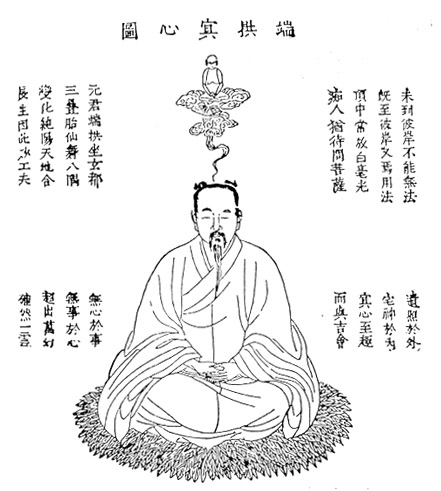

The Secret of the Golden Flower is a late Tang dynasty (618–907) meditation manual for laypeople attributed to the legendary scholar, poet, and mystic Lu Dongbin (796–1016), well known as one of the eight Taoist Immortals, who lived to be 220 years old. Ancestor Lu is the patron of acrobats, martial artists, magicians, and barbers (another way of saying traveling opera performers), and also of the Daoist energetic meditation practices known collectively as Inner Alchemy. Many famous legends concern Lu Dongbin, including one where, after an encounter with Buddhist Chan master Huanglong Huiji, he abandoned Inner Alchemy for the direct practices of Chan, the Chinese precursor to Japanese Zen.

So, Lu Dongbin is also considered a patron of Chan. Not only is Ancestor Lu actual-legendary but so also are the ancient practices for experiencing primal consciousness. They go by many names: the Golden Flower, the Golden Elixir, the Golden Pill, Touching the One, among others. The Golden Flower has parallels in the mystical practices of many religious traditions, East and West. Its whole argument is that reality can be apprehended directly, without cultural embellishment. The Japanese Heian-era poetess Ono no Komachi, wretched and 100 years old, sitting on a tombstone and winning an argument with sophistic Zen monks who mocked her, stated it this way: “The soul is a mirror that hangs in a void.”

This mixed image, of the patron of Inner Alchemy turning to the Buddhist Chan practice of essence, perfectly corresponds to the transcendent nature of The Secret of the Golden Flower. It treats the direct experience of one’s own primal reality as the basis of Taoist and Buddhist practices. A lay cult around the practice of the Golden Flower emerged in the Tang dynasty, avoiding culturally specific terms and arcane metaphoric language. The Secret of the Golden Flower is that rare Chinese spiritual classic for which the reader is not required to know much about Chinese culture, Confucian ethics, Taoist mysticism, or Chan riddles. The purpose of the exercise is not to inculcate sectarian exclusivity or adherence, but with the utmost essentialism, to empower a normal individual with the skill to experience the source of their own existence, and to come to learn the subtleties of that experience; and of getting to that experience. The Secret of the Golden Flower is about making that experience of connection to primal reality a genuine way of conducting everyday life.

The manuscript of The Secret of the Golden Flower and its appearance in the West follows a pattern of emergence taken by other seminal texts of Asian spirituality, most clearly in the translations of German Sinologist Richard Wilhelm’s (1873–1930) I Ching, and by W. Y. Evans-Wentz’ (1878–1965) translation The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Wilhelm’s German translations of the I Ching, 1923, and The Secret of the Golden Flower, 1931, both translated into English by Cary F. Baynes, were cultural milestones in the West. Like Evans-Wentz’ Book of the Dead, these books were wildly popular, found in beatnik and hipster homes. In the United States during the 1960s, you could buy them at drug stores. Later scholars railed against the veracity of the original text sources and the credibility of the translators, but none of that has impacted the importance of these translated texts as markers of cultural integration.

For good or bad, each of these three books mentioned had commentaries by psychologist Carl Jung, whose ideas were also the rage in the early 20th century. Contemporary Buddhist scholars sometimes still substitute the Jungian “archetype” for the Buddhist “deity,” as if that is an uncomplicated improvement. In fact, where Jung appears in the earliest Western translations of practical spiritual texts, it is an indication of the Western mind struggling to understand something that it doesn’t understand. This new psychology seemed so scientific, rational, and suited to Western minds. Jung believed Westerners were not able to use Asian spiritual techniques because they were so psychologically different. These are all eminent men who advanced the School of Wisdom in the West by quantum infusions. Wilhelm and Jung knew little about Buddhism and Zen, however. Information and experience was scarce.

Pioneering modern translator Thomas Cleary also points out the problems with Wilhelm’s Golden Flower, both with the authenticity of the source document, as well as with basic Chinese grammar and the descriptions of processes. He concludes that Wilhelm’s watershed translation is unreliable, but he does it with understanding and respect. Above all, he credits Wilhelm with selecting the text in the first place from among the superabundance of Chinese spiritual texts unknown to the West. Who knows when this amazing spiritual masterpiece would otherwise have emerged in the world? Cleary writes that he would not have translated it anew save for the fact that it already existed and was known. He appreciates the need to adapt a foreign spiritual teaching to another culture, but insists that process cannot include insufficient knowledge of Chinese and, more importantly, cannot misrepresent the processes described as something altogether different. Cleary took particular issue with Wilhelm’s term “circulating the light,” when it should read “turning the light around.”

Chinese culture, and its practitioners of everything from ritual to meditation, opera, and martial arts, embraced the spiritual truths and practices of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism (born as it was in Hinduism), and uses their best and most useful parts without concern for exclusivity or having to make a choice of one path over the other. The famous image of the Three Vinegar Tasters, in which Lao Tzu, Confucius, and the Buddha are each tasting vinegar and describing it slightly differently, simply expresses this unity. The point is that they are united in tasting the same bitter thing. This image of the three masters tasting the source was so well known that it took on many forms, like a meme does in today’s visual culture. The masters came to be depicted, for example, as three beauties standing around a jar of vinegar. The universality was obvious. Everyday spirituality. Spiritual awareness and practice was among the people.

here depicted as three beauties. Woodblock print, Komatsuken

Shoshoken, 1766. Image courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Secret of the Golden Flower is an actual meditation practice, well over 1,000 years old and used by lay people for centuries. This is important to an understanding of ancient Asian movement practices such as yoga, tai chi, Buddhist cham, Newar carya nritya, and virtually every other ancient sacred dance. Most ancient sacred dances are meditative in one way or another, whether a Sufic trance or the mental artistry of Japanese Noh. One main distinction between Eastern and Western dancing is that Eastern traditions, particularly sacred ones, have a fully developed inner technique that corresponds to external body movement. Western dances don’t.

The Golden Flower not only transcends religions and cultures, but movement disciplines from martial arts to Chinese opera to Zen meditation and painting. It is about living and acting with emptiness. This mystical skill is considered essential, primal, individual, and autonomous. It has been and is widely applied to different fighting, dancing, and meditating techniques. As such, it is a rare practical pivot of Mind from the ancient world. The Golden Flower is a mind-body practice that has lasted centuries and been used in countless ways. Today, we can use the same manual as lay practitioners of the Tang dynasty and Shaolin warrior monks.

the late Great Grand Master of the Shaolin Temple Shi SuXi. Golden Flower is a fundamental practice at the Shaolin Temple

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Secret of the Golden Flower, Part Two

Buddhism and the Martial Arts: A Conversation with Scott Park Phillips

Immortality and Invincibility, Part One: The 108 Luohan System

Power and Beauty: Robert Wilson Takes On the Last Dynasty

When Guanyin Jumps Off a Cliff