I recently attended a fundraising event for the homeless and it made me question—not for the first time—the value of what I do for a living. I am an art historian and I specialize in the arts of Asia. I teach at museums and at college-level classes, I curate exhibitions and I write books and articles—such as this Buddhist Art column for Buddhistdoor Global. I truly enjoy what I do and feel lucky to be able to spend my life exploring and sharing the artistic creations of people from diverse cultures, rather than struggling with a job that I find physically strenuous or intellectually tedious.

However, I know many people—lawyers, doctors, physical therapists, and social workers—whose work very obviously helps other people, and these people also enjoy their work. In comparison with them, I often wonder how learning, teaching, and writing about art is a helpful profession. On those days, I remind myself of the words of the Japanese Buddhist priest Kukai (or Kobo Daishi) (774–835): “Art is what reveals to us the state of perfection.”

Image courtesy of the collection of Scripps College, Claremont, CA.

Kukai was a man of many skills. He worked for years as a civil servant, a scholar, a calligrapher, a poet, and an engineer, and traveled to China to study Buddhism. He brought esoteric Buddhist practices from China to Japan and founded the Shingon school. As a scholar of this esoteric form of Buddhism, he understood and taught the transformative power of art. He not only read sacred Buddhist texts and conducted rituals using sacred chants (mantras) and hand gestures (mudras), Kukai also taught his followers to practice meditation and visualization using spectacular Buddhist paintings showing deities in their sacred palace realms (mandalas). These paintings, rich in color and pattern and skillfully painted following strict stylistic and iconometric rules, served to draw practitioners deep into the imagined realm of the deity so that they could transcend their emotional and material selves in order to attain enlightenment. This is the “state of perfection” to which Kukai referred, and works of art played a critical role in the spiritual transformation that made this state possible.

Private collection. Image courtesy of the author

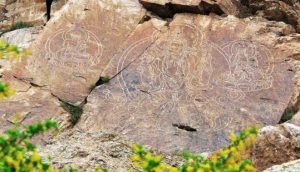

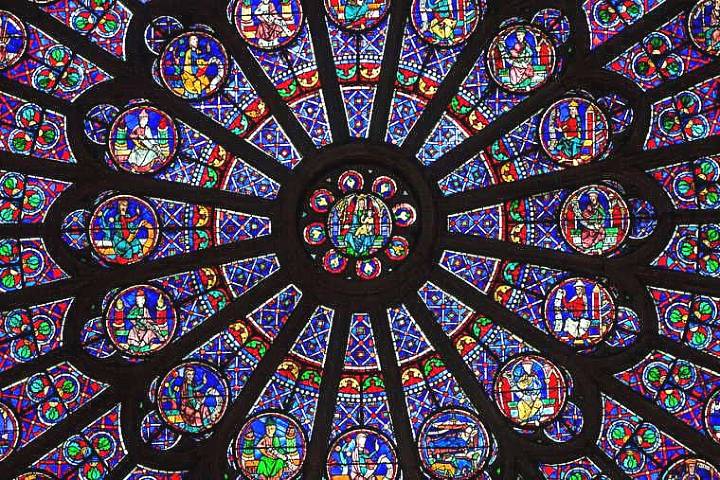

The religious arts (visual, musical, and performing) of most cultures serve a similar purpose of elevating the spirits of devotees so that they come closer to the focus of their worship. In most traditions, these arts are similarly born from such a high level of skill, tradition, and spiritual devotion that they are capable of moving followers emotionally and spiritually into an awakening of sorts. Walking through a medieval European cathedral, looking up at a pyramid in Egypt or Mexico, or gazing at finely carved Yoruba mask or an Australian Aboriginal Dreaming, one can feel a sense of sacred perfection—more than just awe at the artist’s technical skill, but a sense that perhaps something beyond human—possibly divine—caused it to be created.

Admittedly, many of the world’s religious institutions have possessed the wealth to hire the finest artists, artisans, and architects to produce their most important paintings, statues, buildings, and other expressions of religious faith. However, coupled with the level of the artists’ skill is their desire to create something outstanding enough to be a supreme expression of their devotion and one worthy of the gods. In their own acts of creative growth and reaching for perfection, these artists have come as close as they can to a god-like state themselves. And in front of their work, even non-believers can be moved by the spiritual force of their art.

I have sensed this stirring of my own spirit on many occasions: when staring up at the perfectly positioned colors of a stain glass window, or viewing the exquisitely fluid lines of Arabic calligraphy in an ornate copy of the Q’uran, or beholding the elegantly balanced face of the seated Buddha at the Byodoin temple. I have had a similar feeling in front of secular art too. I have felt myself pulled into a painting by Van Gogh or stopped in my tracks by a small ceramic tea bowl. Sometimes my reaction is entirely visceral—a response to an aesthetic quality in the artwork or the obvious pain, horror, or joy being expressed.

However, the more I have studied the history of art, the better I understand the motivations of the world’s artists and patrons of art, the materials and techniques used to express their beliefs and emotions, and the styles they have evolved to make this expression powerful and unique. Being able to read color, line, and composition, and to decipher the subject matter of a painting, print, photograph, or sculpture helps me to more firmly grasp the message that the artist intended to convey. This opens up a connection to the spirit of that artist—perhaps only for a moment, but this is all it takes. This moment takes me out of myself and provides a glimpse of something larger, higher, and more perfect.

Image courtesy the author

And sharing this glimpse of the state of perfection is what an art historian can do for others. By studying who, what, when, where, how, and why art was created, and sharing this knowledge with others through lectures, classes, exhibition tours, books, and articles, I am able to open a window to the spirits of artists from distant times and cultures and share their insights, beliefs, emotions, and brilliance with people today. I serve as a bridge connecting the spirits of curious people here and now with those of creative people from another place and time.

By introducing audiences to great works of art—or music, dance, theater, or literature—we historians of art and culture provide valuable reminders of the highest levels of human creative endeavor and give us hope that we can all attain a state of perfection and peace.