Zaharr was a belly dancer from San Francisco who escaped a convent school in Minnesota, named herself Zaharr, and made a pilgrimage to Haight-Ashbury in the mid-1960s, the epicenter of the counter-culture, to find her true self. What she found there was Beat poet Alan Ginsberg hosting traditional Japanese tea ceremonies that sometimes included LSD and psilocybin mushrooms. Thick foamy macha tea, Beat poetry, LSD, and a belly dancer feeling the moment. A pure reflection of the age and place in which they found themselves, it was all connected by a desire to understand and practice Zen Buddhism, made popular, even hip, by Alan Watts. The tea ceremony is a quintessential expression of Zen. Dig it, man.

I met Zaharr in Kyoto some 20 years later. She had been studying and practicing Zen in Japan the whole time. Zaharr is one of the finest dancers I have known, a goddess of curves and perfumed hair, cymbals and swirling fabric. Ambrosia. She didn’t “do” choreography. She was a Zen adept; feeling and expressing the moment was her thing. She understood Japanese classical aesthetics and Zen debate better than any other foreigner I knew. Living near several Zen monasteries, she delighted in verbal jousts with Zen monks, in which riddle-like conversations often distil into mere gesture. When Zaharr would offer a riposte to the monks in mere gesture, it was memorable.

Zaharr’s path to Buddhism is not so unusual for her generation of Americans. It was the Beat poet acid tea ceremony that brought her to Zen. A monk once asked her why she was drawn to Zen, and she cooed seductively, “Wu wei.” (non-action). She often quoted Watts to them: “Defining yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth.” I can’t think of the hippies, whom I admire so, without thinking of Eastern spirituality, drugs, and sex. Taoism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Zen; LSD, mushrooms, and pot; yoga, meditation, and tantric sex—all were rising together. There’s a reason I have been thinking of Zaharr.

Recently, I solved a 17-year-old riddle concerning dancing animal-headed deities I first saw in 2000 at the Avolokiteshvara Temple at Lamayuru Monastery in Ladakh. I had never seen such a field of enhaloed metaphysical beasts dancing as part of the progressive action of a large mural. I had seen a circle, or several wrathful deities on a thangka painting, but nothing like this. At the time a Nepalese Princess apologetically told me that she knew what they were but didn’t have the English to explain it. No monk there could offer insights. Some told me they were dharmapala, protectors of Buddhism. Whatever they were, they were brandishing implements and skullcaps of blood, wearing skins, and dancing up a storm.

About six months ago, I received an email from an Italian scholar practitioner, Kristin Blancke, who had also seen the incredible mural. But she knew what it was: a depiction of the Bardo Thodol, better known in the West as The Tibetan Book of the Dead. She initiated an online crowdsourcing appeal for anyone with images or information on the rare mural (one of only two I know of in the Tibetan religious world). The result is the largest known collection of images of the mural, spanning more than 25 years of ever-more-worrying physical damage. All of the images of that mural included in this three-part series come from that collection.

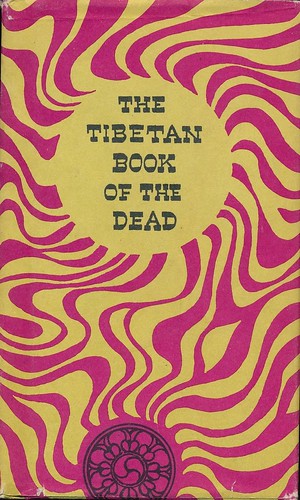

I have read The Tibetan Book of the Dead perhaps 10 times in different translations. The real translation of the name of this text is Liberation Upon Hearing in the Intermediate State, because it is intended to be read aloud to the dying and deceased person. Each version is insightful. It is always a trip. The Evans-Wentz translation is the original historical artifact and strange attractor, shaping discourse on the revealed afterlife yoga for a century, quite unattached to any critical Tibetan tradition. It was his idea to give it the sexy title The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which has stuck ever since.

Book of the Dead. 1965. From Core of Culture

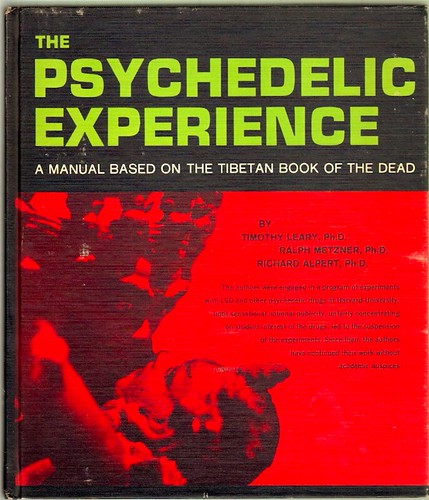

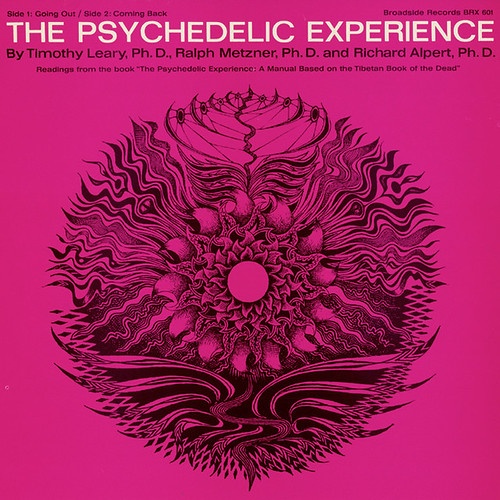

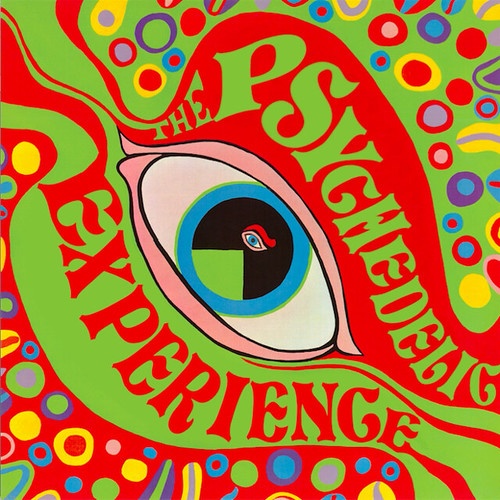

My research led me to a translation that I was previously unaware of: The Psychedelic Experience — A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, by Timothy Leary, Ph.D., Ralph Metzner, Ph.D., and Richard Alpert, Ph.D. Leary is the father of LSD experimentation, famously dying as planned, a last teaching. Richard Alpert is better known as Ram Dass, author of the hippie enlightenment classic, Be Here Now.

of the Dead, by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert.

University Books. Hyde Park , NY. 1964

Karl Jung and Lam Anagarika Govinda wrote the introduction and commentary to the third edition of Evan-Wentz’ Book of the Dead, so Western interpretations were already far out by the time the hippies read it. It had become a post-WW2 counter-culture standard before being adopted by the mind-altering beatniks. The lineage from Evans-Wentz, to Govinda, Jung, Huxley, Leary, Ram Dass, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Gysin, and Kerouac reads like a tribe that created new ways of life. I sit at the feet of Sublime Weirdos.

When I told my friends and colleagues with some thrill that I had come upon this Leary LSD-manual translation of the Book of the Dead, and asked had they heard of it, those who had lived through the 1960s were stunned at my ignorance. “It was in every bookstore in San Francisco, you could get it everywhere!” said a performer friend. “My husband and I dropped acid and did it in the ‘70s! Thanks for the PDF and the great memories,” said another.

Readings from the book “The Psychedelic Experience, A Manual based on The

Tibetan Book of the Dead.” by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert.

Broadside Records, 1966

A Scotsman who knew Leary personally reprimanded me: “Your classical education should have included the Psychedelic Classics: Be Here Now by Ram Dass, The Doors of Perception (and “Heaven and Hell”) and Island by Aldous Huxley, The Joyous Cosmology: Adventures in the Chemistry of Consciousness by Alan Watts, The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience by Robert Masters and Jean Houston, Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer by John Lilly, Naked Lunch by William Burroughs, The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac, Secret and Sublime by John Blofeld, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, and of course, Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert’s Psychedelic Experience, their LSD-manual version of the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Those are some of the era’s classics of consciousness exploration. What did they teach you?”

A curator colleague told me: “You can picture these as the literary equivalents of Peter Max’ Cosmic Jumper: a perfect expression of the expanding consciousness of that charged time.” Actually, I could see it all in Zaharr, too.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the Bardo Thodol, is a yoga or spiritual technique that originated with Guru Rinpoche, the founder of Tantric Buddhism, who left it for another generation in the form of a Ter, or Treasure, to be discovered by a Terton, or Treasure Revealer, a type of yogic saint with access to these teachings that cross time and space. It was the 14th century, and the Terton was Karma Lingpa, who had a visionary experience and consequently recorded it as a spiritual text. Painted images of the visions came later. Vision first, then written text, then vision depicted.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead is one of those rare superabundant spiritual masterpieces that blow the mind, like the I Ching, and the Book of Revelation. They are viewed in awe as oceans of cryptic, symbolic wisdom. More people talk about them than read them; make reference to them than understand them. They excite the imagination and emotions.

From a Tibetan standpoint, the Bardo Thodol is one part of a vast and ancient set of funeral rites. Even as a revealed Ter, it is part of a larger revealed Tantra of the Peaceful and Wrathful Deities. How it has taken on a life of its own is a fascinating tale. The point of using it in death is knowing it in life. Chod is a yoga in which the self is symbolically dismembered, the Bardo Thodol is a yoga where the psyche deconstructs. Both can be practiced throughout one’s life.

Intention of the Wrathful and Peaceful Deities, from which the Bardo Thodol is taken. It

depicts the 100 Wrathful and Peaceful Deities, corresponding to psychic components of mind

and heart. Dancing deities appear within the two upper concentric circles. 18th century, Tibet.

Image courtesy of the Rubin Museum of Art

Some Bardo artworks portend to show Karma Lingpa’s visions within the formal conventions of Tibetan painting, mandalas, and thangkas. Others try to show the characters of the Bardo Thodol in an instructive way to teach the process of the yoga, which can last up to 49 days after death, using initiation cards, scrolls, and murals. Dancing animal-headed deities appear in all.

The cast of characters that appear in the Bardo comprise the fundamental symbolic representation of the philosophical underpinnings of Vajrayana Buddhism, and so they also appear in painting and sculpture and dance outside of the Bardo context. The point of the Bardo Thodol is using the self-arising hallucinations, and so, perceiving the illusory nature of our minds, we see the true nature of reality.

Cham dance functions in part by bringing to life indelible deities that one will encounter in the Bardo state, and thereby recognize them as manifestations of one’s own intellect, be unafraid, and attain enlightenment. The ambush and glory of the after-death state is understood as visions. They are unreal. It is not difficult to see parallels with the hallucinatory psychedelic experience or meditation on the matter of illusory reality. It is about the mastery to pass through and benefit from this illusory experience.

The popularity of Leary’s book led a wave of interest in the Evans-Wentz translation, which, like Richard Wilhelm’s translation of the I Ching, became a household item and personal icon of the hippie era. The hippies were practitioners; adventurous, sensuous, and spiritually curious; attuned recipients of ancient metaphysical practices crossing centuries and continents. Turn on, tune in, drop out. It worked. They made history in the exploits of human consciousness, for whom the Bardo Thodol was the Ultimate Trip.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Tibetan Book of the Dead, Part Two: The Hour of Our Death

Tibetan Book of the Dead, Part Three: One Last Dance