Editor’s note: This is the third part of a three-part essay recounting a 20 July protest by American Buddhists at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, where plans were underway to expand facilities holding detained immigrants. You can read the first part of this essay by Buddhist scholar and Soto Zen priest Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams here: At Fort Sill, a Prayer That History Would Not Repeat Itself (Tricycle), and part two here: What American Buddhism Looks Like: Solidarity for Immigrants at Fort Sill (Buddhistdoor Global).

On Independence Day—4 July 2019—I began circulating a letter inviting Buddhist clergy and lay leaders to join me in supporting Tsuru for Solidarity, a Japanese American group dedicated to the idea that American concentration camps used to incarcerate children and families in World War Two were wrong then and similar camps for Central American children detained at the US border are wrong now. By the day of the 20 July Fort Sill protest, about 130 Buddhist leaders had publicly signed on to express their solidarity, and dozens of temples and organizations began folding paper cranes. Tsuru for Solidarity initially called on the Japanese American community to fold 10,000 paper cranes (tsuru is the Japanese word for crane, a symbol of hope and transformation in Japanese culture) for their first protest in March 2019 at Dilley, Texas, where thousands of children and some women seeking legal asylum are being detained indefinitely by the US government.

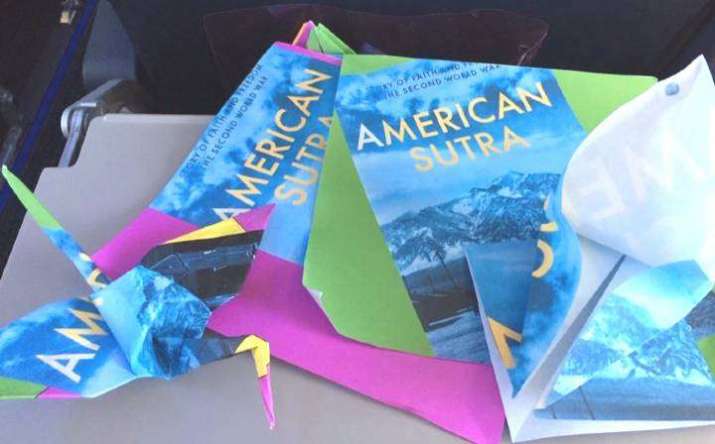

The community responded with some 25,000 folded cranes, to be taken on a pilgrimage to Crystal City, a former World War Two concentration camp that housed Japanese American and Japanese Latin American families, then to the detention facility in Dilley, Texas, just a few miles down the road. Among the cranes placed on the fence were those made by Tsuru for Solidarity co-founder Nancy Ukai, who had, unbeknownst to me, made cranes using color copies of the cover of my book about Buddhism and the World War Two Japanese American incarceration American Sutra.

The current US administration’s immigration policies that target and exclude people because of racial or religious animus is all too familiar to the Japanese American community. They experienced a nationwide roundup of thousands of community leaders after the attack on Pearl Harbor during World War Two, including hundreds of Buddhist priests, based on claims that they represented a threat to national security. Ultimately, even Japanese American babies and orphaned children were forcibly removed by the US Army and placed in remote camps surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. The mass incarceration of 120,000 people was a form of ethnic cleansing of the West Coast, which, according to Lt. Gen. John DeWitt in his 1943 Final Report, was necessary because of the community’s race, religion, and customs.

So it was no surprise that when the administration of US president Donald Trump announced that 1,400 unaccompanied migrant children in overcrowded border facilities would be transferred to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Tsuru for Solidarity swiftly organized another crane-making project for a protest on 22 June. A group of 25 Japanese Americans, including six camp survivors who were children during World War Two, took a stand to express their concern about history repeating itself. When an angry military police officer interrupted the camp survivors at Fort Sill’s entrance and told them they could not protest in front of the base, one of the survivors—Satsuki Ina, another co-founder of Tsuru for Solidarity—remarked, “They’re wanting to remove us. We’ve been removed too many times.”

The camp survivors stood their ground, ready to be arrested if necessary, until they had finished speaking about the connections between the inhumane exclusions and incarcerations that they had experienced and what is happening today. Standing with thousands of paper cranes made by fellow Japanese Americans from around the country, this small group of protestors was representing a much larger community.

American camp survivors. From latimes.com

On 22 June, I was privileged to be at Fort Sill with these brave camp survivors and other descendants of families who had been incarcerated. I was invited to perform a Buddhist service at the rally in a nearby park after the camp survivors’ statements at the Army base entrance. Here, a couple hundred local Oklahomans from many backgrounds—including immigrant rights organizations, the American Indian Movement, Black Lives Matter, ACLU Oklahoma, and others in a diverse coalition—assembled to amplify their voices to stand with the incarcerated children seeking asylum and refuge in our nation.

At the rally, I posed a question, a Buddhist koan, “How do folded paper cranes fly?” What can paper cranes do to alleviate the suffering endured by so many? One of the classic Buddhist symbols of liberation is likened to a bird soaring freely in the sky. We say that for a bird to fly, it needs both wings: the wing of wisdom and the wing of compassion. What I witnessed at the rally was the embodiment of all the elements necessary to make paper cranes fly.

At the 20 July protest, a more complete answer to the question came. As part of the memorial service, a ceremonial hanging of the paper cranes on a rope held by Tsuru for Solidarity NYC members and Dreamers took place during the chanting. Some of these cranes were from the previous protest and made by Japanese Americans, but the bulk of the cranes came from Buddhist sanghas around the country. Children at Dharma camp in Portland, Oregon; Japanese American seniors at Kona Daifukuji temple in Hawaiʻi; Zen practitioners from San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Brooklyn; and countless other cities made over 4,000 cranes for this occasion.

Each fold, an expression of concern for the migrant children, is a prayer for freedom. The Tsuru team and the Buddhist clergy was a combined group of only 30 people, but in reality, thousands were present in the form of paper cranes. At the conclusion of the rally, Tsuru for Solidarity decided to gift these paper cranes to the primary organizers of the 20 July Fort Sill protest: the young Dreamers adopted the paper cranes with plans to take them to all of their future protests at migrant detention centers around the US. Paper cranes will indeed fly.

Photo by Evan Kodani

Postscript:

On 24 July, US Senator Jim Inhofe’s (Republican, Oklahoma) office relayed to the media that plans to transfer the migrant children to Fort Sill in the summer of 2019 have been put on hold. On 26 July, the White House contacted Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt about the change in plans, with the US Department of Health and Human Services announcing that their “UAC (Unaccompanied Alien Children) Program does not have an immediate need to place children in (holding) facilities.”

One camp closed. There is still work to be done. Cranes to be folded. Compassionate words to be spoken to turn the destiny of America as a nation. Fellow American Buddhists, this is but one approach to fulfilling our bodhisattva vows—“Sentient beings are numberless, yet I vow to save them all”—though if this style of engagement with the suffering of the world proposed by Tsuru for Solidarity appeals to you, they are awaiting your support. Our next goal is to fold more than 120,000 cranes to represent the number of Japanese Americans incarcerated in concentration camps during World War Two. Our next protest will be at the White House in Washington, DC, in May 2020.

Watch for updates at A Call for Buddhist Leaders to Protest Inhumane Treatment of Migrant Children (Duncan Ryuken Williams)

See more

A Call for Buddhist Leaders to Protest Inhumane Treatment of Migrant Children – Lending Our Support to Tsuru for Solidarity (Duncan Ryuken Williams)

Tsuru for Solidarity (Facebook)

Buddhist Protest of Inhumane Treatment of Migrant Children (YouTube)