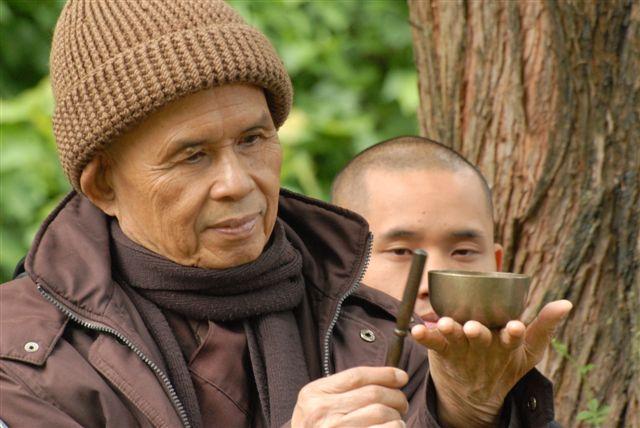

Throughout the life and ministry of Thich Nhat Hanh, one mission has remained more consistent in his thinking than even mindfulness: compassion. Long before he was travelling the world with his Order of Interbeing or WakeUp chapters, Thay was a monk-poet shaped and driven by the Vietnam War and the appalling physical and emotional scars left by that barbaric conflict. Before Thay was a speaker and retreat facilitator, he was a peace activist first and foremost, working tirelessly on the ground to save his people from being butchered, raped, or ignored by the rest of the world. He rubbed shoulders with Martin Luther King Jr and Thomas Merton, both of whom are symbols of the 20th century anti-war movement (and both also wrote essays in praise of their Buddhist colleague). The impetus was, and remains, compassion.

Doubtless, the world has become even more complex since the 1960s, and it is notable that among all those peace luminaries that represented an entire generation of activists, the elderly Thay is the only one that remains with us. But ultimately, it is fairer to conclude that mindfulness is a key component within Thay’s philosophy of compassion, rather than a philosophy in itself (even though it is easy to construe mindfulness as the central philosophical rubric. Mindfulness is the key that unlocks all doors to a more compassionate and loving life).

It is possible to go one step further and call this philosophy a theology of compassion. After several years of following his teachings, I believe only theology is a strong enough term to capture the thoroughly Buddhist, religious nature of Thay’s thought. Of course, Thay’s teaching has always been grounded in a Dharmic way of seeing the world. But by 2010, I began to notice an overtly theological side to his otherwise generic Mahayana philosophy. Mahayana thought cannot help but be theological in orientation, aligned as it is towards transcendent Buddhas like Amitabha.

As early as his 2006 book on Cultivating the Mind of Love he invoked the Buddha Vairocana of the Flower Ornament Scripture (Avatamsaka sutra) to highlight how one can heal the hurt left behind by the departure of a loved one. Then came his 2010 pocketbook The Energy of Prayer, and his theology has only grown more pronounced since, its influence suffusing practically all his poetry, books, and lectures. Below are only some brief windows that characterize this theology of compassion.

· Deep listening – Thay invokes Avalokita or Avalokiteshvara as the bodhisattva of deep, compassionate listening. This is a typical example of Thay’s creativity with Avalokita’s role as the Lord who looks down with compassion at the suffering of the world and his metamorphosis into Guan Yin, she who hears the cries of the world, in East Asia. Deep listening picks up not only what is said, but also what is not said. This theological approach to listening has transformed the way Buddhism-oriented counselling and therapy approaches suffering clients.

· Environmental awareness – Thay invokes Mother Earth consistently as a living, relevant reality to his students. This was quite clear from his Mindfulness Training programme’s approach to protecting plants and minerals, which is different from the usual formulation of ‘sentient beings’. Given the accelerating pace that the world’s resourced are being depleted, Thay has orientated his ecological discourse towards a notion of personhood for Mother Earth, speaking frequently of ‘healing’ her and ‘kissing’ her through walking meditation and other environmentally responsible ethical deeds.

· Spiritual freedom – Unlike Martin Luther King Jr or Thomas Merton, who both invoked the Kingdom of God over and against the worldly powers of oppression (and hence were deliberately political), Thich Nhat Hanh has rarely emphasised political freedom overtly. Be this a product of traditional Buddhist detachment from secular politics or the example of incarcerated monastics who meditated and possessed incredible strength and forgiveness, he has continued to use the language of liberation at a personal and communal level. No matter what the situation for the individual, real freedom is possible in the present moment.

· Everyday mindfulness – Even the mindfulness philosophy has been reshaped by the theology of compassion. Buddha is with us here and now, we don’t need to go to Vulture Peak to see him. The Kingdom of God or the Pure Land is here and now (he uses these terms interchangeably), in a characteristic appropriation of mindfulness discourse to two of the most important concepts in Pure Land Buddhism and Christianity. The origins of this relentless appropriation lie with his lineage in the Vietnamese Zen tradition, which is both devotional and practical in its application of meditation and everyday awareness. The Kingdom of God or the Pure Land is therefore present in each step we take, each morsel of food we chew, and each time we put on our clothes in the morning or brush our teeth.

· The four great bodhisattvas – Practice from the Heart invokes Avalokita (Avalokiteshvara), Manjushri, Samantabhadra, and Kshitigarbha in their respective realms of influence: listening, understanding, action, and support (2011 edition, 100 – 101).

It is helpful to remember how Thay began his long journey in Buddhism. As a child, he came across the issue cover of a Buddhist magazine, on which was a meditating Buddha, smiling and tranquil. If only he could experience a similar joy, he wondered – a theological aspiration to the core. It would set him on a path that would change his life and the lives of thousands across the world.His most important contribution in the 20th century, apart from the establishment of Plum Village, was to popularize the term ‘engaged Buddhism’. His most significant achievement in the 21st has been to reinterpret the ancient Five Precepts in light of contemporary concerns as the Five Mindfulness Trainings. But this theological feat, which is an intimate part of his compassionate theology, is a story for another day.

Related links

Order of Interbeing website

WakeUp!

Back to Plum Village Schools and Educators’ Retreat, April 2013 special edition homepage