Pure Land Buddhism has flourished in China for centuries. When we talk about Pure Land thought, we almost automatically equate it with that of one specific Buddha, commonly known as Amituofo (阿彌陀佛) in Chinese and Amitabha in Sanskrit. Followers of the Pure Land school often speak of Amitabha’s Land of Bliss as a realm to which they wish to ascend upon death. In this land devoid of suffering, pious devotees will be reborn on lotus flowers and listen to Amitabha’s preaching of the Dharma in divine joy. In this wonderful sphere of transcendence, as demonstrated by the sutra tableau (經變畫) in Cave 25 of the Yulin Grottos, even a little mouse has no worry over food, running around happily.

While Amitabha’s Pure Land has exerted a profound influence upon Chinese culture, there is more than one type of Pure Land documented and preserved in Buddhist texts and art. As author Tang Yongtong (湯用彤) remarked in The Historical Manuscripts of Buddhism in Sui and Tang (隋唐佛教史稿), faith in Maitreya’s Pure Land was once just as popular as that of Amitabha’s. Masters of the Faxiang school or the Dharma-image school (法相宗), including the widely known Xuanzang (玄奘, 602–64), expressed their fidelity in Maitreya. The first female emperor Wu Zetian (武則天, 624–705) was proclaimed to be an incarnation of Maitreya Buddha. In a time when faith in Maitreya prevailed through the joint effort of monastics and politics, how might common people have envisaged this Buddha’s Pure Land?

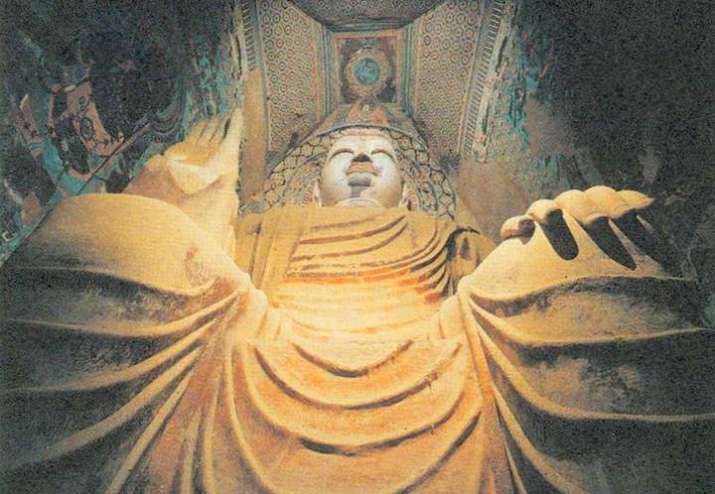

In the same temple cave of the Yulin grottos, opposite the sutra tableau of Amitabha’s Land of Bliss, is a representation of Maitreya’s Pure Land. Yulin is located in a valley not far from the Mogao grottos of Dunhuang. For a long time, Yulin was also referred to as Ten Thousand Buddha Gorge (萬佛峽), a name used, for instance, by Matsumoto Eiichi (松本荣一) in his studies of Dunhuang iconography. Mural paintings in Yulin have been better preserved because they are not as well known as those of Mogao. Up until now, many details remain visible.

Most pure land tableaux have a similar layout: usually the Buddha in charge of this realm will sit in the center accompanied by two bodhisattvas, and on the peripheries, stories from sutras are depicted in a wide variety of styles. When we enter the main chamber of Cave 25, on our right, there is Amitabha’s western paradise. Devotees are being reborn on lotus flowers. Bodhisattvas listen to Amitabha’s preaching. A plump deva expresses her joy in a euphoric dance.

To our left stands a similarly structured tableau of the Pure Land of Maitreya. However, Maitreya Buddha does not preside in a heavenly realm. Rather, as expressed by the mural, this Buddha descends to the human realm to preach wisdom and compassion. Therefore, on the peripheries of the tableau, we found stories documented by Kumarajiva (鳩摩羅什, 344–413) in his translation of the Sutra of the Descending of Maitreya (彌勒下生經). As such, we are presented with the following episodes: once upon a time, there was a kingdom ruled by a benevolent king. People enjoyed long and flourishing lives. Women would not get married until they were 500 years old. Nonetheless, even in this prosperous kingdom, suffering, craving, and attachments remained. To help sentient beings in this kingdom, Maitreya Bodhisattva, who was residing in his Tushita Heaven, descended to the human realm and was born as a human in an average family.

Young Maitreya came to realize the egoism of his fellow citizens when they stole the jewellery on the pagoda awarded to him by the king. Deeply disappointed, Maitreya converted to Buddhism, attaining awakening under a dragon flower tree. Maitreya then preached the Dharma three times to awake others. All the citizens, following the lead of the king and the nobles, became Maitreya’s disciples. Eventually, Maitreya visited Mahakashyapa to retrieve Shakyamuni’s robe, indicating that Maitreya is the legitimate successor of Shakyamuni and the Buddha of the future.

The motif of the Maitreya tableau is sharply different from that of Amitabha, insofar as the Pure Land is no longer portrayed as a heavenly realm, but as a place where we reside right here right now. Contrary to the idea of the Pure Land as a place of the life to come, in Maitreya’s Pure Land devotees conduct moral actions to construct a prosperous society, in deep faith that one day in the future, the Buddha will come to their realm to guide them in realizing the Land of Bliss. No wonder even Wu Zetian would proclaim to be the reincarnation of Maitreya: a clever way of legitimizing her rule and her authority with the blessing of Buddhism.

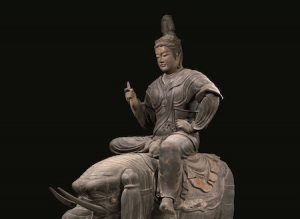

The image of Maitreya Buddha in the tableau might strike readers as quite unfamiliar. Indeed, the image of Maitreya Buddha, which is ubiquitous in everyday life, presents this Buddha as big bellied and laughing. This icon of a laughing Buddha, in fact, did not appear until the Song dynasty. Prior, Maitreya was envisaged in two ways: either as a bodhisattva taking residence in the Tushita Heaven, crossing his legs in meditation, or as a Buddha descending to the human realm and preaching the Dharma. When preaching, Maitreya Buddha would put his legs down naturally rather than crossing his legs. This is how the image of Maitreya Buddha can be demarcated from that of others.

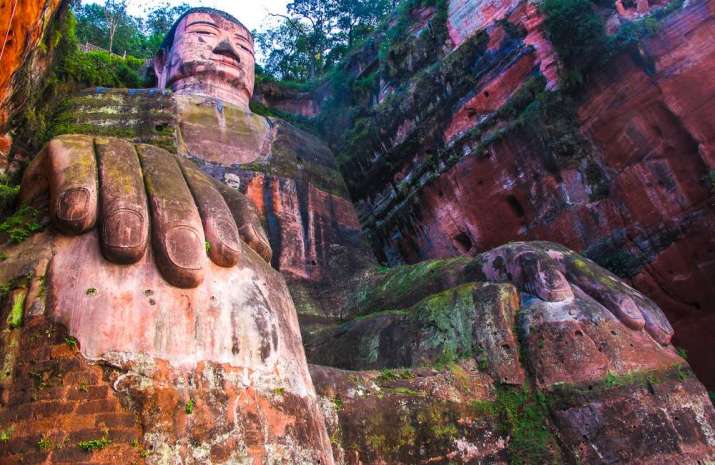

Today, when we travel around China, we see a lot of Maitreya statues. The tallest stone Buddha statue, namely, the Giant Buddha of Leshan (樂山大佛) in Sichuan Province, depicts Maitreya. Wei Gui (韦皋, 745–805), a respected official from the gentry family of Wei at that time, supervised the construction of the statue and wrote the inscription for the stone tablet in memory of this event. The inscription mentions the same idea of awaiting the future Buddha to guide us in constituting a Pure Land on Earth: “Due to the faith in the cause of the future, we erect the statue of Maitreya; we, the humble ones, will go through all the kalpas and engage in the training infinitely (由是崇未來因,作彌勒像,俾前劫後劫,修之無窮).” Likewise, two giant stone Buddha statues in the Mogao Grottos, namely the South Giant Statue (南大像) and the North Statue (北大像), both represent Maitreya Buddha, the salient feature of which is, undoubtedly, the naturally lowered legs.

Belief in Maitreya Buddha finds its doctrinal roots more clearly in the writings composed by clerics of the Faxiang or Dharma-image school. Historically, Maitreya is said to be the founder of the Yogacara school of consciousness-only (瑜伽行唯識學) in India. Yogacara Buddhism was promoted particularly by the Faxiang school in the Tang dynasty. Kuiji (窺基, 632–82), the disciple of Xuanzang, wrote in the Treaty of the Mahāyāna Dharma Garden and Forest of Meanings (大乘法苑義林章) that the heavenly realms created by various Buddhas manifest the compassion for other sentient beings.

As such, these realms are not ultimately real but serve as expedient, provisional means. What is real is our own realm, the place in which we live, right here right now. The story of Maitreya descending to the human realm embodies the same leitmotif: Maitreya was a bodhisattva who resided in the heavenly realm of Tushita and welcomed sentient beings to ascend to his Tushita Heaven. Yet he did not realize his Buddhahood or become a Buddha until he left Tushita and came down to our realm. Maitreya Buddha, the literal meaning of whose name is the compassionate one (慈氏), would guide regular beings like us and collaborate with us to constitute the Pure Land of awakening.

Articulated as such, the Pure Land is no longer the transcendent Tushita heaven but the ideal society to appear through our collaborative effort on Earth.

Even in the modern era, many eminent Buddhist masters, such as Xuyun (虛雲, 1840–1959), Taixu (太虛, 1890–1949) and Yinshun (印順, 1906–2005), continued to express faith in Maitreya Buddha. Undoubtedly, it is not the big-bellied laughing Buddha but the compassionate one that they were revering. For them, the real Pure Land would be the one we constitute together under the guidance of Maitreya Buddha. Therefore, they conceive of the ultimate Land of Bliss as the one to appear upon Maitreya’s descent. It is thus very different from the conception articulated by Matsumoto Bunzaburō (松本文三郎), for whom the establishment of faith in Maitreya’s Pure Land was marked by the idea of ascending to the Tushita Heaven.

Today, we still do not know how much this idea of Maitreya’s descending to the human realm has influenced the notion of humanistic Buddhism articulated by Taixu and Yinshun. Nor are we positive about whether the Yogacara revival in early modern China stimulated the idea of the rediscovering the conception of Maitreya’s Pure Land on earth. These would be fascinating questions for scholars to explore in the future.

This article is part of “Buddhism in the People’s Republic,” a special project focusing on the schools of Mahayana Buddhism in contemporary China. Through this project, Buddhistdoor Global’s editorial team and expert contributors aim to provide a concise, insightful, and informative overview of the history of contemporary Chinese Buddhism, and the modern practices and influences that are shaping the changing face of modern China. Return to Buddhism in the People’s Republic