Like many photographers, I was trained as a painter. I also did pottery and continue to study schools of Asian philosophy. I do not consider myself to be an ex-painter or a potter of yore, but rather an artist currently focusing on photography. In many ways, photography is less tactile than painting or pottery, but no less tangible. Photography, in the purest sense, is devoid of properties like other attributes which may characterize painting, such as impasto or pentimenti. Similarly, a photo cannot exhibit the same surface quality as that of a vessel created from, say, celadon glazed Koryo porcelain.

I find photography to be more analogous to pottery than painting. This similarity emanates in the transcendent fleeting “capture” of a transient moment, a moment that photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson termed a la sauvette or “decisive”. Clay on a turning wheel is as evanescent as the opening of a camera’s shutter. The photographic image appears at first dim but acquires a shining significance almost as an intelligent accident. The excitement of plunging the shutter while the photographer suspends critical thinking is comparable to the tapping of the subconscious as moist clay becomes a vessel.

Zen teachers always maintain that the answer to a koan is quite obvious while our inability to “see” the obvious is the point. Like a koan, a photograph asks a question to help us see, to awaken. What we wake from is the conjured thaumaturgy of “self presence” to develop an understanding of pratityasamutpada or dependent origination. If we view an image outside of our vernacular of everyday understanding, we will still engage in a conversation. How the conversation originates is dependent on what we see in the image. A viewer of a photograph may see a cow, while another viewer may see the non-cow, or pasture even if neither viewer has ever seen a cow or a pasture. We recognize that there is no persistent self which views the semiotics of a cow or the pasture but only the -ism of cowism and non-cowism.

People influenced by Western culture often ask for “photoshop favors”, for the photographer to removed their eyebags, wrinkles or second chin. They don’t really like their photo taken. Oscar Wilde observed, “The camera, you know, will never capture you. Photography, in my experience, has the miraculous power of transferring wine into water.” Indirectly supporting Wilde’s observation, is the photographer Annie Leibovitz: “I’m pretty used to people not liking having their picture taken. I mean, if you do like to have your picture taken, I worry about you.” In his Letters to Felice, Franz Kafka wrote:

“And who took the photograph? Is it some sort of family occasion? Your father and brother appear to be in dark suits, with white ties, but the so-called brother-in-law is wearing a coloured one. Dearest, how powerful one is, face to face with a picture, and how powerless in reality! I can easily imagine your whole family stepping aside and removing themselves, leaving you on your own, while I lean across the big table searching for your eyes, finding them, and dying of joy. Dearest, pictures are wonderful, pictures are indispensable, but they are torture as well.”

Buddhism does not have a deity and therefore is not a true religion but rather, like photography, a practice. The late John Blofeld, a Buddhist scholar and writer once told the story of how he first became attracted to Buddhism when he was young. One day, he spied a strange statue in shop in Brighton. Sussex and his curiosity was awakened. When he asked what it was, the shopkeeper kindly told him it was a statue of a Buddha. Although he could not afford to buy it then and there, he very much wanted to. For days he could not banish the image with its calm and peaceful expression from his mind.

Jean-Paul Sartre has noted that an image is a “consciousness of an object.” As soon as he was able to afford it Blofeld bought the statue which became his most treasured possession and which he kept with him always. Seeing that statue, was for him a turning-point in his life.

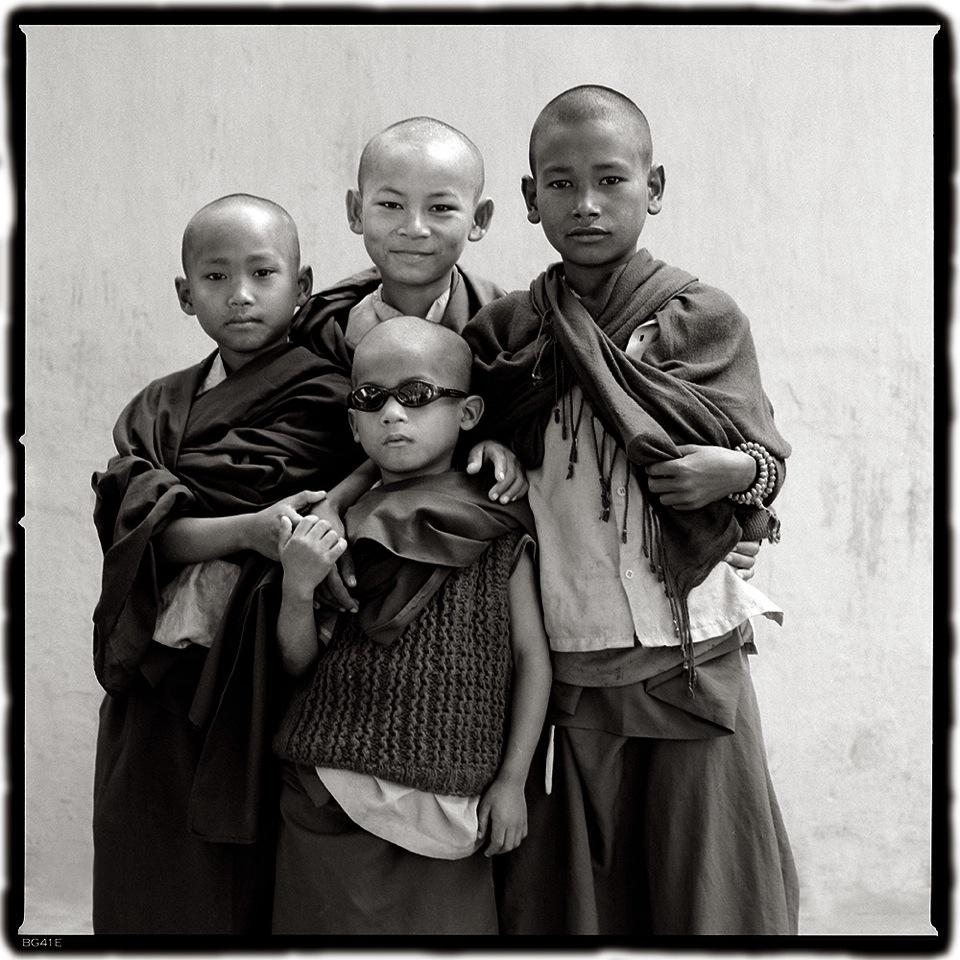

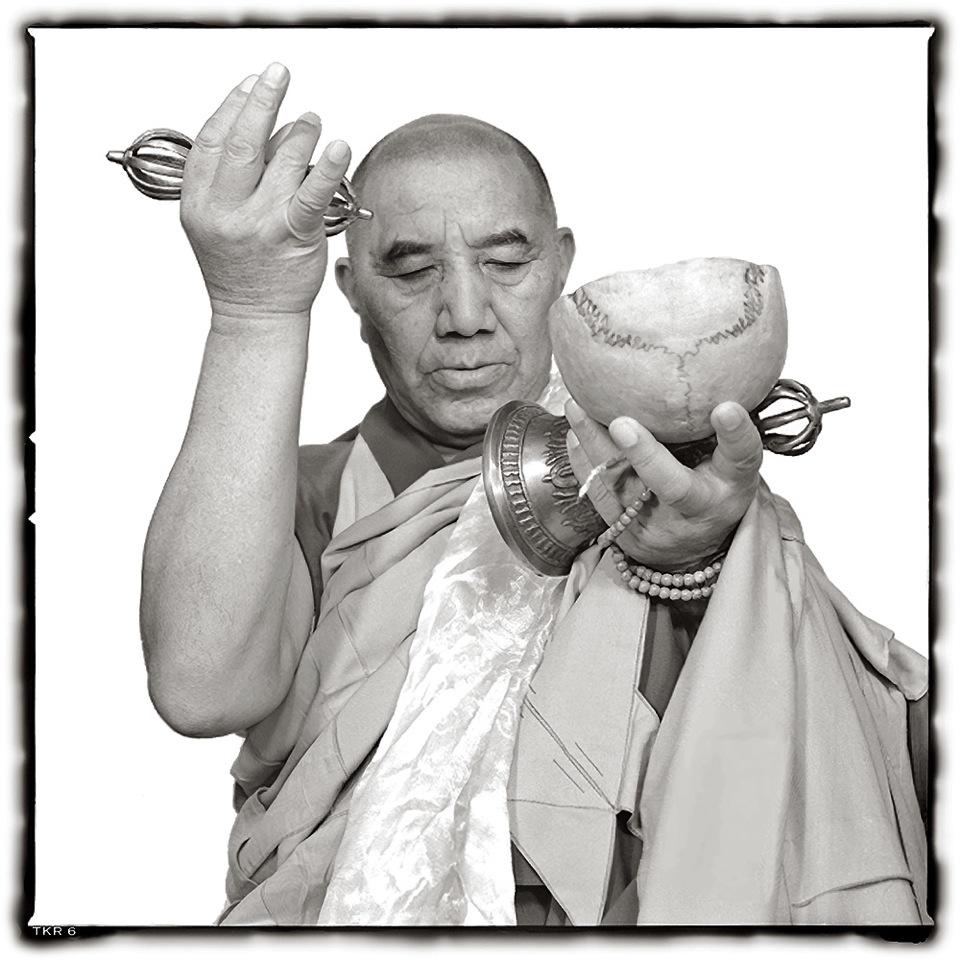

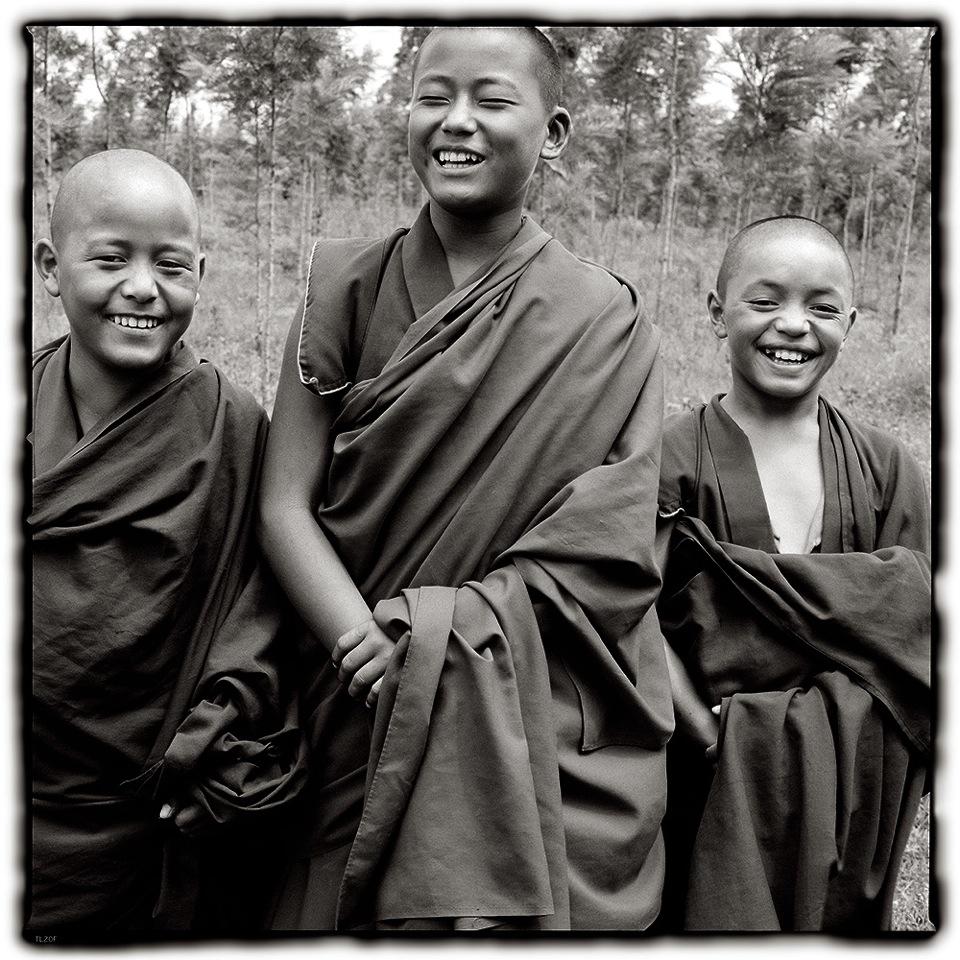

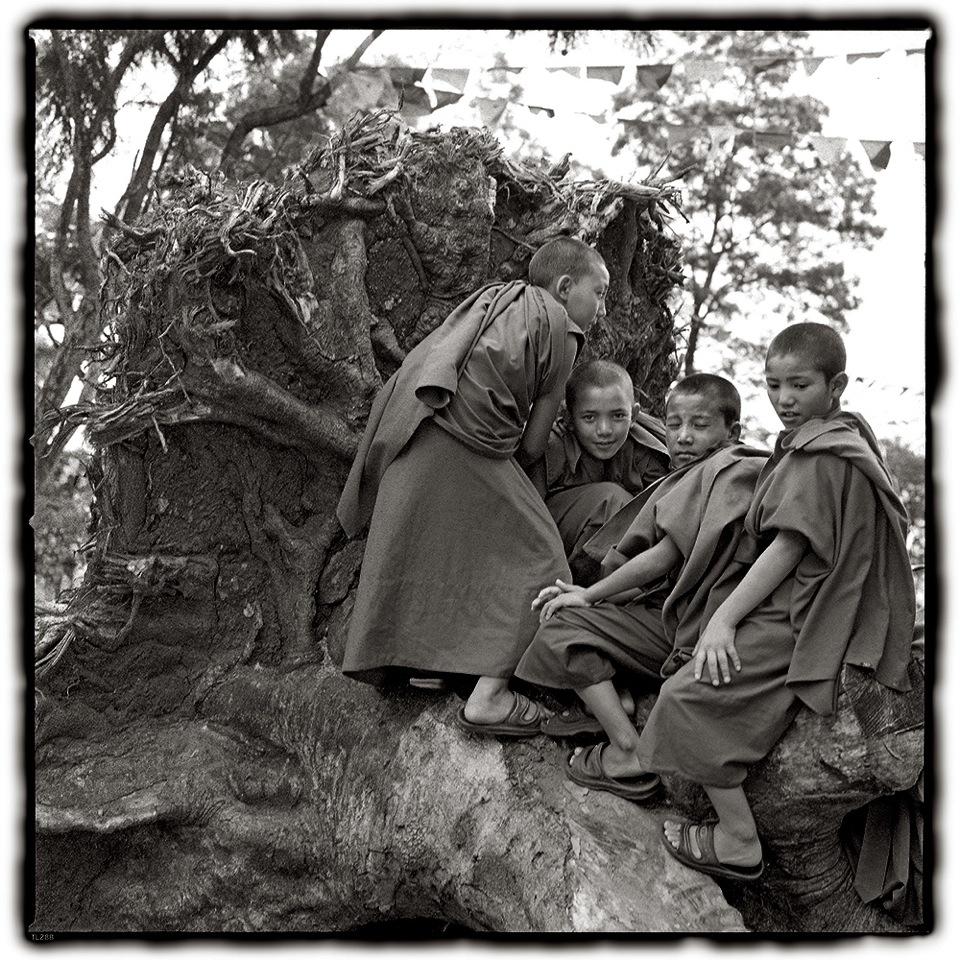

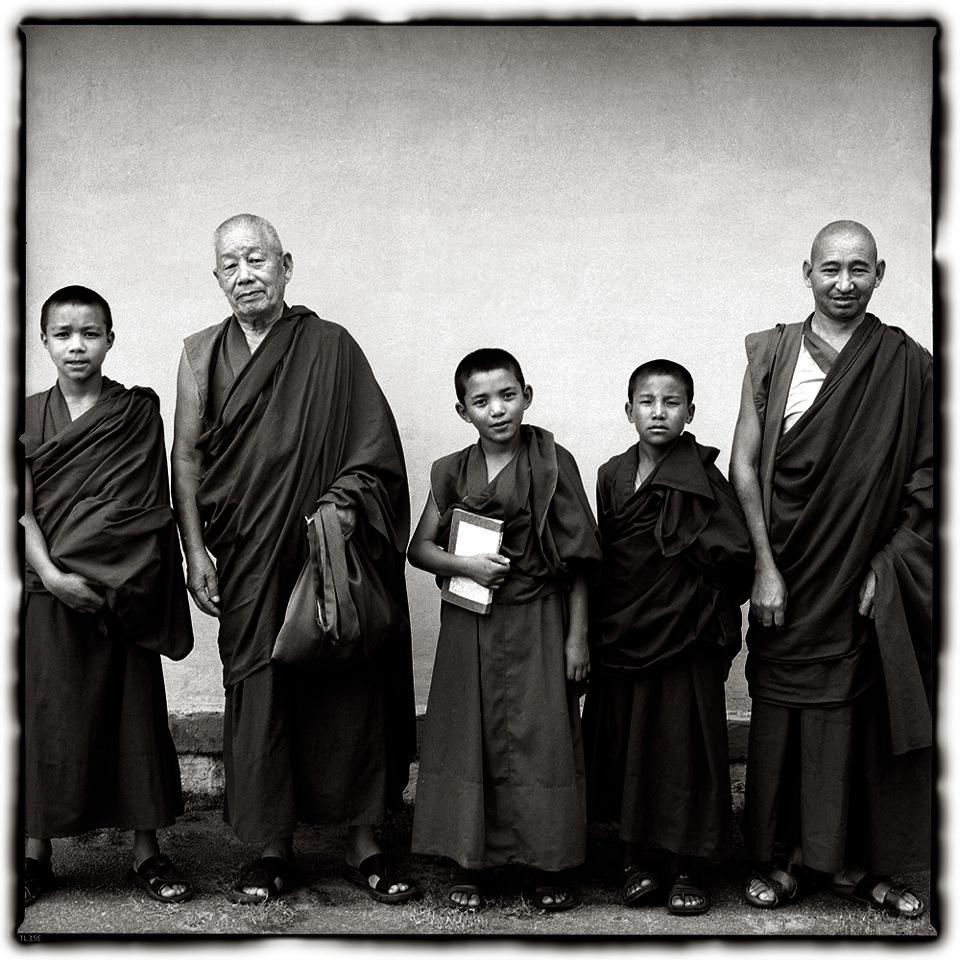

I have always considered Buddhism to be a cult of tranquility. In a photographic “text,” Buddhist monks radiate a tranquil narrative of what John Berger calls “quotations from actuality.” Tranquility may be a useful actuality of photography because it encourages spaciousness. Tranquility allows the viewer to sort out associations as they pertain to a photograph as terms of the imagination. My religion is Art, but I try to practice the tranquility found in Buddhism. My contemplative subjects suggest the form of unforced meditation which allows the mind to “empty” those memorable actions or gestures which provoke ideas to replay themselves as the shutter is engaged to make the subjects a recollected contemplative entity. As Minor White stated, “One should photograph objects, not only for what they are but for what else they are.”

A spiritual contemplative, monk or yogi, rarely feels their privacy invaded by the incursion of a camera. However, to get a good image, the photographer, via the camera, should also assume a meditative and respectful demeanor. If the subject of his lens can see her or his sincerity, then contemplation is freely transferred and, what Alfred Stieglitz termed the “equivalent,” is established. That, I think, is what photography is all about: a momentary connection, frozen in time, impermanent like always, but as close to a timeless bond as you will ever get.