Buddhistdoor Global contributor and friend Tsering Namgyal has aspired to write a novel for many years. Over the past decade he has absorbed influences from some of the most fascinating, international, and contradictory places in the world—India, Hong Kong, the United States—and brought them into the singular experience of a fictional Tibetan character called Dawa Tashi. Tsering brings this unique perspective to a hitherto untold story of Tibetan Buddhism. He has lived a global life centered in Asia (as opposed to the “global” outlook and lifestyle reflexively matched with time spent in New York City or London), variously living and working in Hong Kong in the relative peace and quiet of Lamma Island, at his home in Dehradun in the northern India state of Uttarakhand, and in Kathmandu. The heart of his novel-writing lies not only in telling a new and unique story, which readers already expect, but in revisiting tried-and-trusted themes and reorienting them toward a different global fulcrum: in this case, Asia, and specifically India, Hong Kong, and the centuries-old relationship between Tibet and China.

As a Tibetan born in India, Dawa is a character at the borders of everything, the geographic and physical embodiment of the bardo, the uniting Buddhist theme that ties the book together. Dawa belongs nowhere yet can go everywhere. He rubs shoulders with Hong Kong tycoons, beautiful and strong-willed women, and Chinese soldiers. Our window into Dawa’s world switches between third-person storytelling and exposition through his inner thoughts laid out in his diary (there are other ways through which his world is reflected back to us: media reports, letters, and so on). We are offered glimpses into his personality, predilections, and preoccupations: a man who will not admit his ambition; from the outset he makes the most of being recognized as a spiritual guru, a “regulator of the afterlife” who has members of high society beating a path to the door of his meditation center in Hong Kong’s prestigious Mid-Levels residential neighborhood.

Another central character who embodies the “Tibetan Dream,” is Khenchen Sangpo, a professor of Tibetan studies. His speech to a group of university students in the US drips with false modesty: “It is indeed quite ironic that an old man who was born in pre-occupation Tibet, and was recognized as a monk-guru very early on in life, will now be lecturing the brightest students in one of the most prestigious colleges in the world’s most powerful nation . . . I am just a simple scholar of Buddhist philosophy, no more, no less.” (132) Khenchen’s adventures and predicaments will shape Dawa profoundly. He and Khenchen are connected by a New York woman called Iris, for whom Dawa feels increasing affection over the course of the novel. Just as importantly, through Iris, Khenchen motivates Dawa to carve for himself a distinctly Tibetan place in the world: to earn power, standing, and security through that most modest teaching of impermanence and humility, Buddhism. Dawa recounts: “If I hadn’t met her [Iris], I would not be meeting Khenchen, the repository of Tibet and her grand history. . . . After meeting him I was so inspired that it shook me out of my lethargy and indolence—and I almost became aggressive, if not assertive. I went for a long run that evening, after which I went to get a haircut, and felt—perhaps for the first time in a very long time—so proud of my Tibetan identity and roots, and felt a swell of aggression rising up within me, a force that I could only call it by its real name of nationalism, a byproduct of nostalgia.” (49)

Tsering recounts that he has received a wealth of feedback to his novel. At book signings, he has been praised for producing a heartfelt and original work, but also criticized in Tibetan circles for not being tough enough on Buddhism, which some see as having stunted the literary creativity of modern Tibetan culture. Others feel jarred by the lack of judgement on how casually and happily Dawa takes advantage of the credulity and desperation of powerful people, and the Sino-Tibetan relationship, which Tsering sees as one of eternal, mutual dependency.

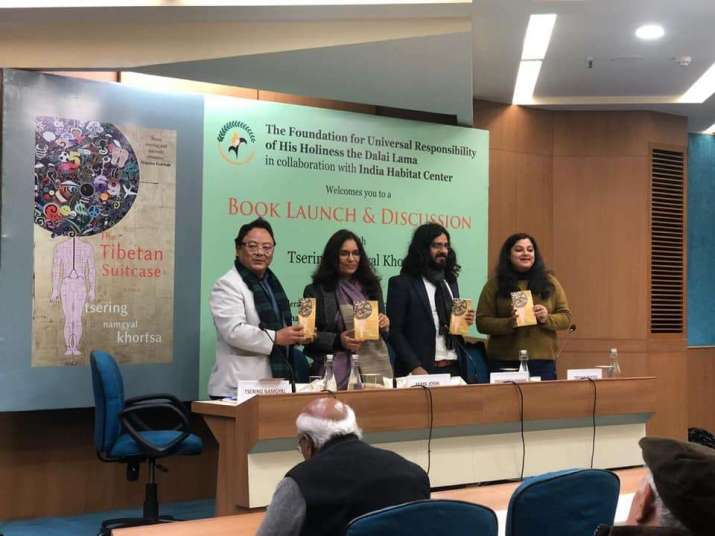

Image courtesy of the author

Iris is also imperfect and, as an American Buddhist, seems to project her own feelings about what a Tibetan “should be” onto Dawa. She writes in one of her angrier letters to Dawa: “It seemed you have nothing new to say, and I am becoming, to be honest, quite bored. . . . Nobody is going to come and say: ‘We are sorry. You are an exiled Tibetan. I am going to serve you a great life in a platter.’ Even if someone did that, you would not find happiness. . . . I also think you should spend your time in Dharamsala, studying Tibetan literature and writing, so that you could at least help translate those great writers into English.” (178) Matters come to a head when Dawa admits to himself: “My story, always rooted in the small hill station of the Indian Himalayas, is too plain and too non-violent, clearly lacking in drama, too peaceful, and conciliatory.” (218) These are not just geographic, political, or cultural borderlands that Tsering explores. They are psychological ones, metaphorical bardo states of mind that flummox us to one extent or another because they are so different to what we may assume about an individual, a society, or a political community.

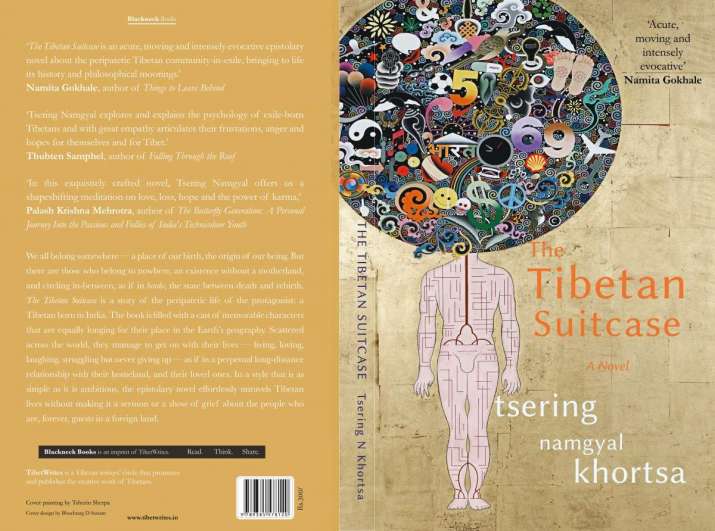

The Tibetan Suitcase is at once dreamy, even romantic, yet visceral and cynical. It is an excellent counter-offer to the Orientalist, borderline-insulting and uncritical adulation of Tibetan culture and the Tibetan mentality that has dominated Anglophone non-fiction and spiritual material, let alone works of fiction and prose, which are especially rare, since so few Tibetan novelists write the kind of English to be published by large publishing houses such as Shambhala (whose books we also regularly review). Tsering’s book is different, and I highly recommend that lovers of Buddhism and Tibet enjoy it. There will be surprises in there for everyone.