Saint Petersburg’s only Vajrayana temple stands proudly by the northern bank of the chilly Greater Nevka, at the corner of Primorsky Prospect-Maritime Avenue and Lipovaya Alley. Datsan Gunzechoinei is a magnificent hybrid of Tibetan, Mongolian, Buryat, and Russian architecture (where else do you see a Vajrayana temple with a granite facade and columns, exterior glazed tiles, and a modernist, stained-glass plafond?), surrounded by quiet woodland. This August marked its 100th anniversary, although dates are loose. Its first service was held on 21 February 1913, yet construction was not completed until 1915. The festivities saw a special appearance by lama Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche, who is famous in international communities and among European Russian Buddhists residing in Saint Petersburg.

“There’s actually much more activity outside this temple,” says Dr. Andrey Terentyev, editor of the Buddhism of Russia website (Russian only). “These days, Datsan Gunzechoinei is mainly a Buryat ethnic Buddhist center. There are several Buddhist groups in Saint Petersburg; some of them were active underground even in the 1970s. This year, Buddhists also celebrated the 250th anniversary of the title ‘Pandito Khambo Lama,’ which is bestowed on the head of the Buryat Buddhists,” he tells me. Whoever held—and holds—this title is a figure that exerts a decisive and prominent role in Buddhism’s relationship with Russia’s rulers.

Already a decade ago, Elena Ostrovskaya of Saint Petersburg State University lamented the lack of English-language material on Russian Buddhism (Ostrovskaya 2004). It remains the same today, though it is not exactly fair to speak of “Russian Buddhism.” It’s safer to speak of the four Vajrayana schools and the three ethno-religious traditions of the Buryats, Kalmyks, and Tuvans. “Buddhism is treated now in their republics as the symbol of national identity—it is important after the long years of Russification. The Kalmyks are more fortunate than the Tuvans or Buryats because they have Kalmyk-Philadelphian lama Telo Tulku Rinpoche, who is energetically ministering to the Buddhists in his republic,” says Dr. Terentyev.

For both Buddhists and the Romanov imperial dynasty, 1741 was a crucial year. Empress Elizabeth Petrovna (r. 1741–62) declared Vajrayana an accepted religious creed right in her first regnal year, marking the official recognition of Buddhism in Russia (Bernstein 2006, 27). The legitimation of rulers by Buddhists was no better exemplified than by the partnership between Catherine the Great (r. 1762–96) and a conclave of Buryat lamas, who apparently declared her an incarnation of White Tara in 1766 (Snellgrove 1987, 151). The title of Pandito Khambo Lama, the figure Dr. Terentyev mentioned to me, had been granted to the Buryats two years earlier.

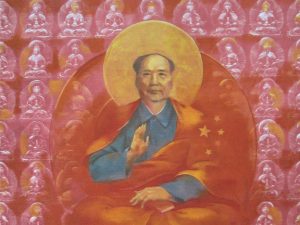

The Russian autocrat might have believed herself the benevolent assimilator of her empire’s Buddhists. But Buryat scholar Nikolai Tsyrempilov has a different perspective on the matter: Buddhism was not subsumed into pax rossiya, but rather pax buddhica, or the Buddha himself, claimed the empress’s body (Tsyrempilov 2009, 105–30). The Tsarist monk-diplomat Avgan Dorzhiev (1854–1938) was famous for his bond with Nicholas II, who supported the construction of Datsan Gunzechoinei despite a wave of anti-Buddhist protests against the temple. This tradition of “claiming” the Russian ruler’s body continues today, long after the tsars: Anya Bernstein of Michigan University reminds us that it was not so long ago, in August 2009, that the current Pandito Khambo Lama declared Dmitry Medvedev an embodiment of White Tara. This was done during the former president’s official visit to the Ivolginskii monastery in eastern Siberia, incorporating Mr. Medvedev into the world of Buryat symbolism (Bernstein 2012, 261).

British columnist Peter Hitchens was right to say that Russia is not the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union is an important part of Russian history but it is by no means the definitive expression of Russian identity. Those fixated on the USSR’s collapse underestimate the continuity of Russian identity. The political circumstances of the Tuvans, Kalmyks, and Buryats reflect a similar continuity: staking a claim on minority identities while tying that very identity to the ruling Russian polity. Their centuries-long efforts only really paid off in 1905, when Buddhism acquired legal status as the local religion of the ethnic minority groups (Ostrovskaya 2004). We come back full circle to Saint Petersburg in the late 1980s to 1990s, when the city became a hub for the revival of Buddhist practice. It was also when Russian Orientalism (or Russian Buddhology), once a methodology that could go toe-to-toe with the Franco-Belgian, Anglo-German, and Japanese schools of Buddhist Studies, rallied and reclaimed its reputation for anthropological expertise, particularly among the ethnic groups of Central Asia, Mongolia, and northern China.

“People are trying to revive the old traditions, old religious festivals, and other ‘ethnic’ features. On the other hand, a big part of the population lost touch with religion during the Soviet era and has no interest,” Dr. Terentyev tells me. “But dozens, if not hundreds, of Buddhist books are published every year in the Russian language. Though the general level of understanding Buddhism is rather primitive, it is growing little by little, and I think if we manage to organize a kind of Buddhist University in Moscow or Saint Petersburg, it will be a major step for our country. I see future Russian Buddhists as highly educated people: compassionate and searching for wisdom.”

If he is right, perhaps it has never been a better time to be a Buddhist in Russia.

References

Bernstein, Anya. 2012. “More Alive than All the Living: Sovereign Bodies and Cosmic Politics in Buddhist Siberia.” Cultural Anthropology 27:2, 261–85.

Bernstein, Anya. 2009. “Pilgrims, Fieldworkers, and Secret Agents: Buryat Buddhologists and the History of an Eurasian Imaginary.” Inner Asia 11: 23–45.

Ostrovskaya, Elena A. 2004. “Buddhism in Saint Petersburg.” Journal of Global Buddhism 5. http://www.globalbuddhism.org/toc.html (accessed 19 August 2014).

Snellgrove, David. 1987. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors I. Boston: Shambhala.

Tsyrempilov, N. V. 2009. “Za sviatuiu dkharmu i belogo tsaria.” Rossiiskaia imperiia glazami buriatskikh buddistov XVIII—nachala XX vekov. Ab Imperio 2: 105–30.