Once, when I lived in Copacabana, Brazil, I had a friend living nearby. He insisted that following a spiritual path was a luxury, while I asserted that it was a necessity. His point of view was that most people can only focus on basic survival needs. I felt that without a higher context or purpose, there is not as much meaning or positive drive for the heart’s motivation to survive. Certainly, in Rio de Janeiro, as in many parts of the world, there is a wide and sharp disparity between the haves and have-nots, made viscerally evident by the hilltop favela communities and the beachfront luxury apartment buildings. I witnessed regular police corruption and the brutal harassment of street-goers due to economic and racial profiling. Not everyone has the leisure to pursue meditation or spiritual practice outwardly, or perhaps the stability and calm inwardly.

Decades later, however, I maintain my original perspective. I acknowledge that having the time and resources to engage in spiritual practice may be a privilege that not everyone has. Sometimes people’s very minds are dominated by others or by the work they must perform, or perhaps by conditions such as depression or anxiety that curtail their ability to let their mind open to spiritual practice or meditation. But my teachers and their teachers were sometimes persecuted, exiled, imprisoned, and even tortured. These people were already very great meditators when these hardships befell them, but they were able, through their strength of mind, to persevere in compassion practice even under the harshest circumstances. So I maintain that those of us who live with far fewer restrictions or violent conditions can find the space mentally—even if we work long hours or have complicated lives—to open ourselves to the possibility of communication with the unseen world for our support and benefits.

Some of these practices may be geared toward prayer and visualization for the reduction of the suffering of all beings, especially those who endure the hardships of discrimination and related acts of violence—whether due to race, gender, creed, size, shape, age, origin, or ability. For those who have already cultivated some meditation practice or spiritual path, there is often an engaged component, especially for those living in cultures that are more communal, where spiritual practices and community support are not separate activities.

It feels like a new phase is coming in which engaged Buddhism will be more important than ever. As I like to say, time on the cushion is as necessary as time on the streets. Whether we ourselves suffer from intolerance, hate speech, violence, or discrimination, others surely do. Our practice is a support for all beings, human, insect, animal, and formless.

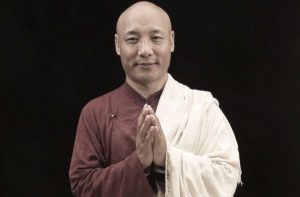

If meditation examines one’s mind, this must include our biases and assumptions not only about ourselves but about the world. All prayers we recite usually say “myself and all sentient beings.” So if we mean that, it includes others and the act of othering as well. Deconstructing our ego and our dualistic thinking means also addressing racism and all bigotry, including exclusion and dualism. These can be overcome together, not as two separate projects. Enlightenment is not supposed to be solely for oneself—bodhicitta cultivation is for the benefit of all. Therefore, engaged Buddhism is a natural outgrowth of prayer, meditation, and contemplation of the Buddha’s teachings and of his actual example during his lifetime. Teachers, from Lama Rod Owens to Thich Nhat Hanh to Joanna Macy, share perspectives related to engagement as a spiritual path. In one interview, the Korean Dharma master Ven. Pomnyun Sunim shares:

“We face many social issues today. The question is, from what perspective will we approach today’s reality? If the Buddha were to come to this world again, how would he approach environmental and peace issues? I believe that engaged Buddhism is not just a new form of Buddhism, or a part of Buddhism, but the very essence of Buddhism. In other words, instead of asking, ‘How should Buddhists participate in solving social problems?’ Buddhists should naturally participate in solving social problems.

“Some people ask me: ‘Why do you engage in environmental activism?’ To this, I respond: ‘I breathe, I drink water, and I eat food. How can I not engage in environmental activism when the things essential for my survival are being polluted and destroyed?’”*

These thoughts and statements make the very basis for engaged Buddhism clear, although many will contend that all they can do is work with their mind. Since the mind is the root of all experience, including suffering and misapprehension, this is more than enough. But for those of us capable of also acting in support of justice for beings and the planet, the path includes view, meditation, and skillful action. The view of cultivation is the basis for examining our own mind to ensure our actions will be for others, not merely for selfish gain.

* INEB Conference 2024: Tracing the Roots of Compassion and Equity Through Inclusive Social Engagement (BDG)

Related features from BDG

Reviving the Dhamma: Ambedkar’s Impact on Empowering the Marginalized through Buddhism

Dharma Drum Mountain and the Legacy of Chan Master Sheng Yen: A Conversation with Ven. Guo Huei

Practicing Equanimity in the Face of Injustice: Social Activism and the Middle Path

Is This Buddhism? The Oneness of Spiritual Liberation and Social Justice