This translated article was originally published in Buddhistdoor en Español.

This article evolved from the numerous casual chats that arose naturally between the two authors in the framework of classes on the Alexander Technique (AT). One of them as a student of this discipline and a Buddhist practitioner, and the other as a teacher of this technique for more than 15 years. Their exchanges revealed abundant commonalities between Buddhism and a psychophysical re-education method that started in Australia at the turn of the 20th century.We don’t plan on describing every last feature that these disciplines share, but we would like to go over a few of them and reflect on how AT can not only contribute to meditation practice, but also have beneficial effects in our daily lives.

More than 100 years ago, a young Australian theater actor, Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869–1955), made a series of discoveries about how to use his body structure more efficiently, by deep self-observation. These findings established the foundations for a psychophysical re-education technique that, since its beginnings, would be recommended by such celebrated figures as Aldous Huxley, Bertrand Russell, George Bernard Shaw, John Dewey, Nikolaas Timbergen, and Raymond Dart. Today, AT is well known among actors, dancers, musicians, and singers, as its practice is part of professional training at numerous top schools.

From alexandertechnique.co.uk

Specializing in performing Shakespeare, Alexander started to have problems with his voice when acting on stage, to the point where he would be practically unable to speak by the end of shows. Despite consulting numerous doctors and therapists, he did not obtain any positive results, yet felt an urgent need to find answers to the difficulties threatening his incipient yet promising career as an actor. He embarked on a thorough investigation of himself, with desire, curiosity, and a need to understand how his voice worked and why he had lost it. Throughout his quest, Alexander understood from his empirical experience, from his Western mind, that we are indivisible selves, and that using our voices and breathing are not separate from the rest of the psychophysical unity. An apparently isolated ailment could not be overcome without a total change to the entire self.

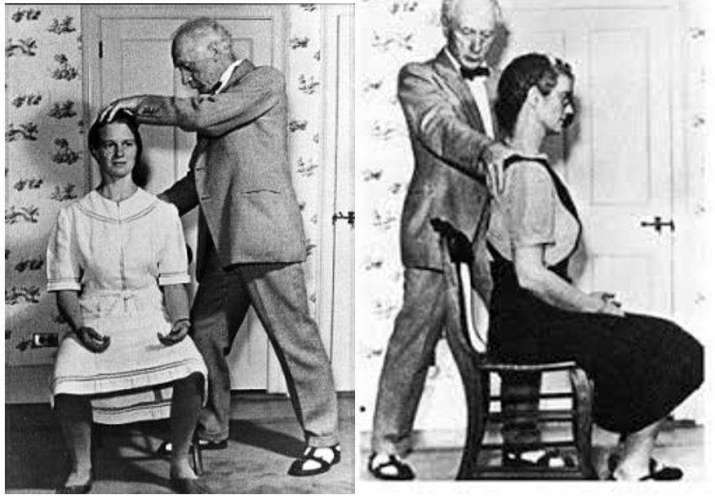

After years of self-observation, aided by the use of mirrors, the way in which he did simple actions like speaking, sitting and standing up, Alexander discovered that the physical structure of human beings is a system that involves a subtle and dynamic balance between all factors of the entire self, a balance that is often damaged, becomes numb, or even collapses. This leads to interference with important functions, such as locomotion, respiration, blood circulation, and digestion. Further, the way we organize the body’s structure at rest or in movement could be inefficient, so that a simple action such as sitting could end up requiring great effort due to excess tension or a lack of tone.

By watching how he moved in mirrors, Alexander not only became aware of how inefficiently he used his own body, but also that he couldn’t trust his own feelings when correcting this use because when he thought he was doing one thing, he was actually doing something else. As he could not trust his sensory appreciation due to it being conditioned by his habits, Alexander had not only to restore and retrain movement patterns, but also his sensory perception through observation.

Alexander also realized that he could not re-establish the use of his body by direct correction, as his attempts to change by “doing something” only created more tension and threw his body structure more out of balance. Alexander thus discovered that, above all, that he needed to observe and recognize where he was interfering. He did not have to directly correct his structure, but instead to stop his habitual reaction to a stimulus. To refer to this process, Alexander developed the principle of “inhibition,” which means not permitting the automatic and habitual reaction to a stimulus. In this conscious stopping is where Alexander believed the freedom rested to be able to decide: to either react like always or choose to not react, or simply do something else. By halting this habitual reaction, a space and time is created in which to look at ourselves. Not doing is, above all, a mental attitude. A decision to stop and recognize the habitual patterns of the use of the self.

By stopping and releasing, it is possible to think of directions. These “directions” are not doing something directly, such as correcting your posture; it entails more of an indirect process that involves projecting messages from the brain to certain parts of the body. These directions involve conceiving of, verbalizing, and even visualizing the body becoming looser, taller, and wider. They are mental instructions that, indirectly, create expansion and suitable muscle tone, letting us recover the length, width, and volume of our body structure and, consequently, re-establish its support mechanism and dynamic balance. If we watch small childrem moving, we can recognize this natural balance and coordination. Not only do they use the whole body, but the entire self is integrated and present in the activity being explored. When the maximum expression of this structure is used, the body’s full potential, balance, harmony, and beauty are all unveiled.

From momtastic.com

For the Western world at the beginning of the 20th century, Alexander’s discoveries represented an innovative look at corporal experience, totally in tune with the Eastern cosmovision and philosophy now known in a good part of the world. A large part of AT practice is based on being present “here and now,” with an attentive, alert, and conscious mind when doing the simplest daily activities, such as sweeping, cooking, or washing dishes. Thus, the effect of AT has been described as “body enlightenment,” experienced and lived in a satiating and visible way by those who practice it, a bodily expansion and lightness that borders on the miraculous.

The points where the cosmovision and practicing Buddhism converge are many. To give an example, deeply observing oneself without reacting or intervening is the basis of Zen Buddhist meditation and vipassana. In the latter tradition, you thoroughly observe all body sensations, either part by part or via a unifying sweep, without changing what you see, which means not reacting automatically to pleasant feelings with attachment, or unpleasant ones with aversion. When you are meditating and feel tension in your shoulder, you observe it impartially without moving or trying to change it. You are practicing what Alexander called “inhibition.”

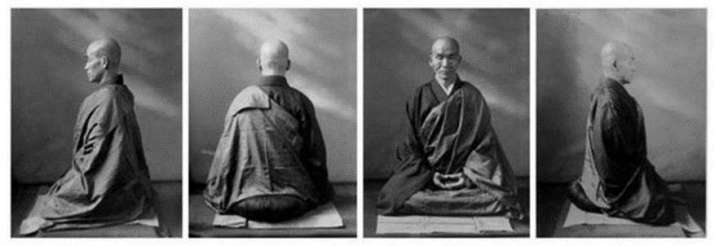

In Zen, you also observe the body, breath, and thoughts, letting mental formations pass by without intervening in your breathing and remaining aware of your body structure. The way you sit in Zen meditation is extremely important, especially keeping the head in the correct position, whether you are meditating in lotus or half-lotus posture. To do so, a series of instructions are given, such as “push the ground with your knees and the sky with your head;” “stretch your neck and tuck your chin;” “nose in a vertical line with your bellybutton.” There is also the idea of illusory sensory perception, and it is well known that we frequently think we are sitting in a correct posture when really we are not. Perhaps one shoulder is higher than the other, or the head is leaning forward, or the spine is tilted to one side. To reverse these postural mistakes, the teacher may have mirrors at the front and sides of the room so that you we correct our posture, while an experienced practitioner may cross the meditation hall correcting the postures of others doing zazen.

More generally, we can state that “not doing” represents not only the foundation of Zen, but also of Taoism and the perennial wisdom of all mystic traditions. You don’t need to rush about seeking the light, as freedom and enlightenment come from stopping and not interfering. Like a glass of dirty water that decants over time, leaving crystal-clear water on top and the mud at the bottom, satori, enlightenment, or awakening will naturally flower when the mind calms down and we stop seeking the fulfilment of desires, including enlightenment. As Zen states, in the same way that adequate breathing springs from an integrated, balanced, and expanded posture, the appropriate state of mind flows naturally from placing deep attention on our physical bodies and our breathing.

With regard to Vajrayana Buddhism, this tradition has stressed for hundreds of years that the body, as it is perceived by non-initiates, is an illusory construction rooted in profound habits of perception. According to instructions from Tibetan masters and lamas, the body is visualized according to a model that questions the Western materialistic conception, so that it appears as luminous, immaterial, expanded, and ethereal. By visualizing the body in this way, we are not replacing a realistic body image with another born from illusion, but instead combating the habit of viewing our own bodies in a karmic or conditioned manner, with a type of perception closer to the truth. Thus, in visualization exercises we build a sacred identity, with the aim of breaking away from the habitual pattern of perceiving ourselves as ordinary beings. The body is progressively transfigured and we experience a utopian body. From this point, we can rebuild the subtle body energy channels with our imaginations to carry out an energy adjustment that balances the physical body.

In summary, one of the most important similarities between Buddhist philosophy and AT is the vision of the nonduality of human beings. Body and mind are viewed as tightly interwoven aspects of a total phenomenon, “like the two sides of a sheet of paper,” as Zen Master Taisen Deshimaru said. Pioneering in his day, Alexander stated that every person is an indivisible psychophysical unity. Thus, our thoughts, emotions, and experiences condition the way in which the body moves, feels, speaks and walks. To this end, he came up with a method that employs thought, image, and verbalization to influence the physical body and improve the general way we react to different situations in life.

Those starting out in Buddhism often do not expect to find that a large part of their practice involves confronting their own bodily and sensory dimension. Thus, during Zen meditation retreats or vipassana, we often hear beginners manifesting their surprise that the practice is “much more physical” than they expected. Even advanced meditators try to follow the instruction to “sit up straight” by “doing” it directly, alternating between stiffness from taxing their muscles when trying to maintain the right posture, or being too lax, which causes the posture to collapse. In this respect, AT can help meditation practice, making it easier for us to remain seated comfortably for longer periods of time by making it possible to find a good support and natural balance.

However, the benefits AT can provide a Buddhist practitioner are not limited to the hours spent sitting in meditation. Often after returning from a retreat, it is hard to maintain the state of presence, alertness, and impartiality in daily life. AT can help us to integrate this mental state in all of our activities, as it promotes attention to the body, emotions, thoughts, and the outside world. Indeed, since the beginning of the last century, AT has helped countless actors, musicians, singers, and people in general to move more fluidly, to have greater mental balance and a relaxed and attentive presence. This makes it likely that the community of meditators could gain a lot from learning this technique. And those who have done so do not hesitate in confirming that AT in itself is a spiritual practice.

Catón Eduardo Carini has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from the National University of La Plata (UNLP), a master’s in social anthropology from the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) and a PhD in anthropology from the UNLP. He works as an assistant researcher at the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) in Argentina and as a lecturer in Cultural and Social Anthropology at the UNLP. Carini became interested in Buddhism in 1999 when he started practicing Zen meditation with French master Stéphane Thibaut at the Zen Association of Latin America. He later dedicated himself to practicing vipassana meditation at centers linked to the Burmese master S. N. Goenka, as well as the practice of the Dzogchen tradition in Vajrayana under the guidance of Tibetan master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu.

Verónica Bellón trained as a dancer and choreographer at Armar Danza Teatro in Buenos Aires. She trained in the Alexander Technique at ATON, the Alexander Technique Opleiding Nederland (Amsterdam, Holland) from 2001–05, under the direction of Arie Jan Hoorweg. She is a member of Asociación Argentina de Técnica Alexander (AATA) and Society of Teachers of the Alexander Technique (STAT). She is a regular teacher at Escuela de Técnica Alexander Buenos Aires (ETABA). Along with her extensive career as a teacher of the Alexander Technique in individual classes, Bellón has also worked in group workshops focused on applying the principles of AT to the performing arts (workshops for dancers, actors and musicians) and yoga practice (training courses for yoga teachers). Verónica is also a teacher of the Shaw Method (AT applied to swimming), training in this discipline in 2009 in London under Steven Shaw, and the Art of Running (AT applied to running), training in 2016 under Malcolm Balk. She has worked with Steven Shaw at several teacher training seminars on the Shaw Method (United Kingdom, Madrid, and Barcelona) and regularly teaches the method at courses at ETABA and in workshops open to the general public.

See more