Here Anju prepares offerings before the Tenmu Tenno shrine whose doors are open only for the short

duration of this celebration. Image courtesy of Sakuramotobou

In 2015, rare medieval documents discovered inside fusuma wooden doors took academics by surprise. These fusuma were originally from Sakuramotobou, one of five “guardian” temples of Ominesan-ji, the temple and sanctuary on Sanjogadake Peak in the Omine mountain range. The ancient documents had been stuffed into the fusuma for insulation purposes. A professor of East Asian studies and a librarian of Princeton University purchased these documents with the aim of securing the materials for study and transcription by students. Little did they know then that they had purchased a rare treasure!

Of the 119 documents, almost half were written between 1308 and 1615, and the remainder were written between 1615 and the late 17th century. The earliest document even predates Sakuramotobou’s official records. Many of the temple’s old records had been lost during the Meiji period, when the Japanese government split Shintoism and Buddhism, and prohibited Shugendo.

Please find the Princeton University press release about the discovery here. Thorough research is still under way, but the preliminary findings are these:

Many documents were addressed to the Sakuramotobou temple itself or to individuals affiliated with the temple. Sixteen documents relate to the activities of visiting Yoshino Mountain, such as tour fees and lodging arrangements, which show the relationships between Yoshino Shugendo, worshippers, guides and tours . . . many documents were written by women. . . .

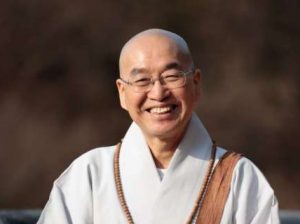

In this article, the author continues her conversation with Tatsumi Anju about Sakuramotobou’s role in history, her role at the temple, and about the advancement of women in Shugendo. Click here to read the first part of this interview.

The author is very grateful for this interview and would like to thank Tatsumi Anju for her frank and heartfelt answers.

BDG: Could you please tell us a little about the early history of Sakuramotobou?

Tatsumi Anju: The history of Sakuramotobou began with the dream of a cherry tree by Prince Oama, who later became Emperor Tenmu (631–86 CE). This was in the year 671, when the older brother of Oama, Emperor Tenji, governed the nation, while Prince Oama stayed at the Yoshino Imperial Villa.

One very cold night Oama had a dream of a single cherry tree in full bloom during snowy mid-winter. The next morning, finding this dream was very meaningful, he asked a priest, Kakujo, a disciple of Shugendo’s founder, En no Gyoja, to interpret it.

“A cherry blossom represents the Japanese floral emblem, which is an auspicious sign of you ascending the throne,” the priest is said to have answered. In the following year, Oama was victorious in the Jinshin Revolt, which resulted in him succeeding to the throne as Emperor Tenmu.

Returning to Yoshino, the new emperor found the exact cherry tree he had seen in his dream. He built Sakuramotobou—literally “temple built close to the cherry tree of which Prince Oama dreamed”—and he designated Kakujo as the chief priest.

Since then, Sakuramotobou has been maintained in its history and prayers in the style of the syncretism of Shintoism, Buddhism, and Shugendo for some 1,350 years.

A group of gyoja related to Sakuramotobou observe the ritual, which is conducted in Shinto style by Anju.

Image courtesy of Sakuramotobou

BDG: What is your family’s role in the history of this temple?

TA: My family, the Tatsumis, have been taking care of Sakuramotobou as head priests for more than four generations. These were my ancestors: Ryoshin followed by Ryokai, then my grandfather Ryojo, and now my father Ryonin.

The priest before Ryoshin went through the extremely difficult time for Shugendo temples during the Meiji Restoration. At that time, Sakuramotobou, its buildings and halls, were attacked and severely damaged. Many important documents and items were burned or stolen. After that, there was no priest and nobody else to take care of the temple for 10 years until my ancestor, Ryoshin, took over.

BDG: How was Sakuramotobou revived?

TA: Ryoshin had to start from scratch after this empty, lost, and blank period of 10 years. There was almost nothing left of the temple’s former belongings, such as ritual books and implements and statues of deities. He had to search for and gather together what Sakuramotobou once held.

We are still struggling with these scars from the Meiji Restoration till now, and we are still searching for items that belong here. My family continues to revive this temple to the best of our ability. For example, the original statue of Tenmu Tenno, the founder of the temple, was stolen and we know that it is now somewhere overseas. Luckily, the Tokyo National Museum had a sketch of this statue so that we could commission a new one in the 1990s.

Many people have been helping my family, including gyoja, members of the Yoshino Shugendo communities, and other locals and priests, both Buddhist and Shinto, as well as researchers like those now at Princeton University.

BDG: How did the Shugendo practices survive the chaos of the Meiji Restoration?

TA: The saddest thing for Sakuramotobou was the fact that there was no one left who could pass on the rich history of the temple to the next generation. Luckily, the core of Shugendo and the essence of the prayers was somehow kept alive in the wider Yoshino area.

Since Shugendo prayers contain both Buddhist and Shinto elements, the tradition had become a main target of the Meiji government. The official stance was that Buddhism and Shintoism had to be separated and Shugendo, considered backward, was abolished.

This was an extremely difficult time for all followers of Shugendo and for all Shugendo places, including the main sanctuary, Ominesan-ji on Sanjogadake Peak. Interestingly, this Shugendo sanctuary was turned into a shrine and in this way it could be protected. For 10 years, a Shinto priest took care of what was Ominesan-ji.

The followers of Shugendo continued their practices in nature and worshipped at Ominesan-ji as a shrine then. In this way, Shugendo practices were carried on with what followers had, and in the way that they could, until Shugendo practice became legal once again and practicing was allowed.

observers rather than participants as they would be at other ceremonies at this Shugendo temple.

Image courtesy of Sakuramotobou

BDG: How do you contribute to continuing the legacy of Sakuramotobou?

TA: From this year, I am in charge of holding monthly seminars for anyone who wants to learn about the spirituality of Japan through the lens of Shugendo. With this we are targeting women and young people, such as students and even children.

By this I mean that there was no concept of Shugendo as being syncretic or being a combination of Buddhism and Shintoism before the Meiji Restoration because prayers were unified, containing elements from both religious traditions and other influences too. This was the natural way to pray for Japanese people.

The division that happened during the Meiji Restoration was artificial and people today simply do not know about the old ways. Children are not taught about Japanese spirituality at school and often they do not live with their grandparents who still remember the old ways.

We want to let people know that this temple is here for all people! I often hear people say that they cannot come here because they feel that a Shugendo temple is only for gyoja and only for men. This is not true! Anyone can come to us! In this sense I believe that these seminars are also a place for counseling, offering prayer as one option for mental healthcare.

BDG: I dare to pose this question again: will you become the head of Sakuramotobou in the future?

TA: My brother Ryodo passed away from cancer and I am the only child now. However, the succession has not yet been decided.

In the history of Sakuramotobou, the hereditary system of passing the temple on has continued “on and off”. Depending on the era and on events at the time, the temple was passed on within a family for generations, but then a disciple priest without blood ties could also inherit the temple and become the head priest. It seems that sometimes there was no other choice because of the circumstances and conditions.

Today, there is absolutely no rule that the children of the head priest have to take over the position. Blood ties do not matter now. If there is a priest with passion and the appropriate skills who wants to, and who is able to take care of Sakuramotobou, then this could be a good candidate.

We think that on top of everything the deities’ choice matters the most. It is the deities at Sakuramotobou who take the ultimate decision and give “permission” to the appropriate candidate.

Drinking sake during Shinto rituals is for purification as well as to establish a bond between people and the deities.

Image courtesy of Sakuramotobou

BDG: How would such a candidate be found and trained?

TA: Our big project since 2021 has been to re-educate gyoja. We regularly hold seminars at Sakuramotobou to help gyoja relearn the true spirit of Shugendo, both from a theoretical point of view and also in terms of practice.

My father is leading these seminars but I help him prepare and facilitate the sessions, especially the sharing circles. We mainly target younger gyoja, but some sendatsu leaders and experienced gyoja are also deeply involved. We appreciate their experiences and their understanding very much.

Part of this process is the standardization of systems and rules. Some gyoja have become arrogant, and act and behave as if they are “the king of the world.” They conduct rituals, including the goma fire ceremony, in their own way and do not follow what they were taught during initiations such as tokudo and denju. In this way, they twist the practices and neutralize the spells and ultimately ruin the ritual. Young and innocent gyoja think these sendatsu leaders are doing the right thing and they start copying these bad habits. We want to stop this negative loop with our seminars.

Some gyoja make this project sound too dramatic and controversial. Some others do not want to change but prefer to stay in their comfortable position where they can be bossy. There are also those who do not want to accept that a woman could become the head of Sakuramotobou and thereby the leader of a Shugendo temple. These gyoja are not happy that I am taking part in this project. Some told me directly that there was no future for our temple because I am a woman. I will not stop communicating with any gyoja because of this.

Whatever the choice will be, I sincerely hope that Sakuramotobou will be a young-gyoja-friendly, independent-gyoja-friendly, and women-gyoja-friendly temple! In this way, I will continue promoting Sakuramotobou to let everyone in the world know that we provide access to Shugendo learning and that we support those who come to develop and grow, not only as a gyoja but also as a human being.

See more

Related features from BDG

Women in Shugendo: Supporters, Leaders, or Both? Part 1

Women in Shugendo: Supporters, Leaders, or Both? Part 2