I feel grateful beyond belief that I have been born in today’s times. This might seem like a strange thing to read, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic and the global climate crisis. But as a Buddhist woman, this is a good time to practice.

Women have studied and practiced Buddhism since the time of the Buddha. It is known that Siddhartha Gautama’s step-mother, half-sister, and wife were some of his earliest students. Siddhartha’s step-mother Mahaprajapati, who adopted him after his own mother died, later became the very first Buddhist nun. Sundari, his half-sister, became a nun and also attained awakening after struggling with her own attachment to beauty and the body, eventually transcending this clinging through practices on impermanence. Yashodhara, Siddhartha’s wife, became an ascetic and entered the order of monks and nuns, with time attaining the state of an arahat. It is clear that a female Buddhist sangha has been around for 2,500 years, from the very beginning of Buddhism.

In my own sangha, women outweigh men in terms of numbers by about two to one. The website Statistica reports that across the world in 2016, Buddhism was made up of 54 per cent women and 46 per cent men (no mention of non-binary data). Women are drawn to the study of Buddhism and apply themselves diligently to the various meditation practices.

The Buddhist teachings are also extremely inclusive in the sense of including equitably the value of the male and female principles. This shows up as the wisdom and means principles, or the sword and stream, or bell and dorje. There is such balance and appreciation for the female aspects, to be found in men and women alike.

However, women are still grossly underrepresented as Buddhist teachers. In this regard, many of us are “First Gen.” It is new that we have female teachers as role models for awakening. There are not many role models to take us all the way to awakening that look like us—women. There are even fewer female teachers who also represent BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), and truly gaining a balanced representation of BIPOC female teachers is of urgent importance for all Buddhists. Without mentorship, it’s hard to imagine what is possible.

Women seem to have to work harder than men in society to be noticed for what they do. Their style of leadership tends to be more understated compared to men. This might come down to biological and neurological differences between genders as well as societal training. It’s possible that people expressing gender fluidity or people with non-binary genders might help to clarify these influences more in coming years and we will listen to these experts about their experiences.

In the world of education, the “First Gen” movement in North America has been created to provide financial aid and psychological support to first-generation students whose parents did not attend college or university. In the education world, it is known that there is a psychological barrier to believing one is qualified or capable of handling the higher-education opportunities, and without support these students will not be successful and graduate. In essence, first-gen students have no role models within their families and lacking a role model holds them back. The movement recognizes that potential students need more than just financial aid. They need a system that tells them they deserve to want to be included and provides the emotional support to imagine such a future of belonging.

It seems that we generally have a similar issue with Buddhist women, who are also not quite sure that they deserve to strive for awakening. The Buddhist scriptures are becoming open to us. And as we slowly strip away the cultural barriers, more and more women, particularly North American women, see that spiritual awakening is available to all, male and female alike. This may be happening around the world, but it seems to be happening more quickly in North America, where societal values of equality between genders is a human rights intention, even if some might argue that it is not truly realized in all aspects of society.

But knowing that awakening is not limited by gender is not the same as believing it in our beings. We need role models around us. And here is where we are still sorely lacking. There are very few highly recognized female Buddhist teachers in North America. The few that are teaching, are mostly still teaching under male teachers, which leads us to view their awakening and realizations at a lower level.

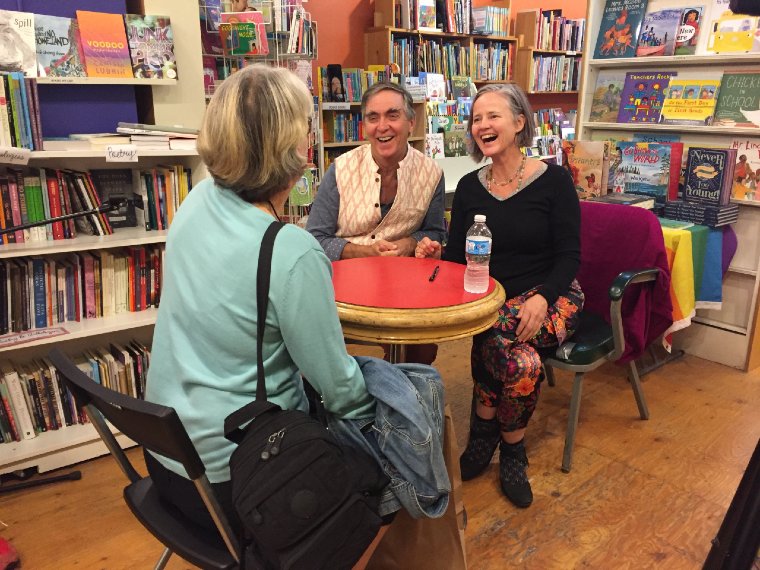

In this way, I feel fortunate that I have finally found a female teacher and an awakened being as a role model for myself and my own teaching. I have been studying with Catherine Pawasarat Sensei for the last 10 years. She is a lineage holder who studied with Namgyal Rinpoche, the first North American-born tulku (b. 1935). She later became an attendant and consort to Doug Duncan Sensei and continues to teach side by side with him. It feels significant that they sit and teach side by side and present a true blending of the male and female aspects. Together they have founded, developed, and are resident teachers at the Clear Sky Meditation and Study Centre in British Columbia, Canada.

While I feel blessed in many ways to have found a female teacher, the journey to accept her authority has not been easy. Her style is so different from many male Buddhist teachers. Her interests and talents lie in written and verbal communication, and she demonstrates a sharp articulation with words. She worked behind the scenes for many years supporting the teachings with her great organizational skills. She multitasks well and constantly has a vast number of projects going at the same time, and easily moves back and forth between the projects. As a woman, she is not as assuming and more modest with her achievements, despite her experience. I have struggled in the past to acknowledge her realizations, and only really noticed them when the male teacher honored them, something indicative of the gender bias not only of Catherine Sensei but also of myself.

The female awakened mind actually looks and feels different when viewed through the unawakened female mind. At the absolute level, the awakened mind is the same regardless of gender, but it comes through differently at the relative level. She has the total respect of her teacher, but not necessarily other male students, who see her more as a consort and partner than an equal in terms of teaching. It’s easy to see the role of consort—usually female—as less than the teacher—usually male—rather than simply a different but equal role, through the North American duality division of male-female. A consort traditionally has much to teach a practitioner, and this equality is often lost in the naming of the teacher as the awakened being and the consort as the support role. This actually reflects a Western division of labor that puts men higher than women, something that is not inherent in Buddhism. As a female myself, I seem to have an easier time recognizing the different skills and means that a female brings to the spiritual path, including the role of consort, which in Catherine’s case includes a deeper appreciation for community and the communication skills needed to interact with sangha members.

Some days, Catherine’s role as guru is even more elusive to me because she and Doug co-teach as equals on the meditation cushion. My mind literally splits when it tries to take this in as it struggles to push the awakened mind into the body of one male teacher. It does not naturally rest in the acceptance of Catherine as a teacher unto herself. It flits back and forth between the male and female energies manifesting in front of me, urging me to look deeper into the essence of guru, which knows no boundaries of gender or even one body.

When I first started studying with Catherine, she only in her 30s, five years younger than me, while I was already in my 40s and deep into my parenting years. She lived the life of a nomad, traveling and teaching around the world with no dependents. I often felt that she couldn’t possibly understand my life as a working mother with three kids and a full-time job. In some ways, I was jealous of her life choice and considered it a real option for myself, but a path deliberately not chosen. I worried that she didn’t understand how hard I juggled my parenting and work responsibilities with my spiritual aspirations. I found I understood and in some ways was jealous of her path, but I thought she couldn’t understand mine. Eventually, I learned to accept her encouragement of my path, even though she could only do so as an outsider. I accepted this and found I could share it with her after all. I learned to see that she had learned to transcend the gender divide and was able to connect with mothers and non-mothers—as well as males and females—and that my division of parents and non-parents was an arbitrary line in my own mind, not hers.

Interestingly, I admit that I longed to have my motherhood choice shared by Catherine Sensei, a female teacher, more than from Doug Sensei, a male teacher. I expected her to mirror “self” to me, as female like me, while I could accept Doug Sensei being different from me and choosing a different path as he was already “other” to me. These expectations are not conscious, but have become clear to me after consideration. I realize that this isn’t fair, but it is what comes up for me as a female. Perhaps it’s similar for my husband in what he expects from Doug Sensei and not what he expects from Catherine Sensei.

And then for me, accepting a female teacher as a role model became a stepping stone to accepting and understanding group guru—the manifestation of the deepest teachings in one’s community of practitioners. Having moved beyond thinking that only a male can manifest the awakened mind and learning to recognize the awakened mind in female form, it is easier to see when several sangha members working together are manifesting group guru mind. Such is the teaching of group guru and the possibility this opens up for multiple leaders in a more communal form. It is simply awesome to think that having greater diversity between genders and people who are parents, as well as those who are single, opens up possibilities that truly transcend ego and increase the opportunity for awakening.

Now that I have become a teacher myself, this interplay of self and other is all the more pronounced. In the multicultural and pansexual diversity of Toronto where I teach, I recognize how my unconscious biases show up with my students, despite my best efforts to be open-minded. I worry that I don’t really “see” everyone fairly as they want to be seen. I try to see the buddha-nature in each of my students and to help them see this too. I fall down sometimes by not understanding others’ life choices that are different from mine.

For example, I teach end-of-life support to Buddhists from other traditions and struggle to accept the reluctance to talk about impending death with the dying person. They might say prayers for the dying person in a different room, but never speak about the dying process together. I wonder how much of this is related to culture and find my mind jumping in to judge them, despite my intentions. I think my training as a female teacher helps me to be aware of this judgement, even if I can’t stop it completely.

Pushing myself to accept this loosening of boundaries of the awakened mind is what has helped to propel my own realizations. Buddhists talk about the first stage of awakening, srotapanna, as “realization by hearing,” and this reflects the importance of hearing and enlightenment. Hearing the actual voice of the teacher so frequently that the voice becomes a part of oneself is a practical and useful step leading to the srotapanna moment. I have heard Catherine’s voice speaking to me during meditation practices and have learned to recognize it as unique and personal. I know deeply that hearing the voice of this female teacher has been an important, if difficult aspect of these realizations.

Having a female teacher points the way to female possibilities for me in a way that no amount of study with a male teacher will ever do. I feel the possibilities for this female body in a way that no words of acceptance could ever bring. As I walk my own awakening path and develop my own Buddhist teaching style, I lean heavily on the example I see in front of me. I thank Catherine Sensei for showing me what is possible, and am grateful to her and to all the other unrecognized and forgotten female teachers before her.

May we bring the real possibility of awakening into all consciousnesses.

Linda Hochstetler, MSW RSW, is the author of 21 Days to Die: The Canadian Guide to End of Life (Sumeru Books 2021). As a well-known Canadian expert dealing with end-of-life issues, she has worked and taught at a variety of hospice palliative care programs, and runs a busy private practice specializing in illness, dying, and death. She has also offered grief counseling in the workplace and delivered Critical Incident Responses across Canada. She presents regularly at hospice palliative care conferences and symposiums throughout North America, hosts Death Cafés, and encourages everyone to talk more openly about their inevitable deaths. Hochstetler is both a registered social worker and Buddhist lay chaplain, and has been teaching mindfulness and Buddhist meditation for more than 20 years.

See more

Linda Hochstetler

Women and Buddhism (Planet Dharma)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Book Review: Tatiana Elle’s Yoga for Women: 45 Poses for Physical, Emotional & Spiritual Wellbeing

The Heritage of Buddhist Women in Mongolia: A Conversation with Kunze Chimed

Women in Buddhism: Breaking Gender Stereotypes

Women in Contemporary Buddhism: A Challenge for the 21st Century

Related news reports from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhist Actress Chantal Thuy Recognized among Extraordinary Asian and Pacific Island Heritage Women

Sakyadhita Spain to Host 2nd International Symposium of Spanish-Speaking Buddhist Women

1,600 Women Join 400-year-old Archery Tournament at Kyoto Buddhist Temple

BBC Names Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, Thailand’s First Female Monk, among 100 Influential Women of 2019