bank may take one or two days of travel, and there is so much paperwork involved that it scares off the poor farmer. There is also a degree of distrust. By basing the credit union in the village temple, we make it accessible to the rural population. We educate them about the importance of saving. As most people are Buddhists, we use the Buddhist teachings to encourage them to save a small part of their meager income. For example, in the Sigalovada Sutta, householders are advised to divide their wealth into four equal divisions, the last of which goes into savings for times of need. Saving with Wong Metta, even at lower interest rates, is more reassuring than saving with unknown entities.”

Image courtesy of Proxmity Designs

According to Sai, Wong Metta is one of the leading micro-finance institutions in Myanmar in terms of providing financial services to the largest number of people. In the village of Hson Kae, for example, more than 90 per cent of the residents are members of the local credit union.

The main criterion for membership is that one must live in the area. Each member is expected to save 1,000–30,000 kyat per month (US$1–30), depending on an individual’s capacity. Deposits and borrowing are conducted once a month, usually on the day before a full moon, when members are expected to bring their savings together with their membership booklet to the temple. Those who fail to attend the monthly gathering are fined and the fines put into a common fund.

transactions. Photo by K. V. Soon

Local volunteers and a selected committee man the credit unions at each temple. The day begins with the depositing of savings and the collection of loan repayments. By about midday, the total amount collected is handed to the committee, which is responsible for deciding whom to dispense loans to, according to the rules and regulations. Only those aged 18 and above are eligible to apply for loans. In cases where there is more than one member in a household, no member can apply for a new loan if there is an outstanding loan in the same household. This is to prevent households from incurring too many debts.

The priorities for lending are set according to the borrower’s needs. The first consideration goes to those who need money for medical treatment. Next are loans for the repayment of debts from other sources, such as loan sharks. Then come loans for physical necessities, such as food and shelter. This is followed by those for children’s educational needs, and finally for capital investment for small businesses. One strict rule is applied for all borrowings—it cannot be lent to someone providing loan shark services.

Loan amounts range from 100,000–10 million kyat (US$100–10,000). Various criteria are taken into consideration: the amount available, the credit-worthiness of the borrower, how long and how much the borrower has saved, their family background, and how long they have lived in the area. Existing savers may borrow up to 10 times the amount in their union account, but for every loan, there must be at least two guarantors who are also members of the union.

Repayment is planned in accordance with the borrower’s capacity. This consists of monthly installments plus interest, which starts at 4 per cent monthly, falling to 2 per cent when the union has operated for 3–4 years. For small-scale enterprises and poor farmers, this low interest rate enables them to grow their businesses without resorting to expensive, unregulated credit with exorbitant interest rates as high as 10–15 per cent, which often not only wipes out any profit potential, but relegates the borrower to an endless cycle of debt.

low interest rates for loans for capital

to expand. Photo courtesy of Proxmity

Designs

The credit union holds no reserves. After the day’s deposits and loans are accounted for, any excess is kept at a commercial bank. One year after the setting up of the credit union, all the interest gained is divided into two equal amounts. Half is distributed as a dividend to all the members, according to their level of savings, and half is set aside at the temple as a welfare or community fund for emergencies and financial hardships, such as childbirth, death, sickness, and old-age.

The affiliation of Wong Metta with the local temple carries significant implications. The system is underpinned by Buddhist morality and fundamentals. In a culture where graft and corruption are not unfamiliar, Wong Metta is highly creditable for its transparency. The entire savings-and-loan process is conducted in the presence of the members, which provides a social impetus for all involved to fulfill their obligations. The presence of a head monk reinforces the sense of responsibility and trust in the system.

The process of lending is highly ritualistic, beginning with borrowers observing the Five Precepts and chanting led by the head monk. Borrowers swear an oath to profess the true reason for the loan and their sincere intention of paying back. The money collected in the bowls is presented as an offering to the Buddha, rendering it “Buddha’s money.” Stealing Buddha’s money can have grave consequences! If the borrower repays the loan, they will prosper; if they don’t, their business will be ruined. Borrowers believe that if they fail to repay the loan in this lifetime, they will have a less favorable rebirth. Hence, although no physical collateral such as land is required for lending, a more potent and intangible collateral exists—the well-being of the borrower, both in this life and the next. Perhaps this is why, despite the absence of any central control across the 400 Wong Metta Credit Unions, the total default rate is estimated at less than 2 per cent.

More significantly, Wong Metta upholds the traditional role of the temple as the heart of the village in a country where, for centuries past, Buddhism has been a defining aspect of the culture and the way of life, and where community, compassion, and faith work together effectively for peace and harmony. Wong Metta’s faith- and community-based approach allows members to manifest the Buddhist ideals of mutual care and loving-kindness in a very concrete way by allowing their collective savings to be transformed into financial assistance for those in need within the community. As Kham observes: “When we save with the bank, the money goes elsewhere. If we save with the credit union, the money benefits the community. Instead of getting help from outside, we are helping ourselves and our community.”

See more

Afford TWO, Eat ONE, Financial Inclusion in Rural Myanmar (Proximity Designs)