Prayer is an ancient rite and a practice whose origin cannot be traced. It is not the invention of a single prophet or religious tradition. It’s safe to say that it has been part of human culture since time immemorial and then further back, predating any written history. When our common ancestors inhabited the African continent, before they began to explore the uncharted regions of this giant planet, surely they developed a more shamanic spirituality, worshipping nature’s spirits to overcome dangers, which might be wild beasts, the wrath of the elements, or illness, the source of which was utterly mysterious. In such a society, prayer must have begun as an act of worshipping deities who were supposed to have much more power than humans to control the natural world. Offerings and prayers were done to please the deities so that they would reverse harms and bring good luck to the individual or her family or tribe. Without needing to go back with a time-machine or conduct needless anthropological research, we can see the function of prayer in early human society by simply observing such rites practiced by the many indigenous communities around the world today.

One of the most significant developments that humans underwent was the transition from the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers to an agrarian culture, which gave rise to the creation of complex civilizations that brought about new developments, such as cities, religious and political institutions, rigid systems of hierarchy, and genius inventions such as advanced tools, sophisticated architecture, and written language. People also began to record religious teachings and prayers, through which rites of worship became more formalized. This allowed religious institutions to develop their own traditions with unique idiosyncrasies demarcating each one from another.

It can be noted that there is a fundamental difference between prayers in theistic and non-theistic traditions. In many theistic traditions, there is one omnipotent being who is the holder of the power to create the whole universe; he is therefore the mightiest being the human mind can conceive—the king of kings and the most worthy being to be worshiped. Many religious observances in these traditions are mediums through which worshippers can feel that they’re in direct or indirect communication with the almighty divine, allowing them to request salvation for their souls, or even for earthly fortunes to be bestowed upon them.

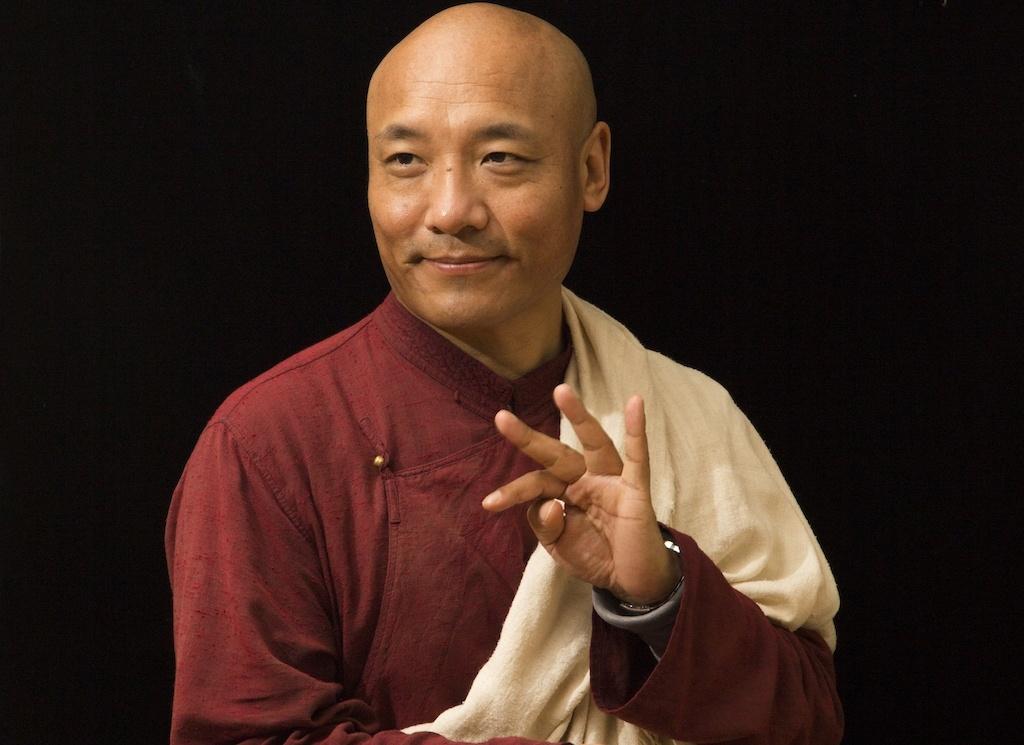

Prayer is an important rite in Buddhism, just as in any other spiritual tradition. Yet the purpose and meaning of Buddhist prayers are quite different from those in Abrahamic traditions. Buddhism is a non-theistic tradition that places great importance on the practice of the Dharma as a way to inner liberation. Buddhist followers often pray to buddhas, bodhisattvas, and spiritual masters. One of the meanings behind these prayers is to invoke the enlightened qualities of our own heart and mind through letting go of the ego’s resistance to humility. For example, by praying to Tara, who is none other than our pure true nature, a profound compassion toward the whole world can be invoked. Tara is a female buddha in tantric Buddhism, loved by Tibetan people. Tantric Buddhism teaches that the very nature of our mind is luminous, pure, and already enlightened—and that is Tara. Similarly, Tibetan Buddhists often pray to Avalokiteshvara, the Buddha of Compassion, as a means to invoke love toward the whole world. In general, our love can be quite self-centered—we might direct our love toward specific people whom we care about, but not the entire world. And it has limitations. Conversely, praying to Avalokiteshvara can help us to transcend all limitations, attachments, and biases, to hold everyone in our heart with true kindness and caring.

Tantric Buddhist practitioners often visualize the sacred forms of lineages masters and chant poetic prayers to them with devotional melodies. In my lineage, we pray to lineage masters, such as Guru Rinpoche or Padmasambhava, Yeshe Tsogyal, and other revered masters of the past, or to our own Dharma masters. Then, the act of praying becomes a powerful method that inspires us to drop into a realm of mind that is already free. Such a liberated state of mind is our innate buddha-mind, which is called “the true guru” in Dzogchen language. There are many inspiring stories about people who have experienced inner awakening by praying to the lineage masters.

Many people also naturally tend to pray when situations in their lives become tough, or when beloved ones and friends are in turmoil, or when feeling hopeless. Prayer can be a source of courage and insight when we need them most. Some people might find that prayer is passive and not regard it as active engagement with life’s situations. The truth is that prayer can be active and can be a right way to engage with situations with which we are struggling. If our heart is numb and oblivious to the difficulties of the world, we will be hibernating in a cave of self-centeredness and will not feel the impulse to pray for the well-being of others. This is why being oblivious to the world is form of ignorance, which is one of the three inner poisons, along with greed and hatred.

Right now, the world is facing whole set of new challenges that seem to be beyond our capacity to deal with—climate change, pandemic, war, political division. These developments can make us feel that the world is descending into chaos. Such a feeling is not only unhelpful but also naïve. The human world has been going through immense difficulties from its very beginnings, and will never be a perfect heaven that fulfills our wild, utopian ideals. Instead, we must believe that we can overcome our challenges and find meaning in our best efforts to deal with them. As such, now is not the time to sit back, but a time to act. Our right action begins with prayer. This is that time to pray for the world to find peace, to find healing, to find harmony, and to find equality; not with moral indignation but with a compassion that sees and accepts the imperfect nature of all things that exist.

See more

Related features from BDG

The Creative Flavor of Vajra Songs

The Practice of Nonviolence

Buddhist Predictions for the Future

Buddhist Economics: Toward a Happier Society