The artifacts that we now categorize as “Buddhist art” were not always treated as art in their original context. Despite superb craftsmanship and profound aesthetics, they were created for the purposes of worship, ritual, and merit accumulation. Just as many key Buddhist terms suffer from misinterpretation in the West, so does Buddhist imagery. In fact, at one point the misuse of the icon of the Buddha became so rampant that the Buddhist community in Bangkok felt the need to put up signs across the city to educate tourists that “Buddha Is Not For Decoration.”

At various points in history, however, ignorance has at times helped to facilitate the circulation of Buddhist images. In fact, this process exemplifies how different cultural systems have interacted. For instance, when the fashion of Chinoiserie swept Europe in the 18th century, pagoda imagery introduced from China developed into a popular decorative motif in a wide range of European arts, including book illustrations, ceramics, textiles, wallpapers, oil paintings, and garden culture. What is more interesting is that this secularization of pagoda imagery also influenced Chinese material culture in return.

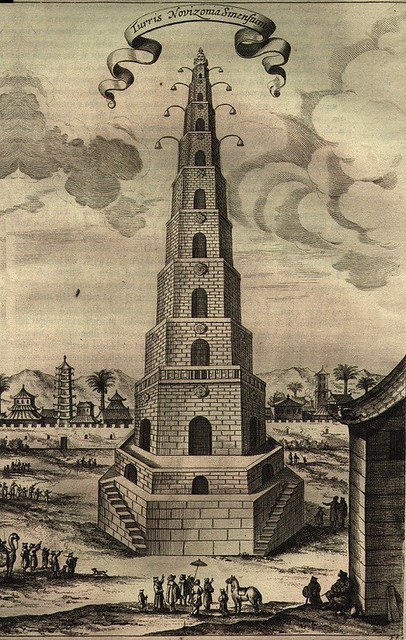

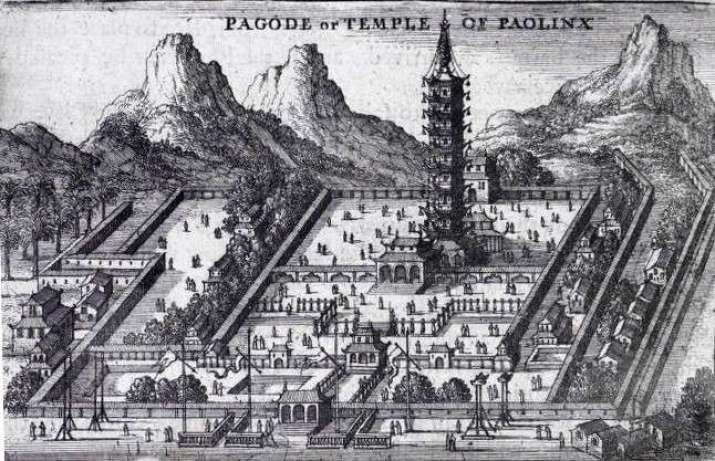

The architectural structure of the pagoda, or ta (塔) in Chinese, originated from the Indian stupa. When Buddhism spread to China, its forms and styles were further shaped by the architectural traditions there. Traditionally, a pagoda is a place of worship in a monastery as it houses relics of the Buddha or of eminent monks, as well as images of deities. European travelogues and treatises from the 17th–19th centuries often include descriptions or illustrations of the exotic appearance of pagodas with multiple stories, polygonal or round in shape, and projecting roofs. Since these works, such as China Illustrata (1667) by Athanasius Kircher, and Geographical, Historical, Chronological, Political, and Physical Description of the Empire of China and Chinese Tartary (1735) by Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, were mainly compiled by Jesuit authors they also emphasized the idolatrous and superstitious nature of such architecture, reflecting a common attitude toward Buddhism in Europe at the time.

Dabao’ensi ta (大報恩寺塔), better known as the Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing, was undoubtedly the most admired example of Chinese architecture in Europe, although the construction material was glazed stoneware rather than the porcelain suggested by its name. It was illustrated in one of the most authoritative works on China of that time, An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces (1665) by Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof. It also found its way into Diderot’s Encyclopédie as an entry. Subsequently, European royals, captivated by the pagoda in Nanjing, commissioned porcelain models from kilns in China. Several of them have survived and can be viewed in the art collection of the British royal family, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. These models bear no Buddhist decoration. Many of them are preserved in pairs, and this is possibly how they were displayed.

Meanwhile, architectural copies of pagodas mushroomed across European royal gardens. Among them, the pagoda in Kew Gardens, designed by William Chambers, has become a landmark of London since its completion in 1762. While the Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing was created to commemorate the deceased family members of the Yongle Emperor (1360–1424) of the Ming dynasty, the Kew pagoda was commissioned by King George III for his living mother as a folly. Chambers introduced this surprising novelty in order to diversify the garden scenery. However, while his pagoda comprises 10 stories, only an odd number of stories are deemed appropriate for pagodas in China. Additionally, the roof ornaments featuring 80 dragons, which have been under restoration since 2015, were definitely Chambers’ invention.

Nevertheless, accuracy was seldom a concern in the vogue for Chinoiserie, and Chambers successfully established himself as an expert on Chinese architecture and garden design. For instance, one of his unusual designs—where a pagoda is combined with a bridge or with rocks—was soon propagated in the pattern books of the day and executed in reality. A Chinese bridge and pagoda in St. James’s Park, now destroyed, were erected in commemoration of the 1814 peace treaty with France. In China, pagodas were attributed new significance as well. Inspired by feng shui principles, an architecture type called Wenfeng ta (文峰塔) came into being. In appearance, it looks very much like a Buddhist pagoda, but its function was to bring good fortune to local scholars and to increase their chances of success in the imperial civil examinations. Nevertheless, it was in Europe that pagoda imagery was transformed into a purely secular decoration.

While existing scholarship has recognised mutual influences in the artistic and cultural exchanges between Asia and the West in the 18th century, Chinoiserie is generally interpreted as a phenomenon in which Western society employed Chinese objects, motifs, and imagery to shape, correct, or re-define itself, with little impact on China. However, my preliminary research suggests that pagoda imagery, devoid of religious significance, was reintroduced to the Qing court as a secular motif. In addition to regular diplomatic and commercial activities between China and Europe, Jesuit artists serving the Qing emperors must have played an indispensable role in secularizing pagoda imagery in its homeland.

As observed by Fang (2004) and Bartholomew (2006), before the Qing dynasty, the pagoda was not used as a decorative motif in China. It was also rarely depicted in landscape paintings. However, after comparing a wide range of artifacts made for the Qing court, it seems to me that pagoda imagery was suddenly included in paintings and ceramics under the Qianlong’s reign (1735–96). Moreover, while European royals were collecting Chinese porcelains, the Qianlong Emperor was fascinated by Western clocks. In his collection, there are several clocks in the form of pagodas, which were made in London, Canton, and the imperial workshop in Beijing. It is more likely that the European models stimulated domestic copies.

Qianlong period, Beijing Imperial workshop. Pagani, 2001

In the original plan for the imperial Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan,圓明園), there was an island reserved for religious buildings, but no pagoda was erected. Curiously, however, in the European Mansions (xiyanglou, 西洋樓), added in 1747 under Qianlong’s patronage, court Jesuits designed a pair of towering fountains (pictured below) that much resembled the nine-tiered pagoda depicted by Kircher. It would only make sense that these architects had studied works by fellow Jesuits, such as Kircher, before coming to China. Moreover, it is possible that they brought some Chinese images, misinterpreted or not, back to China.

by Pirazzoli-tʼSerstevens M., 1987

Unfortunately, we are not able to include all the visual materials that have been surveyed for this research, but it seems evident that pagoda imagery increasingly appeared in Chinese art of the 18th century. In fact, by the Qing dynasty, the religious importance of the pagoda had declined in China, because Buddhist sculptures placed in halls had surpassed relics as the focus of veneration in Buddhist monasteries. This could have been another factor that led to the secularization of pagoda imagery in China. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to see how pagoda imagery enriched material culture in both Europe and China in a rather harmless way.

References

Bartholomew, T. T. 2006. Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art =: Zhongguo ji xiang tu an. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Chambers, W. 1757. Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils. Engraved by the Best Hands, from the Originals Drawn in China.

———, 1773. A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening. London: W. Griffin.

Fang, J. P., 2004. Symbols and rebuses in Chinese art: figures, bugs, beasts, and flowers. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Kircher, Athanasius. 1667. Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis quà sacris quà profanis, nec non variis naturae & artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, auspiciis Leopoldi Primi roman. imper. Antwerpiae: Apud Jacobum à Meurs.

Nieuhof, J., Le Carpentier, J., and van Meurs, J. 1665. L’ambassade de la Compagnie orientale des Provinces Unies vers l’empereur de la Chine ou Grand Cam de Tartarie faite par les Srs Pierre de Goyer & Jacob de Keyser: illustrée d’une très-exacte description des villes, bourgs, villages, ports de mers & autres lieux plus considérables de la Chine. A Leyde: pour Jacob de Meurs.

Pagani, C. 2001. Eastern Magnificence & European Ingenuity: Clocks of Late Imperial China. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Pirazzoli-tʼSerstevens M., 1987. Le Yuanmingyuan: jeux d’eaux et palais européens du XVIIIe siècle à la cour de Chine. Paris: Editions Recherche sur les civilisations.

Buddhistdoor Special Project 2018

[…] https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/the-secularization-of-pagoda-imagery-in-18th-century-europe-an… […]