In keeping with the theme of wrathful deities so prevalent in this series of articles, I decided to next discuss the gate guardians, known as kongо̄rikishi or niо̄, which stand on either side of the entrance gates to Buddhist temples, appropriately called the niо̄mon. The guardians, also known as the Two Benevolent Kings, often hold kongо̄ (Skt: vajra) — stylized lightning bolts wielded by deities as tools and weapons. Indeed, their Japanese name derives from the Sanskrit Vajradharas, which means “Wielders of the Vajra” or “Holders of the Thunderbolt”, and refers to their role as a split emanation of Shukongо̄shin, in turn an epithet of the vajra-wielding esoteric Buddhist deity Vajrapani. In their fearsome postures with angered expressions, they embody both latent and active violence against those who might threaten the solemnity and serenity of the Buddhist community.

There are varying theories on the origins of Shukongо̄shin, and the niо̄ as his emanations. The most common among scholars is that the deity Vajrapani had once acted as a protector for the historical Buddha Sakyamuni. Some of the earliest depictions of Vajrapani in the sculptural traditions of Gandhara (modern-day north Pakistan and Afghanistan) show him in a bodyguard role alongside Sakyamuni. Vajrapani is believed to have been modeled after the Greek god Heracles, as Buddhist iconography from Gandhara was influenced by imagery transmitted from Greek, Bactrian, and Macedonian states along trade routes. In some cases, Heracles and Vajrapani are all but completely indistinguishable; Vajrapani even carries a club similar to that wielded by the Greek god. The club as a war-like implement is also wielded by one or both of the niо̄. Since Vajrapani, Shukongо̄shin, and the niо̄ are all “thunderbolt wielders”, there is some speculation among scholars whether the Greek influence might instead be of Zeus.

Another theory is that Shukongо̄shin derives from Devadatta, the disciple cum nemesis of the historical Buddha. While still on good terms with his cousin Sakyamuni, Devadatta acted as his impulsive yet well-intended bodyguard, often using a club or large stick to chase off would-be thieves or userers during their travels. Since Devadatta would eventually make attempts on Sakyamuni’s life — by assassin, by rampaging elephant, and by boulder — many think this to be an argument against the theory; though others counter that the historical Buddha himself prophesied that Devadatta would eventually attain Buddhahood.

Also relevant to the discussion of the niо̄ is the Indian concept of the dvarapalas. These fierce, brutish creatures were placed at the entrances of Hindu or Buddhist temples and could appear in the singular, if space was limited, but more commonly in pairs. Their countenance was likely influenced by the yaksas, powerful spirits of a protective nature, and by tutelary deities such as Acala. In fact, the Hindu deity Indra — notable for his weaponized thunderbolt — has origins as a gate guardian yaksa, and it is Indra’s thunderbolt which had been stylized into the single- or multi-pronged vajra implements. The niо̄ pairing was likely influenced by the use of dvarapalas in India and Southeast Asia; the esoteric patriarch Amoghavajra, whose translations of scriptures and commentaries were transmitted to Japan by way of Huiguo and Kūkai, traveled extensively through India, Southeast Asia, and Sri Lanka.

While representations of Shukongо̄shin do exist in Japan, they are quite rare. The 9th century “Collection of Japanese Buddhist Tales” and the 15th century handscroll Shukongо̄shi engi emaki are generally accepted to discuss the legends associated with an 8th century clay sculpture of the deity in the Hokkedо̄ at Tо̄daiji. According to the legends, Shukongо̄shin himself assisted the priest Rо̄ben (Japan, 689-773), the second patriarch of the Kegon branch of Japanese Buddhism, in the construction of Tо̄daiji. The image shows the deity in a dynamic stance, holding a single-pronged kongо̄ over his shoulder as if to smite the wicked who seek to destroy what he helped build.

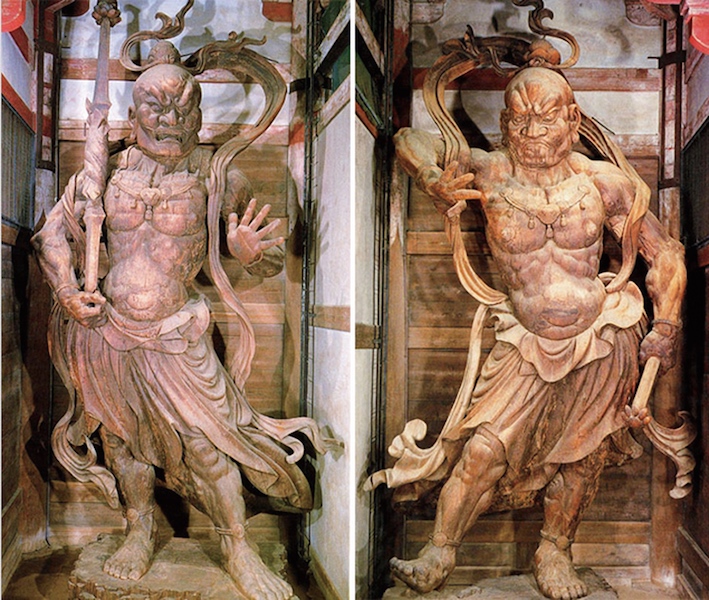

The niо̄, as extensions and executors of Shukongо̄shin’s role, are also counted among the ten-bu —Hindu deities who were converted to be servants and defenders of the buddhas and their cosmos. As such, they are mortal beings and thus subject to the cycle of rebirth, though their lifespans greatly exceed that of humans. In addition to the weapons which identify them as warrior deities, the niо̄ are often dressed in armor covering their entire bodies or only from their waists down. In the latter case, their bared torsos are lean and tautly muscled. In addition to their collective titles, they are individually named: the one who stands to the left side of the entrance, with mouth agape, is named Misshaku or Agyо̄; the other, with lips pressed together, is named Naraen or Ungyо̄. The sounds suggested by the shapes of their mouths — “Ah” and “Un” — assures the Buddhist adherent that the niо̄ will protect them against all things, from the heavens to the hells, from the beginning of time to the end of all things.

The oldest extant example of the niо̄ in Japanese art can be seen in a copper panel at Hasedera, which dates back to the late 7th century. As gate guardians, the earliest sculptural representation are the clay sculptures produced in 711 which stand to either side of the Chūmon at Hо̄ryūji. The most imposing depictions, completed by master sculptors Unkei and Kaikei in 1203, stand perpetual guard over the Nandaimon at Tо̄daiji.