This article was originally published in Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that article.

From ganachakra.com

At the beginning of June 1997, New York’s Downing Stadium was preparing to host U2, Radiohead, Sonic Youth, Björk, Blur, Patti Smith, Noel Gallagher, Foo Fighters, the Beastie Boys, Alanis Morissette, and other pop and rock luminaries over the course of a two-day festival. Half an hour before starting, a group of Tibetan monks recited a prayer to bless the concert area. This was the second Tibetan Freedom Concert to raise funds to support the cause of Tibetan independence. Over the following two days, attendees heard exhortations shouted from the blessed stage, such as: “If you want to see democracy in Tibet, make some noise!” and “If there’s anyone here who wants to get with it, get involved and free Tibet, I want you to hit me!” and “The Dalai Lama is a n——r!” As the magazine Rolling Stone pronounced in its chronicle of the concert: “The cultural paradox of the Blues Explosion’s sonic violence coexisting with the monks’ ancient pacifist traditions—not to mention an Über-hipster ironist like [Jon] Spencer preaching social responsibility—proved to be the weekend’s norm.”*

Some pointed out that no matter how well-intentioned, the macro-concert served only to emphasize the huge distance between the cultures of Tibet and the United States. Others would frown at monks who strictly abstain from music and intoxicants, but bless events of this type, replete with both drugs and music—although not alcohol at this festival. However, criticism in this vein disregard an important tradition in the country for which these events were held.

So, although pop-rock did not manage to free Tibet, other popular music has indeed managed to “free” many of its inhabitants. We are speaking of what are known as the Songs of Realization, called dohā on the Indian subcontinent, enthusiastically adopted by Tibetans and even by non-Buddhist groups such as the Sants of Medieval India and the Bauls of today. As Ronald M. Davidson assesses in his book Indian Esoteric Buddhism (Motilal Banarsidass 2003), it would be “difficult to find a similar, Buddhist-inspired language and verse form that has become so very popular and so widely imitated.”

If the cultural setting surrounding the Buddha seriously questioned the value of musical arts, medieval India would embrace and value them again.** From the 12th century onward, Buddhist masters could be found playing instruments, singing songs, and even expressing their experiences of enlightenment in them . . . or so they claimed. Some, like Tilopa, even participated in competitions to showcase their composition skills. Music was not reduced to offerings of “sound” (Skt: śabda) or meritorious rituals accompanied by bells, trumpets, and drums. Instead, music was cultivated and practiced in its most creative and even acerbic aspect.

What had changed in Buddhism during this period of more than 1,000 years? When did the wise Buddhists stop drawing in their “sense faculties” when coming across a musical performance, like the arahant Anuruddha did in a Pali discourse, and begin not only enjoying music but joining the musicians as they played and composed?***

Such transformations are difficult to describe in simple terms, but the Buddhist notion of a śilpinnirmāṇakāya or “craft form body” could have had an influence. They are buddhic manifestations in the forms of craftsmen or works of art, created for the benefit of sentient beings. Examples allude to the mythical master of the artisans, Viśvakarman, or Rabga, an arrogant celestial bard who received a lesson in humility when a buddha showed he could touch all the strings of his instrument by pressing only one, flooding the space with voices of the Dharma.

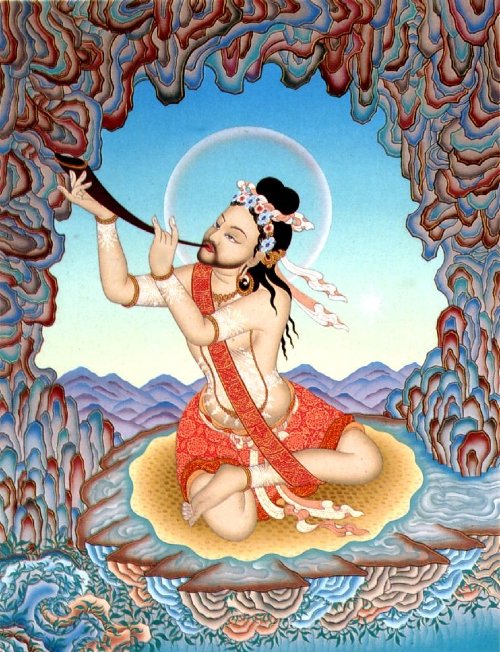

Another possible factor is the growing use of sound as an object of meditation. To this end, Kashmir Shaivism employs string instruments, and Mahayana Buddhist texts such as the Śūraṅgama Sūtra include the existence of meditative states “by means of listening.” The most famous episode in the Indo-Tibetan tradition in this area is that of Vīṇāpa, one of the 84 legendary mahāsiddhas. In his youth, Vīṇāpa was a young Indian prince who spent all his time playing the vīṇā, a string instrument similar to the lute. In his obsession, he barely ate and naturally did not express the least interest in learning the art of regency. His dismayed parents had the yogi Buddhapa summoned to separate him from the music. Since the young man rejected any spiritual practice that did not include his beloved lute, Buddhapa asked him to contemplate the sound of the strings without conceptualizing it: without distinguishing between the sound itself and the mental impression it produced. Nine years later, the story goes, the prince understood the sound that springs from the source of all sounds. He heard the melody from which all melodies arise. This was his song:

With perseverance and devotion

I mastered the vīṇā’s errant chords;

But then practicing the unborn, unstruck sound

I, Vīṇāpa, lost my self****

The cited verses have the style of the Songs of Realization, known in Tibet as mgur or nyamsmgur. The man who introduced them to Tibet was the yogi Marpa, who had learned them in one of his three journeys to India. His disciple Milarepa is remembered as the singing yogi par excellence, to whom legend attributes 100,000 songs. The Kagyü school, with a lineage dated to both masters, has encouraged musical composition among its renunciates and even fully-ordained monks. In music, they found a medium via which they could express their religious emotions in an autobiographical and intimate tone, which is quite rare in traditional Tibetan literature. Like the Bengali Sahajiya, the authors of these songs drew inspiration from the music and lyrics of native folklore, especially from the Amdo area. More elaborate musical formats are similarly attributed to Kagyü ascetics, such as what has been termed “Tibetan opera” (lhamo), presumably invented by a mystical engineer from this school in the 15th century.

bridge-building lama Thang Tong Gyalpo. From tour-beijing.com

While many Tibetans still learn Milarepa’s simple mgur compositions, as well as several others by heart, their form has altered over the course of many generations. The majority have lost the melody and today are recited or, at most, chanted and not sung. Few and exceptional are the masters whose compositions still receive the honor of being performed as songs, even at the cost of melodic and structural changes that make the originals unrecoverable.

Milarepa’s songs enjoy this privilege, although they would not seem to have a specific musical format. One master who did inspire performances with a unique style of their own was Kelden Gyatso (1606–77), whose music continues to be popular in the villages of his homeland, the Rebgong region of Amdo. His compositions, analyzed by Victoria Sujata in her Tibetan Songs of Realization (2004), stand out for two additional reasons. First, they do not come from the fringe, outside of religious institutions, since Kelden Gyatso trained as an academic Gelug monk before he considered becoming a solitary yogi. Secondly, while his lyrics are similar to those of the “crazy” saint Drukpa Kunley and other singing yogis in their subject matter, which includes fantastical tales, talking animals, moral advice, criticism of institutions, and mere amusements, they also make profound expressions of piety possible and allude to tantric secrets and notions of Buddhist metaphysics.

Indeed, Kelden Gyatso’s lyrics reach their highest point when the most esoteric subjects are combined with carefree insouciance, soaring over melodies taken from eastern Tibetan popular music. That is when this erudite Gelugpa and tantric follower, one of the most venerated lamas in the Rebgong region and source of his own lineage of reincarnation, shows that things are never as black and white as one may think at first, particularly in the nondualist world of Tibetan mysticism:

Oh yeah! The result of what has been purified

Hey you! of ordinary birth, death and bardo is the three kāyas [bodies of a Buddha]. Hey!

Hey! Meditate on the Generation and Completion Stages [of deity yoga], which are the purifying agents.

Ha ha! The mind is happy and glorious, get it?

Ya yi ya yi!*****

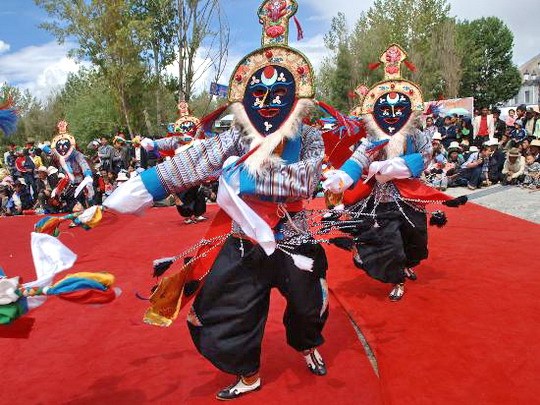

Songs of Realization. From dorjetseringgreentara.blogspot.com

Bridging an abyss of subtlety, Kelden Gyatso’s verses compete in their iconoclasm with the shouts that were heard throughout those two days in New York in 1997: “The Dalai Lama is a n——r!” As befitting his status as a Gelug monk and Kagyü sympathizer, Kelden Gyatso was a practitioner of Mahāmudrā, an initiatory tradition shared by both schools. And one may wonder if there is any better way of transmitting the essence of Mahāmudrā, described by Janice D. Willis as the “naturalness of the innate mind, freed of all self-originated superimpositions onto the real, wherein distinctions of subject and object are completely dissolved,” than leaping over some of the most-ornamented ritual and iconographic systems that humanity has known in pursuit of the simplicity of a peasant song.******

Perhaps it is no coincidence that one of the men who introduced Mahāmudrā in Tibet was the same man who introduced the Songs of Realization: Marpa, Milarepa’s teacher. It is as if he were guided by one of the future verses of Kelden Gyatso: “If you sing a song like this, come to the mountains.”

* Monk Rock: U2, Beastie Boys, More at Tibetan Freedom Concert (Rolling Stone)

** Liberation through Hearing? Perceptions of Music and Dance in Pāli Buddhism (Academia)

*** Anuruddha, The Book of the Eights, 8.46 (Sutta Central)

**** Dowman, Keith. 1986. Masters of Mahāmudrā. New York: State University of New York Press.

***** Sujata, Victoria. 2004. Tibetan Songs of Realization: Echoes from a Seventeenth-Century Scholar and Siddha in Amdo. Leiden: Brill.

****** Willis, Janice. 1995. Enlightened Beings: Life Stories from the Ganden Oral Tradition. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.