Orgyen Thukchok Dorje’s vocation as a lay teacher is representative of the Nyingma teaching model: transmitting the Dharma while moving in lay circles such as families and workplaces. Orgyen was born in 1979 in the village of Ngongha, in the southwest of what is today the Tibet Autonomous Region. He fled Tibet in 1985 and studied at the Tibetan Children’s Village school in Dharamsala, India. He earned an MA in English literature from Loyola College, Chennai, in 2004. Orgyen worked with Tibetan human rights groups from 2004–10, and published a book of poems Song Offerings (2009). As a Fulbright Scholar, he obtained an MA in journalism from Emerson College, Boston, in 2012. He also contributed to His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s biography. He is the translator of six volumes of Tibetan Resistance (Guerilla Army) Chronicles into English, which resulted in the publication of The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong: The Untold Story of My Struggle for Tibet (2015) by Gyalo Thondup and Anne F. Thurston. He met his spiritual root guru, Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche, in 2012, and commenced a three-year Dzogchen retreat in 2015. This marked the beginning of his spiritual career. In this interview, Orgyen looks back on what led him to embrace his family tradition of the Nyingma transmission.

BDG: How and when did you decide to become a lay practitioner? What inspired you to take the path? Was it a spontaneous decision or did you plan to become a full-time tantric practitioner?

Orgyen Thukchok Dorje: Karma, or the law of cause and effect, plays an important role on the Buddhist spiritual path. Where we are born and grow up also have a pivotal part to play. Most Tibetans of my generation and those who came before us went through a very difficult period. I witnessed a part of that quite closely.

There was so much human suffering and upheaval when I was growing up in Tibet. It impacted me a lot. So I had a deep conviction that I must find way out of suffering in general. And my escape from Tibet at the age of six and growing up as an orphan further opened my eyes to the suffering and pain of human existence.

In Vajrayana, we accept that the pain and difficulty one undergoes are a direct result of the actions and karmas of one’s past lives. We do not think that we suffer from injustice committed by someone against us, or that someone has wronged us. We place the blame on our own karma and not on others. That really changes the dynamic of how one deals with suffering and how one attains freedom from it. This is the greatest gift and wisdom I learned from my elders. The misery and suffering I undergo in this life are a direct result of my negative karma from past lives. I alone am responsible. This way of thinking is the great blessing of being born into a Tibetan Buddhist family.

I consider the suffering I experienced quite early in my life as a privilege. It is the most favorable situation one has to truly appreciate the teaching of the Buddha. It is because of suffering and misery that I became a Buddhist, not by birth in a Buddhist environment. Suffering is the only way to find freedom from it.

Hearing and reading about Tibet’s spiritual traditions and the life story of the Buddha—how he gave up a royal life after seeing human suffering, and went into the forest and emerged as the Awakened One after six years—all of that really had a deep impact on me.

The life story of Tibet’s famed yogis Milarepa and Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal inspired me. Years went by as I read about the lives of other Buddhist figures. The more I reflected upon the nature of life and suffering, the more my aspirations toward renunciation grew.

Within the Buddhist tradition, there are a range of approaches and methods that are tailor-made to appeal to the diverse dispositions of individual seekers. I was drawn into the Vajrayana tradition because, to me, this path directly reveals the truth in its barest form.

BDG: You have a master’s degree and are a published poet. You have worked with the Tibetan government-in-exile. You could easily have opted for a normal career, but you chose to give it all up to follow the Buddhist path. Why?

OTD: After my graduation, I joined and served the Tibetan diaspora and government-in-exile. After six years of activism, I was convinced that a political solution alone is not the ultimate solution to human suffering. I was convinced that most of them were pursuing careers and privileges. I found myself an odd man out. I soon realised that my life had other purposes.

I pursued a master’s degree at Emerson College because I really wanted to see a different perspective on life and the world around us. I soon found out that the degree was only preparing me for a career in a cut-throat world. Not only that, I also met many rich and successful people who have everything under the Sun, yet they were hopelessly depressed and deeply miserable. Suffering is universal. That realization was the last straw for me. I chose to become a student of the Dharma from that day onward.

BDG: How many years have you been practicing now? Please tell us about some of the gurus you have chosen to follow. Who are they and what they have taught you?

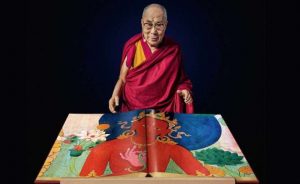

OTD: I have been a student of Dharma for more than 12 years, and always try to be a diligent seeker. I have received many Mahayana teachings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and numerous tantric empowerments and instructions from other masters. In Vajrayana, we never discuss our root guru, so I will not mention him here.

Some 2,600 years ago, Siddhartha Gautama found the answer to human suffering and how to attain liberation after a great spiritual search. He discovered that the way we think of existence is an illusion. He discovered that all phenomena appear before us because of many interlinking, interdependent causes and conditions. The way things appear to our perceptions is far different from how they are in reality. We tend to only see only a tiny, superficial aspect of those phenomena. We then posit that everything we see is real, unchanging, and has a self.

This propels us to cling to the five senses and the temporary pleasures brought to said senses. However, the truth is so much more profound. When one of the interlinking causes and conditions cease to exist, everything falls apart like a house of cards. They cease to exist. This brings to us a great deal of dissatisfaction and disappointment. A mind mired in confusion creates further confusion. We experience acute pain, hollowness overwhelms us, and we can’t let go of our craving, obsessions, and hangups. We are stuck.

We fall into depressive states, and in order to escape, we try to find pleasure somewhere—temporary escapism, fantasies, and obsessions of some kind and form. Again, we will be let down. We are caught in a vicious circle. This is called samsara.

When we die, our consciousness falls into the same trap, and again we are propelled by our mental cravings, born again to suffer and undergo the same vicious circle of suffering. There is no freedom from this bondage. Only spiritual training guarantees us lasting peace and freedom.

The Buddha discovered the great wisdom of shunyata, meaning that all phenomena lack self and true inherent existence. Conventionally they appear to exist before us, but in reality, they are empty of true existence or nature. Seeing this truth grants ultimate freedom to a seeker of truth. The whole of Buddhist spiritual training is about understanding this truth and realizing this paradox. This is the core teaching of all eight lineages of Tibetan Buddhism, and that of Mahayana and Theravada as well.

BDG: What are some of the biggest challenges of pursuing the path of a lay practitioner? Do you ever regret choosing this way?

OTD: Our biggest challenges are not external. They lie within our own untamed minds and in the negative karmic traits that have conditioned our habits. Emotions are highly deceptive and the ego is a great seducer. They are the worst obstacles on the path. Other than that, both monastic life and lay practice have challenges and merits. In the case of lay practitioners, one must find support for one’s livelihood. So, in that sense, it’s not simple or easygoing. Life is stressful. But there are benefits as well, such as how real-life circumstances can make one a better practitioner. Sometimes, living within the secure confines of the monastery can make a person complacent and less responsive to applying spirituality to everyday life.

BDG: Your practice also involves quite a bit of traveling. Where do you spend your time normally and which pilgrimage places do you visit often?

OTD: We visit inspiring places blessed by past masters. We call it pilgrimage, but in reality we camp down for months on end and practice in quiet isolation. I often go to locations in Ladakh, Sikkim, and Nepal.

BDG: What is your main practice now? Do you practice daily, and for how many hours? What are some of your daily practices?

OTD: The spiritual endeavor is a never-ending journey. The goal is to merge or integrate the truth of reality with our very being. Throughout a single day of a Dharma practitioner, from the moment of waking to going to bed, we are concerned only with getting closer to the truth: to understand the nature of emptiness and to apply it to daily life. This is our sole preoccupation as Buddhists. Everything else is secondary, like the rituals, cultures, and methods we employ.

Usually, practice is divided into four sessions in a day. The length of practice depends on the person. Typically, each session lasts about three hours. I don’t follow a fixed pattern, but at least practice three sessions a day. The Dharma practitioner reflects on the four seals of Buddhism:

• The unsatisfactory nature of all emotions we harbor

• Everything we cherish being impermanent, subject to decay and disappointment

• All phenomena, including both the subject (the person) and the object of pleasure, as self-less and having no ultimate basis

• And finally, inner peace and liberation as the result of seeing and realizing the above three truths

In order to keep ourselves sane and grounded on the spiritual path, we also reflect deeply on four thoughts to turn away from worldly pursuits and distractions. They are:

• The infallibility of the law of karma, where we guard ourselves from committing negative deeds

• The defects and demerits of engaging in worldly activities

• The unavoidable truth of death and impermanence so we can prioritize and put things in the right perspective—not to pursue illusions and vain goals

• The rarity and preciousness of human birth that is ideally suited to Dharma practice, thereby motivating us to focus our efforts toward spiritual training day and night

We meditate on loving-kindness and integrate it into our lives. We practice deity yoga, seeing and transforming the ordinary mundane world into the pure perception of non-duality of subject (the ego) and the object. In this way, we are able to leave behind attachment toward the physical world.

In the Ati Yoga or Great Perfection tradition, a teaching brought to Tibet by great Indian master Padmasambhava, there is a unique way of seeing the truth by directly cutting through the duality of the subject (ego) and the object (attachment), and resting in pure awareness. As a result, one comes to rest in one’s Buddha-nature. There is no teaching higher than this. This is the ultimate yana.

BDG: What is the difference between becoming a monk and following your tantric yogi path?

OTD: If a monk belongs to the Theravada tradition, then his goal is to attain individual peace or nirvana. However, in the Mahayana tradition, the goal of a monk is to attain complete enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.

In this regard, there is no difference between a Mahayana monk and a tantric yogi, as far as the end goal is concerned. However, the method or approach to enlightenment is different. In the case of monk who follows the Vinaya, they cultivate good conduct and avoid bad conduct, adhere to ethical discipline, and practice celibacy as the pillars of practice. However, in tantra, there is no attitude to good and bad. That makes it unique and difficult to practice. So it’s not for everyone.

BDG: You were born in Tibet. Did you inherit a lineage, say, from your parents? Were they also serious practitioners?

OTD: I was born into a family of lay tantric practitioners of the Nyingma tradition. I don’t know much about what my father practiced. And it was forbidden to practice openly in those days in Tibet. But I know my father was a deeply spiritual man. He would never part from his rosary.

BDG: I am sure you have also gained some followers after all these years in practice. What blessings do they seek and what sort of advice do you offer them?

OTD: In the Buddhist tradition, a teacher or kalyana-mitra is not an ordinary person. He or she must possess many qualities that are mentioned in the Buddhist scriptures. It is a very important responsibility. In fact, it can be an obstacle if one has not tamed one’s mind and attained realization. Otherwise, it would be like the blind leading the blind. I do not possess any of these qualities of being a teacher. Hence, this question is not relevant to me at the moment.

We do have peers and we share our insights and practices and learn from each other. I prefer to spend the rest of my life in an isolated place applying the instructions of my guru to remove two obscurations that still bind me to samsara. I prefer to fulfil the role of a good disciple.

BDG: The path you have followed is definitely not for everyone. But if there were people who would like to follow this path, what suggestions might you have for them?

OTD: For those who are curious about Dharma practice but are beginners, it is critical to read books written by authentic Tibetan and Western teachers. Go to Dharma talks. It is equally important to contemplate and internalise Dharma literature and teachings as much as one can. One must also introspect. Then one must also meditate and integrate the teachings into one’s daily life.

This leads to the next question, who to follow? And which teacher? This is very important. In old Tibet, disciples traveled to receive teachings from masters. To receive teachings was rare in those days. So those disciples already did their research and homework on their teacher. But things are so different today. In today’s social media world, teachers and masters are so accessible. There are so many promotions and publicity blitzes around, it is difficult to differentiate the authentic teacher from the charlatan. There are many so-called teachers who just pop up without any lineage or proper transmission. There are therefore many hidden dangers and traps. It is monumentally important to find teachers with authentic lineages, or it would be a complete waste of time and energy.

Then there are those of us who have an itch to enter into the Vajrayana world, having been inspired after reading the mind-boggling stories of Vajrayana masters of the past. But here, I believe one must truly refrain from entering the Vajrayana path on a whim. One should take it step by step and tread slowly. There are so many pitfalls on this path; it’s not for everyone. Here, the word guru comes in. The relationship between the guru and disciple is the cornerstone of this path. Therefore, the guru must be an authentic one. If they are not, one is playing with fire. Both the guru and the disciple will be ruined. The disciple must be a seasoned Dharma student and also must fulfil certain qualities before they decide to enter the Vajrayana path.

To sum up, the Buddha taught the Dharma to help us all attain freedom from ignorance and suffering. The teachings are not meant for relaxation, to ease stress, as therapy, or as an escape from undesirable things. All these are diversionary antics. These are self-deceptions.

The Dharma is meant to purify the 84,000 mental defilements and negative emotions, which are primarily rooted in the five poisons: ignorance, attachment, anger, pride, and jealousy. These defilements and emotions are temporary, produced by a confused state of mind. Our true nature is pure and stainless. Just like a pond that is covered by a thick green algae, when the algae cover is removed and cleansed, the pond once again shows its crystalline, translucent character.

Seeing the truth—just like a person who wakes up from a nightmarish dream and feels greatly relieved after realizing that it was only a dream, unreal, an illusion—is enough to free a person from pain and suffering. If we realize and see this samsara as without basis or reality, see it just like an illusion, just like a dream, it will free us from grasping and clinging to self and other, the duality of the subject and object. That is the dawn of freedom and enlightenment within us all.

The Buddha, out of great compassion, appeared on this Earth to reveal his discovery, just like our own teachers appear before us to teach this truth. So must we pass this teaching on to the next generation. To enter the path of the Dharma is to remove all selfish desires and replace them with compassion for all beings. This is, to me, the best way of living our lives.