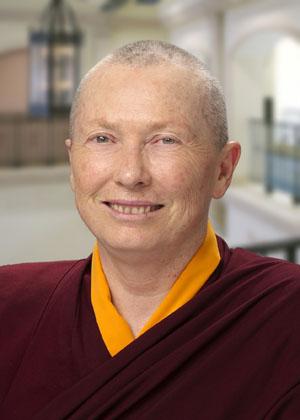

Editor’s note: Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo is the Branch and Chapter Coordinator of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women. In this series of seven questions we presented to her, she reflects on some key issues about Buddhist women and the long road ahead.

B: Our interest has always been how Buddhism can empower and transform women, and how women can in turn empower and transform Buddhism. I want to see this virtuous cycle happen because I can see that many old institutions – once run exclusively for men, most of them still run by men – need a fresh voice that can actually bring people back to Buddhism again and grow all three traditions. Do you think this is still a fair charge to make, or are we seeing genuine if slow progress across the board?

KLT: Change is gradually happening, but Buddhist institutes are still run almost run exclusively by men. As an ancient tradition struggling to survive under very different social conditions and faced by intensive conversion attempts in many countries, Buddhism needs to utilize all of its human resources, especially women. Overall, women have proven themselves to be competent, honest, and enthusiastic about preserving Buddhist traditions, though their contributions have rarely been acknowledged.

For meeting the challenges of modern society, fresh ideas and new voices are essential. Women in traditionally Buddhist societies are very devout, hardworking, and dedicated to the Dharma. They need greater access to systematic Buddhist education to prepare them for more active and visible roles. When we look at women’s achievements in education, law, medicine, business, and other fields, we see that women have the potential to excel in every field. Only in the fields of religion and politics are women being held back, and human society is the poorer for it. Buddhists who truly care about social transformation and spiritual development can no longer ignore women’s potential to contribute greatly to the flourishing of the Dharma.

Great changes are afoot. Progress has occurred very swiftly in Sri Lanka, thanks to the supportive attitudes of a few monks. This has allowed Sri Lankan women to move ahead in the directions of intensive meditation practice and full ordination. Progress is also occurring in the Tibetan tradition, primarily in the field of education. There has been no progress in the direction of full ordination, but nuns are gaining confidence and are beginning to find their voice. In other countries, however, especially Laos and Cambodia, Buddhist women have made little progress, primarily due to political circumstances and poverty.

I believe there’s a great need to develop a global perspective that understands the needs, challenges, and special abilities of Buddhist nuns in different societies. If Buddhists in more affluent countries understand the serious problems that Buddhists in less fortunate countries face, hopefully they will generate compassion and find ways to help their Buddhist sisters and brothers, especially sisters. When Buddhists from affluent countries go on pilgrimages, they donate generously to monks and monks’ projects, but rarely do they visit or even know about or care about Buddhist women’s projects. The image of the saffron-robed monk has a very powerful allure in the minds of most Buddhists. This image is almost always male and, as a result, financial support and encouragement flow almost exclusively to male monastics. With such unequal support for monks and nuns, the disparities between the circumstances of male and female monastics grows increasingly acute with each passing year. In fact, monks’ monasteries with lavish support have seen a decline in ethical standards, which has caused considerable disillusionment in the lay Buddhist community. So, ironically, the generous support that many lay Buddhists give has in some cases contributed to corruption in the sangha and has also exacerbated gender disparities. In secular society throughout the world, gender equity is the buzzword. But in Buddhist circles, conference speakers and institutional heads remain almost exclusively male. This syndrome works to disadvantage women. In view of the current global ethic of gender equality, some Buddhist societies appear extremely backward. We find a great contrast between Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam and increasingly China, where Buddhist nuns enjoy educational opportunities and strong lay support, and poorer countries without full ordination, where women are making very little progress. The contrast appears to turn on access to full ordination for women.

B: 2013 saw the Assocation’s 13th conference. Was there anything different about it from the previous twelve (thematically, demographically, etc.)?

KLT. The theme “Buddhism at the Grassroots” focused attention on the living circumstances and current projects of Buddhist women in many different countries. With participants from 32 countries, we had wide representation from Buddhists of different communities and had a chance to get updates on the wonderful work that Buddhist women are doing around the world. For the first time, we had participants from Turkey and Estonia. Again this time, we had large delegations from China and, for the first time, we learned about some of the amazing projects that are underway for Buddhist women in various parts of China. Bhiksuni Guo Xuan from Xian estimated that there are currently 80 000 bhikkhunis in China, more than the number of bhikkhunis in Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and other countries combined.

Workshops in the afternoons again allowed participants to share ideas on a one-to-one level, with women speaking from their own experience. Located in India, the conference had a large number of local participants, especially from Maharashtra and various Himalayan regions. For the first time we had speakers from Sikkhim and Arunachal Pradesh. This conference was unique in including a number of video presentations on topics as diverse as the roots of gender discrimination, the lives of Korean nuns, and the work of B. R. Ambedkar for the advancement of women and the lower castes. The conference made an environmental statement by not using plastic bottles, showing Buddhist women’s concern for the environment on a grassroots level.

Perhaps more than any other conference, we were able to offer accommodations for a wide range of budgets. And we were able to offer a selection of cuisines, including Indian and Vietnamese.

Workshops and performances by the Tara Dancers afforded insight into contemporary Buddhist creative expressions. The pilgrimage tour following the conference was a very special opportunity for Buddhist women from around the world to visit Buddhist sacred sites to join their prayers and to express their common aspirations.

B: How is the future of women’s participation in Buddhism looking, judging from the results of this year’s conference? Certainly it varies region by region: which are the hotspots where development for Buddhist women is urgently needed?

KLT: The future prospects for Buddhist women’s development are excellent, if they get support during the crucial initial stages. Judging from this year’s conference, Buddhist women are becoming increasingly active working in their own localities and are linking up to support one another like never before. These international links provide vital inspiration, encouragement, and resources. The needs of Buddhist women in each country are different, however, which makes Sakyadhita all the more interesting.

While Buddhist women in Europe and North America are working on issues such as sexual harassment, greater representation in the U.N. and other international forums, historical research, textual analysis, including feminist analysis, and representations of women in Buddhist texts and institutions. Buddhist women in developing countries are vitally concerned with basic issues such as health, hygiene, access to Buddhist learning and practice, and training opportunities, including both monastic training and vocational training. In some areas, such as Buddhist psychology and meditation, they find common ground, which is very inspiring and empowering. Sakyadhita works to better understand the needs that Buddhist women are grappling with on the ground and to figure out ways to serve these diverse needs.

The international partnerships forged through Sakyadhita are extremely meaningful for women, many of whom have felt isolated, alienated, and discouraged. We want to address the most urgent needs first, such as the trafficking of Buddhist women and children, which are rife but often ignored, and healthcare, especially for women infected with HIV/Aids. At the same time, we realize that women need to follow their own dreams and passions, which may mean working on the basic issues of survival that are specific to their own communities.

Sakyadhita’s international conferences make women aware of new directions that need attention and methods that have proved successful in other countries. For example, women may begin to realize the lack of Buddhist education for children or the lack of prison Dharma projects in their own traditions or localities and become inspired by the work of other women to initiate them. By expanding their vision of what is possible, Buddhist women can determine their own priorities. The potential for Buddhist women’s social activism is immeasurable, limited only by a lack of qualified human resources and financial support.

B: How involved are traditional Buddhist organizations and foundations with Sakyadhita? In general, do they recognize women’s critical role in the future Buddhism, or do most still seem to resist any calls for change or reform?

KLT: Most Buddhists seem to totally ignore women’s issues and women’s roles. Most traditional organizations are not involved at all. Most Buddhists seem unaware of the critical role women can play and do not seem to care about women’s disadvantaged status. Buddhists seem to believe their own propaganda that women and men are equal in Buddhism, and are blinded to the blatant inequalities that currently exist. Some Buddhists pay lip service to women’s importance, but institutional structures do not reflect any commitment to women’s advancement or to women’s equal participation. In fact, the mantra that women and men are equal in Buddhism acts as a kind of smokescreen to mask inequities that are clearly visible. Women continue to be sidelined in public forums, even by educated and otherwise compassionate people, both women and men.

When traditional institutions acknowledge the importance of women at all, they often do this by consigning women to traditional roles within archaic structures and praising women for staying in those roles. If they enlarge women’s roles, for example, by allowing women to teach or to occupy an administrative role, they do so without really reforming the organizational structures and ethos of their organizations to give women autonomy, independence, and leadership opportunities.

In response to a growing awareness of the need for more equal representation of women in Buddhism, women, especially female monastics, may be pressured to step into teaching and leadership roles before they are fully grounded and trained. Instead of nurturing women’s leadership or giving nuns the chance to get solid training and education, they may be thrust into positions of authority and pressured to teach and provide leadership without the preparation that their more privileged brothers get. Occasionally, in an effort to be politically correct, a woman may be thrust into a public role, ignoring the fact that leadership requires preparation, education, and experience. “Buddhism at the Grassroots” means preparing women from the ground up, by providing the causes and conditions for successful leadership: systematic education, health care, training, and experience, so that women will be fully qualified to take leadership roles. Buddhists urgently need qualified people to represent Buddhism in public discourse and it is impossible to speak with authority unless one has adequate preparation and encouragement. All of this requires resources that Buddhist women in most countries do not have. So, we are stuck in a bit of a Catch 22. We need support to nurture Buddhist women leaders and we need Buddhist women leaders to help garner this support. The most crucial phase is when women are first starting out and struggling; once they are published and internationally acclaimed, support comes naturally.

B: How can Buddhist feminist groups mobilize effectively? Many already look to the grassroots organization of Sakyadhita as a model. Are there any variables that an individual organization needs to factor in, such as the region they are based in or their level of funding?

KLT: Sakyadhita encourages the establishment of grassroots Buddhist feminist groups. Sakyadhita itself has established national branches in a number of countries and has active local chapters who meet for discussion groups, Buddhist study groups, and various projects. These groups are all limited by the lack of financial support and could do much more if more resources were available. What is encouraging is a growing awareness that feminism is not a pejorative term and that Buddhist feminism is simply a compassionate response to blatant gender discrimination that urgently needs repair. We hope that women will be encouraged to gather more frequently on a grassroots level and find the tools they need to increase gender awareness in Buddhist societies.Women in different regions have different interests and concerns, determined by their circumstances. The immediate concern for women in most of Asia is how women can learn more about Buddhism, since Buddhist institutes for women are few and far between. Building Buddhist institutes requires enormous resources and skills that most Buddhist women do not have – educational resources, organizational skills, communication skills, and so on. Buddhist women’s projects are very much dependent on the scarce resources that are available to them. There’s a lot of catching up to do before Buddhist women in disadvantaged communities will be able to make big strides forward. As long as Buddhist nuns are barely scraping, why would intelligent young women want to pursue a career as a nun? By contrast, Buddhist women’s projects in more advantaged societies have resources to run kindergartens, shelters, retreats, schools, and other endeavors, some of which generate further resources and enable women to move toward self-sufficiency. In these societies, Buddhist women have an impressive track record and great potential for future achievements.

B: One of the conference topics was “Is there a Feminine Dharma?”. This question is far more loaded than the usual question about nuns or laywomen. It assumes that the Dharma has a feminine aspect, and any conception of Dharma as having any gendered aspect might seem perplexing to an orthodox vision. Can you elaborate more about this?

KLT: The question “Is there a feminine Dharma?” is loaded, but it’s worth exploring. Do women and men approach Buddhist practice differently? The papers presented on this topic made it clear that Dharma practice and attainments are open to all, regardless of gender. The basic nature of the mind is not different for men and for women. The potential to purify the mind is not different for men and for women, at least in theory. But it was also clear from the ensuing discussions that the circumstances for realizing the human potential for enlightenment are very different for men and for women. Women still do most of the work in their homes and fields, and have greater household responsibilities, and generally have less time for formal Dharma practice. Women have far fewer opportunities for Buddhist education and training, so their potential for liberation is clearly circumscribed. How can women get access to the tools for liberation – the instructions and conditions for practicing on the path – if they cannot read, have no books, have no access to teachers, if teachers are not free to teach women, if their work schedules and domestic duties leave them little time for learning about the Dharma? How can women realize their potential for awakening if they do not have equal access to monastic life? How can they develop the confidence to strive for liberation if they are taught from early childhood that the very body they occupy is a result of their bad karma? How can somen gain the confidence they need to strive diligently when their teachers say that women’s path to higher ordination is blocked? These are the challenges that Buddhist women face today.

All of these problems can be remedied fairly easily, if there is greater awareness and the will to do so. If women approach the understanding of Dharma differently and forge new approaches to practice, this may be a strength. At the conference in Vaishali, the Tara Dancers illustrated this in their innovative and empowering approach to learning Dharma through movement. Given equal education and opportunity, it is likely that women will contribute fresh insights, including practical ways of integrating Dharma in daily life, for example, the ethical development of children, healthy approaches to caregiving, and compassionate means of social service. Women can help expand the concept of intensive practice beyond the monastic limits imposed by certain traditions, providing greater affirmation of lay practice. Women may put their communications skills to work, developing new, more accessible ways of expressing the Dharma. They may put their organizational skills to work, developing more egalitarian structures for Buddhist and other institutions.

B: Women obviously have so much to give to this ancient tradition. The more awkward question is, does Buddhism have anything to offer women?

KLT: Certainly Buddhism has much to offer women, especially psychologically and spiritually. Starting from earliest Buddhist times, as evident in the Therigatha (Verses of Elder Nuns), Buddhist insights into the nature of the mind and correctives for mental defilements have been seen as spiritually liberating for women. Historically, too, Buddhism has been socially liberating for women, giving women the rights to divorce, remarry, and monastic life, which have translated to considerable social freedom. Pre-existing social constraints on women have not been completely overcome, but gender inequalities and other social ills cannot be laid entirely at the feet of Buddhism. Of course, it is regrettable that Buddhism picked up patriarchal, even misogynistic elements from pre-existing social and cultural mores and has not been successful in eradicating them. Attitudes towards women, although better than in certain other societies, are still not 100% egalitarian and these attitudes, especially when internalized by women themselves, have held women back. But all these obstacles can be overcome through education and by applying the essential Buddhist teachings in an egalitarian, socially liberating way. Concepts such as no-self and universal compassion are ready resources that can be utilized for empowering women and for cutting through sexist preconceptions about women. The Buddha’s teachings are essential tools for understanding mental defilements, such as fixed concepts of the self, that are the root causes of self-centeredness and discrimination. If we put these teachings into practice, we can liberate ourselves from constricting, unpleasant habits such as sexism and other forms of discrimination. Based on their first-hand experience of discrimination, women can empathize with others who experience discrimination and pave new pathways for freeing the mind from these disagreeable habits.