The Thousand-Buddha motif is a recurrent theme in the Buddhist art of Central Asia and China. The motif depicts a multitude of buddhas arranged in a grid fashion, all seated in meditation on a lotus pedestal, and its popularity increased predominantly during the Northern Wei dynasty (386-534) in northern China. It was carved on stone steles commissioned by groups of commoners, as well as in the imperially sponsored caves of the Yungang Grottoes in Shanxi Province.

The significance of the Thousand-Buddha motif is varied. Some suggest that the pictorial representation originated from texts on the names of buddhas, and was meant to complement related chanting and meditation practices. Indeed, Cave 254 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, dating to the Northern Wei period (386), features 1,235 Buddha images in its wall paintings. With alternating color schemes, each buddha is accompanied by a small cartouche inscribed with a buddha name listed in the Guoqu zhuangyan jie qianfo ming jing (過去莊嚴劫千佛名經, “Sutra on the Names of the Thousand Buddhas of the Past Majestic Kalpa”). Others emphasize that the motif illustrates Buddhist cosmology in which our world, where Shakyamuni Buddha appeared, is only one of innumerable Buddha-lands across space and time. For instance, in the Mogao Grottoes’ Cave 12, sponsored by a Buddhist monk from Dunhuang in the late Tang dynasty (827–59), there are illustrations of 10 sutras on the chamber walls. When the viewer looks upward, one finds that the entire ceiling, in the shape of a truncated pyramid, is covered with Thousand-Buddha patterns, creating an awe-inspiring experience.

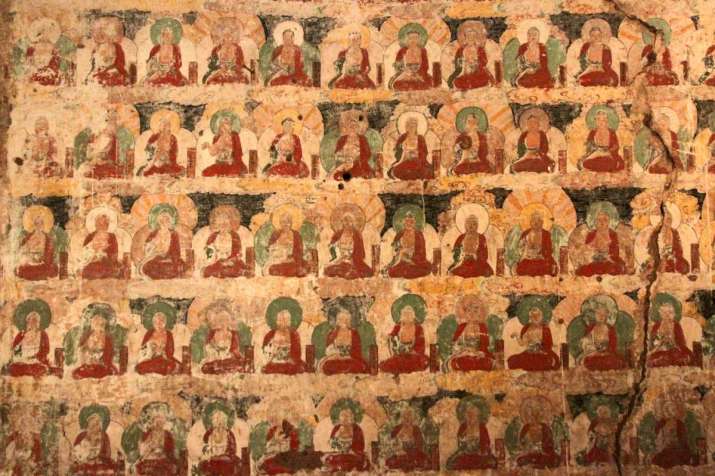

Ultimately, the Thousand-Buddha motif manifests a key teaching of Mahayana Buddhism, that is: all sentient beings equally have buddha-nature and can attain enlightenment. In the arts, devotees express such faith by replacing the names of the buddhas with their own. This can be found on a stele excavated near Xuanzhong Monastery in Shanxi Province, a patriarch monastery of the Pure Land school. According to the inscription, the stele was erected in the third year of the Heqing year of the Northern Qi dynasty (564) by a group of villagers wishing that their fathers, mothers, and relatives of seven generations, and all sentient beings on Earth would attain buddhahood. Another vivid example is the wall painting at Mingxiu Monastery in the same province. Made about a thousand years later, the Thousand-Buddha pattern adopts the traditional techniques and aesthetics from Dunhuang. While most cartouches adjacent to the buddha images are inscribed with donors’ names, some remain unfilled.

Throughout history, the Thousand-Buddha motif has manifested the faith as well as the interests of everybody; nobility and commoners, men and women, laity and monastics. At Dunhuang, to ensure the buddha images were of the same size, artists used pouncing when creating the wall paintings. Despite the different materials, craftsmanship, and scales, the Thousand-Buddha motif has a democratic, non-discriminatory, and even rebellious spirit. In fact, the emergence of the Buddhist teachings, particularly the Mahayana movement, presented a challenge to the elite Brahmin social caste in ancient India.

Similarly, in the 1950s, pop art emerged, rejecting the supremacy of fine art. In the Marilyn Diptych (1962), Andy Warhol made 50 images of American actress Marilyn Monroe, all based on a publicity photo from the film Niagara. Half are painted in bold colors, while half are black and white, supposedly to symbolize the fading life of the celebrity. However, Warhol also embraced tradition. Diptychs had long been a common format in Christian art; and contrary to popular notions, the silkscreen printing technique was not a new invention, but has a root in Song dynasty China (960–1279).

Moreover, the repetition of images has always been a powerful tool in expressing ideas and human emotions. In the Marilyn Diptych, repetition deifies a sex symbol in mass culture. In the works of Yayoi Kusama, a contemporary of Warhol, the repetition of polka dots and other imagery speaks to the anxiety and distress of the female artist that cannot be expressed in words. The audience may have different life experiences, but such sentiments are shared by many in modern times. Therefore, the visual discomfort becomes a means for catharsis. In the case of the Thousand-Buddha motif, repetition promotes a sense of equality, connects each of us with the divine, and creates infinite hope for a higher and more profound state of being.

Looking back, our understanding of the Thousand-Buddha motif may also cast some light on the hundreds of hand stencils at Cueva de las Manos in Argentina. Between 9,000 and 13,000 years ago, the local inhabitants created these images with their own hands by blowing pigments through bone pipes onto the rock. It has been determined that these hand silhouettes of men and women, adults and children, were added through generations. The living conditions of that time were much more hazardous and dangerous, but through these hand paintings, we can sense the strength and unity of this ancient hunter-gatherer community.

History repeats itself, as does art. The development of art motifs is complex and eclectic, but they all originate from the same human conditions and needs; anxieties about life and death, the desire for connection, and a yearning for liberation and immortality.

Special projects from BDG

Buddhism in the People’s Republic

[…] Posted: Thu, 04 Mar 2021 08:00:00 GMT [source] […]