Tibetan yoga is the hidden treasure at the heart of the Tibetan Tantric Buddhist tradition: a spiritual and physical practice that seeks an expanded experience of the human body and its energetic and cognitive potential. This is the subject of a fascinating new book by Ian A. Baker, Tibetan Yoga: Principles and Practices (Inner Traditions 2019).

Baker studied literature and comparative religion at Oxford University and Columbia University, then lived for more than 25 years in India and Nepal, where he studied with some of the greatest teachers of the Tibetan tradition, including His Holiness the Dalai Lama. In his remarkable book, Baker introduces the core principles and practices of Tibetan yoga, alongside historical illustrations of the movements and beautiful, full-color works of Himalayan art, never before published.

Buddhistdoor Global: What is the place of yoga practice in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition?

Ian A. Baker: Tibet’s Vajrayana or Tantric form of Buddhism is based on Indian Sanskrit texts known as yoga tantras, in which the word yoga refers to expedient methods for realizing one’s innate buddha-nature or enlightened awareness, and tantra to methods that expand on pre-existing Buddhist sutras. In this sense, all Tibetan Tantric Buddhist practice is yoga, ranging from deity yoga, in which practitioners imaginatively identify with divine archetypal beings, to dynamic exercises through which practitioners embody those deities’ enlightened qualities, to the “supreme” (ati) form of form of yoga, in which practitioners directly align with their indwelling buddha-nature. This triune process represents three successive phases of Tantric Buddhist practice: the Creation Stage (Kyerim), the Completion Stage (Dzogrim), and the Great Perfection Stage, known in Tibetan as Dzogchen.

In the earliest transmission of Buddhism to Tibet these three successive phases are referred to as Maha Yoga, Anu Yoga, and Ati Yoga. Breath-based bodily movements—analogous to modern “flow” yoga—are traditionally undertaken during the Completion, or Anu Yoga, Stage of Tibetan Buddhist practice to optimize the body’s internal energy system and enhance meditative clarity and non-discursive awareness.

BDG: When and how did you begin exploring the hidden treasure of Tibetan yoga?

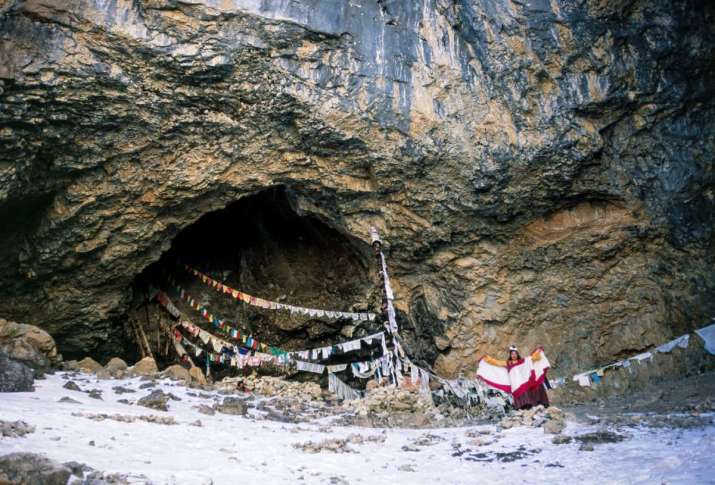

IAB: In 1977, I traveled to Kathmandu on a college semester abroad program and met my first Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Dudjom Jigdral Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche. I began living in Nepal from 1984 and studied with other great Tibetan Buddhist masters, such as Dhungtse Thinley Norbu, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche. None of my teachers were monastics, and they all encouraged me to practice in remote mountain settings in accordance with early Tibetan traditions. This very much appealed to my own nature, and oriented me toward the more embodied Buddhist practices espoused in the original Indian Buddhist Tantras.

BDG: The book is illustrated with your exceptional photographs and impressive full-color works of Himalayan art. What is the source of these priceless images and materials?

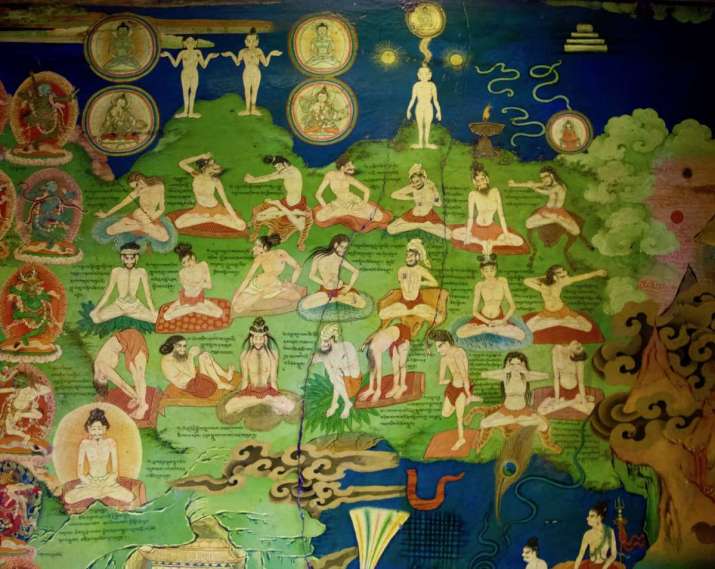

IAB: The illustrations in Tibetan Yoga reflect the more than four decades that I have been immersed in these practices. I had the great fortune to be able to travel widely throughout the Himalayan world and to meet many great female and male practitioners. Many of the photographs in the book result from such meetings. Other images are from remote monasteries and rarely visited temples where some of these yogic practices are illustrated in mural paintings or in manuscripts. Some of the great artwork that features in the book is courtesy of private collectors, museums, and contemporary artists.

(beb) from the Rigdzin Trulkhor cycle of the Longchen Nyingthik.

Gaden Lhakhang, Ura, Bhutan. Photo by Ian Baker

BDG: Yoga practices have traditionally been kept secret in Tibet because they can easily be misunderstood. How can revealing such secret practices benefit Buddhist practitioners without breaking tradition?

IAB: It is because of extensive misconceptions regarding Tibet’s inner tantric tradition—in particular the Completion Stage—that I felt compelled to share what I have learned through firsthand study and experience. We live in an era in which all aspects of tantric practice can be learned about online, but confusion among practitioners continues to exist as a result of partial or incomplete understanding. My book is thus an attempt to clarify misconceptions by contextualizing so-called “secret” Tantric Buddhist practices historically and anthropologically.

When we look historically, for example, we see that Tantric Buddhist practices based on one’s inner yogic anatomy (Tsalung Trulkhor) were originally taught openly and without restrictions. Some attitudes of secrecy within Tibetan Buddhism can be directly traced to the incompatibility of certain yogic practices with Buddhist monasticism. As the vast majority of contemporary Tibetan Buddhist practitioners in the West are not inclined to monasticism, it seemed important to clarify the non-monastic yogic practices that Tibetan tradition itself upholds as being the swiftest path to enlightenment. Even though potential dangers of misapplication remain, the book is by no means an instruction manual and points continuously to the importance of learning firsthand from qualified mentors. The book also emphasizes the importance of foundational Buddhist principles such as equanimity, compassion, and interconnectivity (Skt: shunyata).

BDG: How does Tibetan yoga facilitate the Buddhist aim of transcendence of the self and the attainment of enlightenment?

IAB: Tibetan yoga, in the context of my book, refers specifically to the deeply embodied Completion Stage practices that traditionally follow foundational Creation Stage practices based upon focused attention and creative visualization. In Creation Stage Deity Yoga, practitioners transcend habitual self-conceptions by imaginatively transforming themselves into a tantric deity. In one sense, we can understand this process as a form of “method acting” that reveals the fluid nature of self-identity.

Completion Stage practices traditionally involve a sequence of six yogas. These begin with reflections on the insubstantiality of human embodiment (Illusory Body Yoga) and proceed with dynamic breathing and yogic exercises (Tsalung Trulkhor) that support the yogic cultivation of Fierce Heat (tummo). The exalted consciousness that arises from activating the body’s inner energy system leads to the subsequent yogas of Clear Light, Dream, Transference of Consciousness, and navigation of a visionary postmortem dimension known as the Bardo. These Six Yogas of the Completion Stage also encompass consort practice, or Karmamudra, so as to transform objectifying desire into non-dual, ego-transcendent bliss and luminosity.

The Six Yogas of the Completion Stage actively cultivate wisdom, compassion, and altruistic action and can be integrated into all phases of existence. They were originally taught outside of monastic environments by female and male mahasiddhas of eighth–11th century India. They were later adapted into Tibetan monastic culture where they were often obscured by conventions of secrecy. Despite their applicability to everyday life, the six yogas are now mostly transmitted in the context of three-year meditation retreats. It’s my hope that these deeply embodied and accessible practices that represent the core essence of the Tantric Buddhist Completion Stage will become central to transnational Vajrayana Buddhism in the 21st century. In my own experience, this inner methodology of the Buddhist yoga tantras offers the most viable approach to realizing Buddhism’s perennial goal of universal enlightenment.

BDG: Ian, thank you very much for your time!