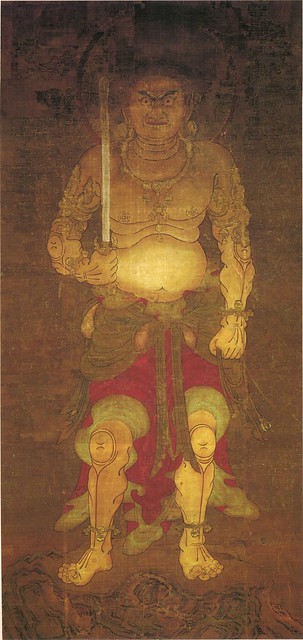

As the wrathful manifestation of Dainichi Nyorai (Skt: Mahavairocana), the primordial center of Esoteric Buddhism, Fudō (Skt: Acalanatha) acts as the immovable and indomitable chief of the Five Great Wisdom Kings (Jap: Godai Myōō). He is often depicted sitting or standing in the center of the five, or as an independent deity. In texts translated by eminent Buddhist scholars during the 8th century, Fudō is described as carrying a treasure sword (Jap: hoken) in his right hand and a lasso (Jap: kenjaku) in his left. The sword cuts through the delusions of the mind, freeing it of the three poisons (confusion, greed, and anger); the lasso snares those who stubbornly resist the gracious invitations of the Buddha and brings them back into the fold. Fudō is also frequently surrounded by a fiery mandorla, representing his purifying flame.

The concept of an implacable and steadfast wrathful deity has its roots in the Hindu deity Shiva; Hinduism believing that all deities are separate personifications of certain aspects of the primordial god. There are three iconographical details that are shared with Acala: the serpent, the lasso, and the flames. A snake is sometimes shown coiling around the phallus of Shiva, also called the linga, much like a dragon sometimes wraps itself around the sword of Acala. Shiva was often depicted with a lasso or snare and Acala is rarely found without one. Finally, both Shiva and Acala burn away delusion with purifying flames, though Acala’s is on a personal level and Shiva’s is more cosmic. No representations of Acalanatha are extant in India; scholars have had to depend solely on scriptural descriptions to draw parallels between the Wisdom King and Shiva.

Acala as a named deity is first mentioned in 709 in a translation of a sutra by the Indian monk Bodhiruci (672–727). Iconographic descriptions identifying him as a Wisdom King were then translated from a section of the Mahavairocana Sutra (Jap: Dainichi-kyō) by Subhakarasimha (637–735) in 724. In 736, Vajrabodhi (671–741) translated into Chinese the Secret Dharani Rites of the Messenger Acalanatha, the first text dedicated solely to Acala. It is in this text that the Indian monk makes absolutely clear that Acalanatha receives his authority as a manifestation of Mahavairocana, intended to preserve “tranquility in the three realms.” Up to this point, Acala was subservient to Trailokyavijaya (Jap: Gozanze).

It was Amoghavajra (705–74)—Vajrabodhi’s disciple—who was responsible for moving Acala to the center of the Five Wisdom Kings in Trailokyavijaya’s stead, due to the monk’s fervent belief that Acala, as a manifestation of the cosmic Buddha himself, was better suited for the chief role. It is in this role that images of Acala traveled to Japan—where he was named Fudō—from China via iconographical drawings carried by, most notably, Kūkai, Enjin, and Enchin. These drawings were then turned into three-dimensional objects of worship, first in the Goei-do at Tō-ji by Kūkai. In contrast to Amoghavajra’s Acala, whose iconography predominantly stemmed from the Diamond World (Jap: Kongōkai) Mandala, Kūkai’s Fudō was based heavily on the iconography of the Womb World (Jap: Taizōkai) Mandala. Each of the great teachers Kūkai, Enjin, and Enchin became associated with a particular iconographic presentation of Fudō; the former two with imported Chinese forms and Enchin most famously with the Yellow Fudō, who appeared to him in a dream, the commissioned painting of which would become the first original Fudō iconography in Japan.

Despite Enchin’s introduction of an original Fudō form, it is still Kūkai who is considered the true propagator of Fudō iconography in Japan. Kevin Bond explains that “Amoghavajra’s writings were so influential they inspired Kūkai to construct the Nin’no gyo mandara, a three-dimensional representation of the deities contained in the Kodo Lecture Hall of Kūkai’s head Shingon temple, To-ji. It is primarily due to his inclusion in the Nin’no gyo mandara that Fudō became well-known in Japan.” The iconographies brought to the archipelago by Kūkai are of two types: the seated Fudō from the Takao mandara and the standing Fudō from a variant of the Nin’no gyo mandara. It was these that led to the formation of the “Kūkai style.” It should be clarified, though, that both these forms were subservient deities and not the central deity Fudō would become in subsequent generations, specifically under Enchin.

Similar to the 32 signs of the enlightened Buddha, Fudō too was designated iconographic features—19 of them. Amoghavajra specifically described signs affiliated with certain parts of Acala’s corporeal form as the focus of Sanskrit prayers; these include the hair, the braid, the eyes, and the weapons. Kūkai then attempted to abbreviate and systematize the conceptualizations of Fudō by Amoghavajra in two of his own translations: the Prescriptions for Invocations of Fudō Myōō and Abbreviated Verse of the Nineteen Visualizations and [the Syllable] Ham. Kūkai’s visualizations were written in five-character verse, so the descriptions were notably sparse and left much to be further described. It was not until the Tendai monk Annen (841–915) that the Nineteen Visualizations took the expanded and canonized form as we know them today in his Womb Realm Prescriptional Rites of Fudō.

Fudō also appeared in a triad form with two child-like disciples (Jap: doji). Known as Kongara and Seitaka, these two acolytes are the best known of eight that have at times accompanied Fudō. Seitaka represents the evil, unruly child brought under the control of the wrathful deity Fudō, whereas Kongara embodies obedience and servitude. Many sculptural representations of Fudō Myōō may have initially included the two doji, but they may have been lost; paintings are much more likely to have preserved the triad due to it being one complete piece as opposed to three separate pieces.

As a wrathful deity, indomitable force, and dominant figure in Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Fudō Myōō has appeared in countless media. His countenance can of course be seen as both sculptures and paintings in Buddhist temples and museum collections, but he is also a popular subject in tattoo art, manga, and anime.

References

Bond, Kevin. 2001. “Ritual and Iconography in the Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Tradition: The Nineteen Visualizations of Fudo Myoo.” Thesis. McMaster University.

Gray, Basil. 1961. “Fudo.” The British Museum Quarterly. Vol. 24, No. 1/2. British Museum, pp 46–50.

Ito, Shiro. 1998. “Stylistic Appraisal of Tendai Lineage Fudo Sculpture.” Bukkyo geijutsu, No. 236.

Linrothe, Rob. 1986/87. “Provincial or Providential: Reassessment of an Esoteric Buddhist “Treasure.”” Monumenta Serica, Vol. 37. Taylor & Francis, pp 197–225.

Moran, Sherwood F. 1961. “The Blue Fudo: A Painting of the Fujiwara Period.” Arts Asiatiques, Vol. 8, No. 4. Ecole francaise d-Extreme-Orient, pp 281–310.

Okada, Barbra Teri and Kanya Tsujimoto. 1979. “The Fudo Myo-o from the Packard Collection: A Study during Restoration.” Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 14. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp 51–66.

Payne, Richard K. 1988. “Firmly Rooted: On Fudō Myōō’s Origins.” Pacific World, new series, No. 4. 6–14. Institute of Buddhist Studies, pp 6-14.

See more