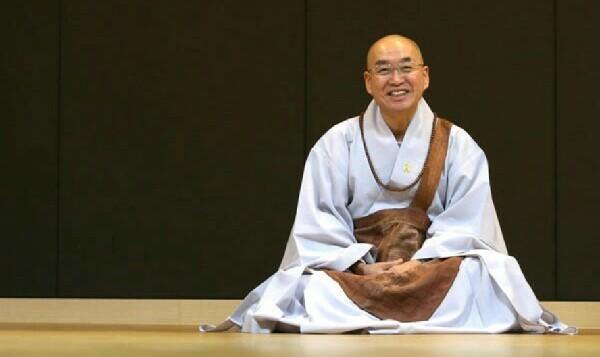

The Korean Seon (Zen) master Venerable Pomnyun Sunim (법륜스님) wears many hats: Buddhist monk, teacher, author, environmentalist, social activist, and podcaster, to name a few. As a widely respected Dharma teacher and a tireless socially engaged Buddhist in his native South Korea, Ven. Pomnyun Sunim has founded numerous Dharma-based organizations, initiatives, and projects that are active across the world. Among them, Jungto Society, a volunteer-based community founded on the Buddhist teachings and expressing equality, simple living, and sustainability, is dedicated to addressing modern social issues that lead to suffering, including environmental degradation, poverty, and conflict.

This year will mark the completion of Jungto Society’s first 10,000-Day Practice—a 30-year exercise that began in March 1993 with the aspiration to create “Jungto,” a society of peace, happiness, and sustainable existence living in harmony with nature. In conducting its 10,000-Day Practice, the members of Jungto Society have committed themselves to the practice of engaged Buddhism as well as their personal spiritual practice. This includes activities to promote environmental awareness, human rights, humanitarian assistance, and working toward peace and reunification on the Korean Peninsula.

Later in 2022, Jungto Society will host the 20th biennial conference of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), which will be held on the theme “Buddhism in a Divided World: Peace • Planet • Pandemic.” The conference will be a platform for socially engaged Buddhists to discuss and share strategies for expanding peace-building efforts, to collaborate on environmental concerns, to examine effective interventions for those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and to explore a wide range of issues of global concern.

BDG sat down with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim to hear his views on Buddhism in contemporary society. He shared his thoughts on the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of engaged Buddhism in the face of the human-made global crises that are challenging the world we share, taking on topics from environmental collapse, societal and economic inequality, and the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism, to the need for a profound transformation of our temporal and spiritual lives to create a sustainable global civilization that recognizes and respects the fundamental interconnectedness of all life.

BDG: 2022 is a landmark year for Jungto Society. The first 10,000-Day Practice began in March 1993 with the aspiration to create a society of peace, happiness, and sustainability founded on the Buddhadharma. Congratulations on reaching this remarkable milestone!

What was the original inspiration for this ambitious undertaking? Some people might even say it sounds too idealistic!

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Back in those days, Korean Buddhism was experiencing many difficulties. Sectarians within Buddhist society at the time were very divided. Their disagreements led to much disharmony and even physical conflict. The situation was such that it was not only covered by domestic media channels, but also by international media such as CNN.

In Korean society at large, which had suffered under a long dictatorship, we were starting to see the early successes of the pro-democracy movement. After the military dictatorship was finally removed from power, Korea started to see elected leaders placed in office by direct elections. Many young Koreans were directly involved in the pro-democracy movement.

After the first democratically elected government took office, and after Korea hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics, I think people started to recognize that they were finally living in a democratic society. And so the conditions were created that enabled people to engage in activism within their own communities—for example, workers could engage in the labor movement; farmers could engage in the agricultural movement; and women could engage in the campaign for women’s rights. Prior to this, only intellectuals led the movements in each sector of society.

The big question then became: if workers are engaged in the labor movement and farmers are engaged in the farmer’s movement, what would be the role of intellectuals? The public consensus at the time was that we should adopt a forward-looking attitude to shape the future direction of society and to expand Korea’s influence—not only domestically, but also in the international context.

During the time of the pro-democracy movement, the Buddhist community was preoccupied with internal strife. As a result they didn’t play a prominent role in the movement’s leadership. The Buddhist community came under significant criticism for this. Conversely, Christians were very active as leaders within the movement. Because of the Buddhist community’s indifference toward the social movement, I participated in the Christian-led campaigns.

At the time, I also held a firm commitment that over the course of the next 30 years, the Buddhist community should work to restore their leadership role in shaping the future of Korean society. I believed that it was important to recognize what we would need to do in order to build our future and also that we should act and respond preemptively to this obligation.

I knew that there were some people in the Buddhist community with wisdom, so I went to see them to hear their views on what we would need to do to build a better future. After three years of intensive discussions, we came to the conclusion that the environment was sure to be a critical issue in the years ahead. This was despite the fact that, at the time, environmental issues were not very high on the social agenda.

While I was incarcerated [during the brutal dictatorship of Gen. Chun Doo-hwan from 1979–88], I read a book titled Entropy* and I intuitively realized from reading this book that the environmental issue would be one of major significance. This is because economic development and growth inevitably brings about environmental damage. We therefore came to the conclusion that environmental sustainability is a fundamental global issue.

We Buddhists practice every day to reduce our desire, which is also related to overcoming consumerism. I quickly realized that Buddhism is intimately related to the environmental issue. I knew that we humans cannot fundamentally resolve our environmental problems when we look upon nature as something to be conquered or subjugated. This is a common view of modern civilization. Because the Buddhist teaching is based on the understanding of dependent origination, I believe that environmental crises can only be addressed through understanding the principle of the interconnectedness of humans and nature, of all things.

From the Japanese colonial era to the division of the Korean Peninsula, and then to military dictatorship, South Korea’s domestic issues have long been the most difficult and pressing issues for our society. During the colonial era, the revolutionary movement was the most important, overarching issue. With the Korean War, peace and reunification became the most crucial problems to address. Under military dictatorship, the pro-democracy movement was at the forefront.

Because we were so focused on resolving our domestic issues, we didn’t have the ability to look outward to the rest of the world. But after the 1988 Summer Olympics, we realized that our economic growth had already reached the ranks of the advanced economies. So we came to the conclusion that the poverty issue was not only an issue for other advanced economies to address, but that we were also responsible—up until that point, we had always been on the receiving end of aid and assistance from the West. During the pro-democracy movement, assistance from Germany and the US came to us through Christian organizations, which also founded the labor and pro-democracy movements. We also adopted methods for education and advocacy activities learned from the West. So I think it’s fair to say that we were accustomed to being on the receiving end of assistance.

It was then that we understood that we, too, bore a responsibility to help lift the poorest countries out of absolute poverty. We realized that relieving and eliminating absolute poverty was the most globally pressing issue at that time. And we recognized that the issues of hunger and disease and illiteracy are not just problems of a certain segment of society, but that humanity as a whole has a responsibility to address those three issues. The standard at that time for absolute poverty was an income below US$1 per person per day. So we set a goal of donating at least US$1 per day each to alleviate poverty, and then after that we could use our remaining money to build our own lives.

On the Korean Peninsula, not repeating the war was at the forefront of most people’s minds. During the 1950–53 Korean War, 2.8 million people died, and 10 million people were separated from their families by the division of the North and the South. This issue remains unresolved to this day. If war were to break out again, then the damage would be enormous. That’s why we believe that building peace is the overarching focus for the Korean Peninsula.

Observing globally, there is one region in particular in which the three issues of hunger, disease, and illiteracy have been largely resolved. That region is Northern Europe: Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden all share the commonality of natural beauty, low absolute poverty, prosperity, and peace. Yet that region also had one of the world’s highest suicide rates at that time. Why did the people living there want to commit suicide? Because simply resolving social issues doesn’t mean that people are freed from their own suffering. The Buddha’s own suffering wasn’t resolved just because he was born as a prince.

That’s why in order to be happier and to be free, we need a practice to help us train our minds. Buddhism offers the best means to practice in this way—by which I mean Buddhism as a spiritual practice rather than Buddhism as a religion. I believe that Buddhist practice should be embraced by all people as a path to personal happiness, without being bound by the restrictions of religion or the conventions of society. And the practice of Buddhism should be undertaken with a view to social engagement rather than as a purely personal issue.

As such, we laid out four goals: people should find happiness through their personal practice; we should bring about peace on the Korean Peninsula; humanity should become free from absolute poverty; and we should find a way to address environmental issues such as climate change. We set out these four goals as the main objectives of our practice and we named this community “Jungto,” which means an ideal society founded on the Buddhadharma.

But what is “Jungto”? What is an ideal society?

The natural environment should be beautiful and protected. Human society should be peaceful. Individuals should be happy. These are the three basic elements needed for a Jungto Society; living with the Buddha’s teachings based on truth, not simply wishing for blessings and not discriminating against people based on status, or other perceived differences.

The second point is that the Buddhist teachings should be easily accessible and easily received by the public. The teachings should be something that we can easily practice in our daily lives. Therefore, the well-being of our families and the resolution of social issues should all come together and not be viewed as separate. It’s not as if society and individuals exist separately; they exist together. This is what we call simple Buddhism and practical Buddhism.

The Buddha began sharing the Dharma on his own. He didn’t have his own temple, he didn’t have any tradition to follow. In fact, he broke with tradition and as a result was met with resistance from established traditions. Instead, he started out by receiving alms for food, sleeping beneath a tree, and clothing himself in discarded rags.

What is it that we cannot do? Nothing can be solved by criticizing what is wrong in existing Buddhist traditions. Rather, perhaps we can see the beginnings of change if we look forward into the next 30 years. There’s an old teaching that has been passed down through the generations within the Buddha’s sangha: it takes 100 days of practice to reveal who we have become as individuals. It takes 1,000 days of practice to bring about actual change within ourselves, such as becoming less greedy or less angry. And it takes 10,000 days of practice to bring about change in the world.

This is why we started the first 10,000-Day Practice.

BDG: Did your vision of a community founded on the Buddha’s teaching changed during that time?

VPS: I wouldn’t say “vision,” but at the very least, existing Buddhism should not inflict any harm upon society. Many people were opposed to Junto Society in the beginning. But now, more and more people realize that perhaps Jungto Society represents hope for the future of Buddhism. In fact, in many respects, Jungto Society has received much more recognition from lay society than from the Buddhist community.

People have gained a good impression from our engagement in environmental campaigns, humanitarian assistance programs in North Korea, and our relief work around the world. Indeed, many other Buddhist organizations have been inspired by our work to engage in their own humanitarian relief activities, leading to the emergence of new social engagement movements.

On reflection, I think it’s fair to say that the direction of Jungto Society was right, but our influence has not been sufficient. Over the last three decades, we have attained our outreach aspirations in a qualitative sense, but not in a quantitative sense. Jungto Society has had a positive effect on the world, but not yet as much as we’d hoped to see.

BDG: A key feature of the Buddhist tradition has been the personal relationships between teachers and practitioners. The global shift toward online contact as a result of the pandemic has expanded the reach of Dharma teachers, yet depersonalized their interactions. How might such drawbacks be addressed?

VPS: The biggest advantage of this new paradigm from Jungto Society’s perspective is that our reach has grown, even to remote areas, no matter how far away people might live. Another advantage is that we’re no longer shackled by the limitations of physical space in bringing people together. A further advantage we’ve found is that it’s now easier to reach people who might otherwise not have been motivated to learn about Buddhism by attending a physical setting.

Now that it’s easier to have a direct relationship with so many people, it’s important to preserve that advantage; for example, it has meant that about 8,000 people participated in the recent semester of our online Jungto Dharma School.

But practice is defined by the characteristics of humanity. This means that human contact is needed in order that we can feel moved. So the benefits of our online outreach are also limited in terms of the emotional connection of direct human contact. As such, our online community carries the risk of being perceived as limited to simply disseminating the Buddhist teaching, instead of being truly awakened to the truth of the Buddhadharma through that vital human connection. In this respect, our remaining goal in adapting to this new medium is overcoming this limitation.

Also, only listening to online Dharma talks is often limited by being unable to participate in terms of service or engagement or personal practice. So we also need to focus on supplementing this shortcoming.

Before the pandemic, Jungto Society had more than 200 physical branches in Korea alone, but we decided to close them all because people could even hold Dharma meetings in their own homes. Instead, we established a few regional practice centers where people can come to do volunteer work (such as farming), meditate, or conduct prayer ceremonies in their free time or at the weekend.

Now we educate people online, so people can even join meditation sessions online from their homes, and can also participate in practice online. Offline, people can engage in environmental or aid activities. They can also do volunteer work such as farming and gardening. This is one way of supplementing the limitations of online Dharma communities, which is the lack of human contact and the lack of in-person practice opportunities.

But we should also remember that Buddhism has already evolved in the face of such changes throughout history. This can be seen in the communication of the Buddhist teachings; the way the Buddha shared his teaching with the world. Originally, it was an oral tradition. The Buddha gave his teachings orally and they were only shared through direct human contact. Later on, the Buddhadharma was recorded in written texts, in the form of sutras. This meant that the teaching could spread—from India to China and Korea, and so on, and that people could learn by reading these texts. This had an enormous impact on the global reach of Buddhism.

However, there was also a downside to this. As Buddhist books and texts became more widespread, the human and experiential aspects were omitted as books can only transmit Buddhism in the form of intellectual knowledge. So throughout history, we’ve witnessed the downside of the Buddhist teaching being transmitted as a form of knowledge and also the authentic spread of the global outreach of Buddhism as a spiritual practice.

This is why Buddhist developed as a form of knowledge in China. And that’s how Buddhist schools emerged to make up for the lack of human context in the books that contained the Buddhist teachings. It’s for this reason that Seon [Zen] Buddhism teaches that ultimate truth cannot be expressed in words. This is the essence of Seon Buddhism.

Therefore, I think that online Dharma today has an advantage compared with the past, when Buddhism was limited by being perceived as textual knowledge. Today the spread of the Dharma is much faster, and a side effect is a lower incidence of Buddhism being perceived as mere knowledge, because we can at least have the benefit of face-to-face contact online.

Another issue we’re facing is that Buddhist ideology has taken on a “digested” form—a shallower, more simplified version, rather than people contemplating or undertaking deep introspection of the teaching. Modern people have become accustomed to “fast knowledge,” so nowadays, the content needs to be short and interesting and to speak to the heart of the person, otherwise people might not see it.

So it might be an advantage, but it can also represent a disadvantage. Our task now is how to lessen that disadvantage over time—to focus on amplifying our advantages and reducing our disadvantages. We cannot prepare for every eventuality in advance, but we should work to tackle each task as our time allows, and see how things unfold.

BDG: The COVID-19 pandemic has also been a major disruptor for humanitarian work. What is the status of your efforts to help children and vulnerable people in North Korea?

VPS: Our humanitarian work in North Korea has been completely halted for two-and-a-half years. We have no way of doing anything in North Korea as the border is completely closed.

Instead, we have focused our attention elsewhere for the time being. For example, we have supplied 100,000 gas burners to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.** Our humanitarian work in India and the Philippines was temporarily suspended, but has since reopened. And we have been able to provide humanitarian aid to Myanmar, in cooperation with the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB).*** We’ve also been engaged in other projects in South and Southeast Asia with the help of INEB as we were unable to directly dispatch personnel to those areas.***

BDG: The theme of INEB’s 20th biennial conference this year, to be hosted by Jungto Society, is Buddhism in a Divided World. In a world that seems to be increasingly polarized, politically and socially, what in your view are the greatest challenges facing society today?

VPS: Fundamentally, I think the biggest challenge is consumerism. People mistakenly believe that excessive production and excessive consumption equate to more wealth. This has led to climate change and environmental issues. It has widened the wealth gap and caused economic disparities. And it has caused incessant suffering, even though in many cases we already have enough to make ends meet. What is realistically important is to address polarization.

First of all, economic polarization; the gap between wealthy and poor nations. And then within each country, there’s a gulf between wealthy and the poor citizens. And that gap is widening. It used to be that this wealth separation was about 80:20, which then shrunk to 90:10, and now further to 99:1. With this widening gulf, it’s inevitable that some societies are going to spiral into chaos and confusion.

The second issue is ideological conflicts. People tend to lack a complete understanding of others because they are exposed to one-sided information from social media and other online content. Yet even within a single social group, we can see conflicts caused by a widening generation gap. And within the borders of a single country, we see friction and conflict between conservatives and progressives. It’s not merely a competitive relationship, I think it’s fair to say it has become a hostile, confrontational relationship.

These intensifying conflicts are a global problem that is leading to situations of extremist and exclusionist elements. This is also resulting in intense jingoism and in some cases risks leading to all-out war. The ongoing Ukraine crisis, for example, is just the beginning; I anticipate more such conflicts emerging. In that sense, the risk of war on the Korean Peninsula has also increased.

BDG: Given the scale of these global crises and the deep systemic changes that are needed to respond effectively, how optimistic are you for the future?

VPS: Taking a long-term view, I’m optimistic, because people and societies will of course evolve through trial and error. Peace eventually came to us after the first and second world wars, but too many lives were lost in the process. But taking a short-term view, I can say I’m pessimistic.

I think it’s much more likely that people will continue to act out of ignorance and behave foolishly. Only afterwards will people and societies realize their mistakes and begin to undertake the real work that’s needed. Now, we can only do our best to prevent such conflicts, crises, and wars from arising. Only then, after we’re able to do so successfully, can we begin to lay out our direction for the future. This is the way that the human mechanism, human society works.

BDG: In that case, do you have any advice for our readers? How might ordinary people and lay practitioners play their part in helping to make the world a more peaceful place?

VPS: If we’re already on the right path, then the only thing we can do is simply to do our best, without being overly concerned about whether or not our efforts are actually successful. It’s not that our happiness is dependent only on our success or failure; happiness can be obtained through the process of striving toward our goals.

BDG: Ven. Pomnyun Sunim, our sincere thanks for sharing your time and wisdom with us today.

VPS: There’s an old saying that goes: “구슬이 서말이라도 꿰어야 보배다.” No matter how many beads you have, they only become valuable when threaded together—nothing is complete until it has attained its final form!

Similarly, no matter how beautiful the Buddha’s teachings are, they are effectively useless unless they can lead people to lift themselves out of their suffering!

With special thanks to the members of Jungto Society for making this interview possible.

* Rifkin, Jeremy. 1981. Entropy: A New World View. New York: Bantam Books.

** Korean Buddhist Humanitarian Organization JTS Brings 100,000 Gas Stoves to Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh (BDG), Buddhist Relief Organization JTS Korea Sends PPE to Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh amid COVID Fears (BDG), and UPDATE: Buddhist Relief from JTS Korea Transforming the Lives of Rohingya Refugees (BDG)

*** Engaged Buddhism: JTS Korea, INEB Distribute US$50,000 in COVID-19 Crisis Relief (BDG), Engaged Buddhism: JTS Korea Donates COVID-19 Relief Supplies to Myanmar in Cooperation with INEB and KMF (BDG), and Engaged Buddhism: JTS Korea Distributes Emergency Flood Relief in Cambodia (BDG)

See more

Pomnyun

Jungto Society

JTS Korea

JTS America

International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

Related features from BDG

Why Enlightenment?

The Hungry Should Eat: JTS Brings Buddhist Compassion and Relief to India

Engaged Buddhism: Seon Master Pomnyun Sunim Pledges 10,000 Tons of Food Aid for Children in North Korea

Engaging with Suffering, Realizing Freedom: An Interview with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim

Related columns from BDG

Dharma Q+A With Ven. Pomnyun Sunim

Related news reports from BDG

Engaged Buddhism: Ven. Pomnyun Sunim Shares the Fruits of Compassion to Mark the Birth of the Buddha

Jungto Society Launches Online Dharma School

Engaged Buddhism: Ven. Pomnyun Sunim Delivers Compassion to the Vulnerable in Korea

Engaged Buddhism: Jungto Society Delivers Compassion for the Vulnerable in Korea

Engaged Buddhism: Jungto Society Sharing the Gift of Compassion this Winter

Engaged Buddhism: JTS Korea Brings Warmth to Vulnerable Communities amid Winter Freeze

Related videos from BDG

Dharma Q+A with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim

Wisdom Notes from Ven. Pomnyun Sunim