‘Listen,

O brothers and sisters,

you who have mastered the teaching –

If you recognize me,

Queen of the Lake of Awareness,

who encompasses

both emptiness and form,

Know that I live in the minds

of all beings who live.’

– Yeshe Tosgyel, The Inner Journey: Views from the Buddhist Tradition, 244.

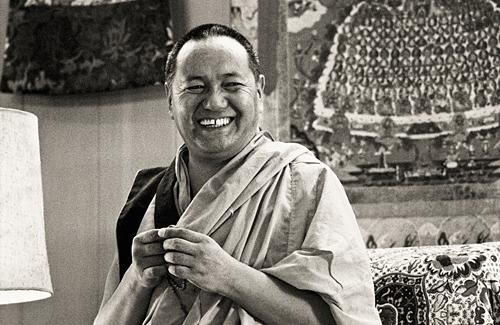

The prologue to Lama Yeshe’s (1935 – 84) The Tantric Mudra for Everyday Life observes: ‘Here [in this book]… we will not be trying to understand the various philosophical points of view or to develop a merely intellectual understanding of mahamudra. We will try to achieve a direct experience of it’. He further insists: ‘The intellectual world and the practical, experiential learning process are as different as a supermarket and Mount Everest. If you leave mahamudra at the intellectual level, it will never touch you; it will have nothing to do with you’ (21).

In case Lama Yeshe’s hint isn’t clear enough, the emphasis is categorically on the application of mahamudra, not just banging on about it as armchair philosophers.

This is only one example in many of the unity between theory and practice in the name of realizing a fabled state of mind. Modern Tibetan Buddhist masters have very keenly tied together centuries-old Tantric doctrines with a hardheaded approach to teaching modern practitioners the realistic benefits of their practice. The argument about the influence of results-oriented Westerners may be valid, and certainly has had some effect on the teaching styles of many Tibetan teachers. Yet the philosophical debate about these two wings of ‘theory and practice’ has a long history. From Indian forebears like Shantarakshita to native Tibetan commentators, there are few more persistent debates in the Indo-Tibetan tradition.

Few have dedicated so much time and cerebral firepower to the history of this dichotomy than Professor Dorji Wangchuk of Hamburg University. In his recent paper for the Meditative Praxis conference at The University of Hong Kong, he tried to discuss the general historical relationship between philosophical theory and spiritual praxis in Buddhism. He also explored the doctrinal relationship between the two ‘wings’ based on Indo-Tibetan Buddhist sources. The full story is incomplete, for his paper has yet to be released in a future publication. But we’re still empowered to identify some clear contours in this great and winding beast.

The first issue of the historical relationship involves the question of how philosophical theories and spiritual practices developed diachronically. Here, Prof. Wangchuk was interested in whether Buddhist philosophical theories developed out of certain spiritual practices or whether spiritual practices evolved out of philosophical theories.

The second issue of the doctrinal relationship between philosophical theory and spiritual praxis ‘concerns the question as to how they relate to each other synchronically in any given point in time’. How do the two ideally synchronize and harmonize? How did Indo-Tibetan masters, and their heirs today, see the mutual growth between deepened practice and heightened knowledge?

In the very specific case of Tantric smirtyupasthana (satipatthana) practice, Prof. Wangchuk believes it to have undergone changes under the influence of its philosophical theories:

‘The Vajrayanic practice of smirtyupasthana seems to have undergone modifications under the influence of its philosophical theories (e.g. the theory that all phenomena are intrinsically pure). Our ordinary body, for example, is no longer meditated upon (according to the Vajrayana) as disgusting (as in early form of Buddhism) but rather as empty (as in non-Tantric Mahayana) and pure.’

Based on this observation, it would seem possible to infer that specific theories, such as of emptiness, luminosity, and Buddha Nature were critical to shaping certain practices that are characteristic of Mahayana and later Mantrayana traditions. In other words, the idea that each of us have Buddha Nature innately present in us might have influenced in shaping the Buddhist Tantric of ‘taking the goal as the path’.

This synergy of teachings as truth holds true for the Nyingma school, which upholds its teachings as the ‘oldest’ of the modern great four Buddhist schools in Tibet. Even the Nyingma attitude to its own doctrines seems to affirm the way theory and doctrines change the living practice and self-perception of an entire faith community:

“I am not quite sure if the rNying-ma school would indeed claim that it, in its current form, already existed during the Early Diffusion. It is, however, true that a tradition tends to believe that its doctrines or scriptures that we know today have been there from the very outset. In reality, however, a doctrine or scripture – just like a person – would have a long complicated history of inception, transmission, dissemination, and reception. What a researcher attempts to do is to understand and explain this history. Such explanations normally would have no bearing on actual practices or practitioners.”

While academics have been keen to point out that the earthshaking schisms in Buddhist history were Vinaya-based and predicated on monastic lifestyle choices, perhaps the role of doctrine in shaping the life-worlds and practices of Mahayana and Mantrayana is growing more distinct with Prof. Wangchuk’s help.

Lama Yeshe wrote, in Becoming Your Own Therapist, that the study of Buddhism isn’t ‘a sceptical analysis of some religious, philosophical doctrine’ (35). He obviously hoped to emphasize the practical side of the tradition – honesty, self-examination, inquiry, and discipline. But perhaps there was a twinkle in his eye when he wrote that, for he could have just as easily written that Buddhism is a faithful practice of an accepted religious doctrine.

Back to the Meditative Praxis Interviews homepage