In October 2023, the members of the eco-temple network in Japan welcomed fellow member Emilie Parry from the United States and a group of 12 international journalists from the Jefferson Fellowship Program of the East-West Center of the University of Hawaii. The tour was divided into two main sections with visits to the Kanto and Kansai areas of Japan. The Kanto portion visited the eco-temples of Rev. Hidehito Okochi. The Japan eco-temple group also led the journalists on a four-day reality tour of Fukushima to see the lingering effects of the nuclear disaster there. This is the fourth time the group has led such an international tour of Fukushima since 2012.

Background

The broad purpose of the Jefferson Fellowships is to enhance public understanding through the news media of cultures, issues, and trends in the US and Asia Pacific, with a special focus on a particular theme. The 2023 Jefferson Fellowships explored a theme of “Inequality in the US and Asia.” An immersive dialogue, travel, and reporting program to Honolulu, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Fukushima, and Kyoto contextualized and compared widening disparities of income, wealth, and opportunity within the US and Asia. The program enabled journalists to better understand the distributional consequences of technological change, globalization, and market reforms in dominant globalized industrial systems, and emergent models and theories for markets and governance of the 21st century and the Anthropocene. From the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the impact of artificial intelligence (AI), to New Systems Markets, Climate Smart Markets, and the Great Turning or Sustainable Revolution, this program critically engaged with the liminal and applied spaces where theory and policy meet lived experience, agency, and opportunity.

The theme also explored how income and wealth inequalities are reinforced by inequitable access to opportunity in such critical areas as food systems, education, healthcare, financing and credit, housing, and infrastructure, and the new models responding to, or further aggravating, disparity. In particular, Japan has long been considered one of the world’s most equitable developed countries due to income and inheritance tax policies that hinder the accumulation of capital over generations, as well as social security benefits that significantly raise the net incomes of the country’s low-income citizens. Inequality, however, is on the rise, driven by: a greying of society; intergenerational, gender, and urban-rural wealth disparities; and the growth of irregular employment over life-long employment.

The culture of silence and denial in Fukushima and Japan

Local concern has been high since the beginning of the Fukushima disaster in 2011 for the young people of Fukushima. They are exponentially more susceptible, the younger they are, to cancer, especially thyroid cancer, from the radiation that permeates the air, water, and soil of the region. Rev. Okochi, his colleagues in the Interfaith Forum for the Review of National Nuclear Policy, and other Buddhist organizations, such as the NGO AYUS, were active in the early years of the disaster to provide safe places for young people to escape their local radiated environments.

By 2022, these concerns had led to despair, with some 300 cases of thyroid gland cancer being diagnosed in young people in Fukushima Prefecture. This figure can be extrapolated to an average of more than 30 people per 100,000, which is much higher than the development rate of thyroid cancer of 1.7 people per 100,000 among late teens in neighboring Miyagi Prefecture. (Oiwa) Today, these residents face the double barrier of the government’s denial of the linkages between such cancers and the fallout from the nuclear disaster, as well as the pervasive culture of silencing their voices to maintain the “harmony” and peace of the community. Rev. Okochi and the Interfaith Forum continue their campaign to have these voices heard.

Ajisai no kai: The Supporting Group for Patients of Thyroid Cancer

The Supporting Group for Patients of Thyroid Cancer is a group of young people with thyroid cancer, their families, and supporters based in Koriyama City, Fukushima. Although experts and media consider pediatric thyroid cancer as a mild form of cancer that does not require treatment, this is not always the case. This group supports each other by sharing information in order for the patients to receive better treatment and live a better life as much as possible. This group does the following projects throughout the year:

Café gatherings: about every other month, they organize occasions to know each other better, to exchange information, to learn about thyroid cancer, to participate in cooking and pressed-flower classes, and so on.

Outreach program: they perform home-visits of patients, providing supplies and counseling on the issues faced by the families. For the patients whose illness is severe, they support them to receive second medical opinions as well accompany them to the hospital/clinic in order for their treatment to be improved.

Research and advocacy: They collect updated information for the treatment and improvement of quality of life from academic societies and seminars regarding the thyroid. They also try to enhance the rights of patients through exchanging views and opinions with National Diet members and local diet members.

The empty promise of how technological progress will solve our human condition

If there is a visual symbol for the nuclear disaster of Fukushima that parallels the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima, it would be the giant billboard over top the main shopping district of the town of Futaba, just a few kilometers from the Fukushima No.1 reactors. The sign reads “Nuclear Power: Energy for a Bright Future”—a monument to Japan’s “recovery” or “reconstruction” from World War II but now to the brokeness of that recovery in a “disconnected society” rife with mental illness, suicide, and environmental disasters.

Sumio Konno is from the nearby Tsushima District, also a highly radioactive area. He was a longtime employee of the nuclear power plants in the region, working as a skilled technician, as opposed to the disposable labor force who undertook the hazardous cleanup work. At the time of the disaster, he was working in the Onnagawa nuclear plant with three reactors. Although this plant was located at the very heart of the tsunami, it did not endure a significant accident such as the one at the Fukushima No.1 reactor, where safety conditions were severely neglected. By the time Konno could return home, his wife and young children had already evacuated. They now reside in a temporary house in Fukushima City. His house remains in Tsushima, but it does not seem that he and his family will ever have a chance to return. Tsushima District is still designated as a difficult-to-return area, and only 1.6 per cent of the town has been cleared for return. This 1.6 per cent was assigned as a Specified Reconstruction and Revitalization Base Area, and decontamination efforts were made by the government. However, the rest of the town has not yet been tackled. Konno’s house will probably eventually be subject to be demolition. He has to choose what to do with this asset.

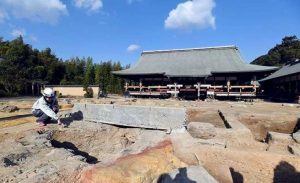

Konno led our group to his parents’ house and the home of his ancestors. To be able to enter this area and lead our group, Konno listed the official purpose to visit his ancestors’ graves—an access once denied. The group had to enter this area and his house wearing protective Tyvek suits. Observing the abandoned remains of the house, ransacked by wild animals, and especially the family Buddhist altar with pictures of generations of family left on the walls, was deeply sobering and one of the most impactful moments of our tour. Needless to say, Konno no longer believes that nuclear energy can bring any promise for our lives and conducts these tours regularly to educate outsiders of the ongoing reality of Fukushima. When the same term “recovery” or “reconstruction” is used to speak of this region, Konno responds: “That’s the last thing I want to hear. These are not words that should be used loosely. Reconstruction is about things returning to normal, and then standing up and starting again. There’s no such thing as reconstruction when you can’t go back to normal and when you can’t rise up again.”

Konno also led us on a tour of the Tanashio Industrial Zone, 10 kilometers north of the stricken reactors. This zone is part of the Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework, which is a national project aimed at restoring the industry lost this area and building a new industrial base in the area. It is filled with mega-solar, hydrogen fuel technology and robot test project sites—what appears to be another attempt at the promise of a “bright future” with the wonders of technology. Perhaps the most bizarre site in the area was the building of a dairy farm between this site and the stricken reactors. The possibility of dairy cows ingesting radiation and transmitting it to humans through their milk is a fairly well established fact. The audacity to try to convince and sell to citizens milk farmed from a region next to the second-largest nuclear accident in human history boggles the mind.

Competing narratives of history

One of the fundamental problems that still exist in Fukushima are the different narratives on how life has unfolded since the disaster. The central government is very focused on following its tradition of massive industrial projects as a barometer of the well-being of the nation and its citizens. On our next stop, we visited the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, which presents a narrative created by the Fukushima prefectural government. There is quite an amount of critical information in the museum, specifically portraying the accident as a man-made one due to the negligence of the Tokyo Electric Power Company and the central government. However, the prefectural government’s message also has a level of denial due to its desperate hope for reviving the region. Thus, a voice of bravery, energy, and optimism (core Japanese cultural values) permeates the museum with constant reference to “recovery” and “reconstruction.” In this way, one of the glaring omissions of this museum is proper information on the ongoing health menace of localized radiation and the rates of cancer of young people in the region.

A third narrative is found in the efforts of Konno and others, such as at Our Disaster Memorial Museum. This is a museum created by photojournalists and community people who wanted to deliver their experiences, messages, and lessons from the earthquake and nuclear disaster. The word moyai is the theme of this museum, which means the strong ties among people. One supposes that real “recovery” and “reconstruction” cannot begin until at least the latter two voices of prefectural government and local citizens are reconciled, and better yet all three voices including outside national interests are reconciled.

Resiliency and the building of an alternative society among Fukushima residents

Our last night in Fukushima was spent at the Futabaya Ryokan (a traditional inn). According to its host, Tomoko Kobayashi, they had to evacuate after the earthquake in 2011. The tsunami reached the front door of the inn. However, a year after the earthquake, when people were allowed to enter the area only during the daytime due to the radiation, she started to prepare to reopen the inn. It took two years for restoration. Kobayashi is also interested in restoration of the community, and the inn serves as a hub for people concerned with the issue coming in and out of the area. During our time there, we learned of a citizens project to publish a book detailing the true extent of radiation from nuclear power plants around the country. Performing incomplete surveys of the extent of radiation, especially in Fukushima, is one of the many ways that the government avoids responsibility for this issue and tries to perpetuate the “myth of safety” around nuclear power. Various citizens groups are working hard to present a different picture of the reality.

Nihonmatsu Eino Solar is a farm-based power generation company operated by three organizations: Gochikan, which creates local energy sources in Nihonmatsu City in cooperation with various sectors aiming for self-supporting community, local cooperatives: Co-op Miyagi and Co-op Fukushima; and the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies, a non-profit think-tank to provide basic support. Sunshine Company is a corporation qualified to own cropland established to develop this project. Hiring two staff, one of them a returnee from the nuclear accident, it operates six hectares of farmland with a view of Mt. Adatara. They produce renewable energy equivalent to the usage of 618 households (3 per cent of all households in Nihonmatsu City) or 1,855 battery-powered vehicles, as well as plenty of agricultural produce, such as Shine Muscat grapes. With the realization of a new type of agriculture and land use in the decarbonized era where agricultural production and energy production have a synergistic effect, they seek to develop the next stage of Fukushima.

The Society of Organic Farming in Nihonmatsu (Yu-No-Ken) was the original organization of Nihonmatsu Eino Solar/Sunshine Company. In 1978, Yu-No-Ken was established and started to produce organic agricultural products and direct sales to customers. In 2001, it was certified by Organic JAS (Japanese Agricultural Standards), which was established in 2000. In 2006, the Act for the Promotion of Organic Agriculture was enacted, and in those days, Yu-No-Ken’s customer base grew.

In 2011, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident occurred. Serious radiation fell around Nihonmatsu as well, although it was never designated by the government as an evacuation zone. Agricultural produce was heavily affected at the beginning. Yu-No-Ken began measuring radiation levels of their produce and sold only those under a minimum level, but it also lost most of its customers. They felt at a loss as to whether they should continue farming. Yu-No-Ken joined with an NGO based in Tokyo called Alternative People’s Linkage in Asia (APLA). Together they researched what they could do for Fukushima’s agricultural sector. In 2012, they began a series of seminars focused on the future of Fukushima from a variety of aspects, one of which was energy.

In 2013, Yu-No-Ken began researching renewable energy. At this time, they were rather opposed to solar panels, fearing that they might involve the deforestation of mountains and produce waste later on. But in 2014, they visited Germany, with support from APLA and the Buddhist NGO AYUS (a member of our eco-temple circle in Japan) to learn about renewable energy projects created by community or agricultural organizations. They increased their interest in biogas energy production using food waste, which could create cyclical agriculture. However, the more they learned about biogas energy production, the more they realized its difficulties. In 2015, they had an opportunity to visit other farmers who had started agri-voltaics, which sets solar panels above the farmland and produces energy and agricultural products simultaneously. Yu-No-Ken also thought that this might be the best way for them to try at first, since they already had land and this system was less harmful to the environment. Yu-No-Ken, APLA, and AYUS held a kickoff gathering in Tokyo that year and called for supporters.

By 2016, Yu-No-Ken submitted an application for permission to convert agricultural land into such agri-voltaic land, but it took about 18 months to be accepted. Construction was finished in 2018, and Yu-No-Ken’s agri-voltaics started to produce energy. In 2019, Kei Kondo from Yu-No-Ken established Nihonmatsu Eino Solar and Sunshine Company.

Many thanks go to AYUS and its director Mika Edaki for organizing most of this tour along with Rev. Hidehito Okochi. AYUS is an NGO established by Buddhist priests based on the Buddhist principle of “interbeing.” AYUS raises funds mainly among Buddhist communities to provide NGOs that work on human rights issues, humanitarian aid in disaster areas, and so on—especially for those who are left behind by mainstream aid projects and funding.

As for the people and communities affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, at the beginning, AYUS cooperated with NGOs, beginning their humanitarian assistance in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures. After half a year, AYUS found that Fukushima had received the least funds and assistance among three due to the nuclear power plant accident. As such, AYUS has mainly cooperated with NGOs working in Fukushima as well as organizing retreat camps for children living under the influence of radioactivity.

References

Oiwa, Yuri. “Thyroid cancer diagnosed in 104 young people in Fukushima.” Asahi Shimbun. 24 August 2014.

See more

Jefferson Fellowship Program (East-West Center)

Building a Buddhist Temple Community as a Mechanism for Environmental and Social Change (INEB Eco-Temple)

The Voice of Young Plaintiffs Suffering from Thyroid Cancer in Fukushima ・311子ども甲状腺がん裁判·提訴集会 311

We are firmly opposed to the discharge of radioactive “ALPS treated water” into the Pacific Ocean! (JNEB)

The Unsurpassed Wisdom of Enlightenment and the Right to Life of Cattle (JNEB)

Japan Network of Engaged Buddhists (JNEB)

International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)

Related features from BDG

Rebirth and Revolution – Engaged Buddhism in Japan: A Conversation with Jonathan Watts

Bowing to Ajahn Sulak at 90

The Path of Engaged Buddhism in a Divided World: An Interview with Ven. Pomnyun Sunim

Engaged Buddhism: The Role of Spirituality and Faith in a Divided World

Peace, Planet, Pandemic, and Engaged Buddhism: From a Divided Myanmar to a Divided World

Ven. Pomnyun Sunim: Buddhism in a Divided World

Compassion and Kalyana-mittata: The Engaged Buddhism of Sulak Sivaraksa

Very informative. Thank you for documenting this.