The premise of Buddhism is that the very nature of our mind is already pure, in the sense that it is not gripped by the kleshas, or inner poisons, of desire, greed, and egoism. This is a liberating truth about our ourselves, and we can have a glimpse of it now and then. This is not just an idea or concept, but a living reality to which you and I can bear witness. Therefore, trying to actualize the nature of mind is not only worthwhile but is the most worthwhile endeavor that can be undertaken by a human being. The importance of such an endeavor was recognized by many individuals in the past, who saw that the full understanding of the transcendent nature of the mind leads to an inner liberation that surpasses all worldly joys and material achievements. These individuals are often called the mahasiddhas, arhats, and vidyadharas.

While the true nature of mind is inherently pure, unless we engage in spiritual practice, whatever is veiling this natural state will not disappear on its own. For that very reason, Buddhism developed various levels of spiritual practices that may sometimes seem contradictory from the outside. The reason for the great variety is that different people are on different stages of the spiritual path, having differing capacities, psychological make-ups, and abilities to comprehend. There is not one system that will work for everybody. The plurality of the various systems is often regarded as the genius of the Buddha’s enlightened qualities: vast compassion and skillful means.

Tantric Buddhism, which is widely known as Vajrayana, is a system that is unique among all other practices because it allows us to embrace everything, including our shadow side, our flaws, and our shortcomings, as a medium for our spiritual practice. Its main methods are called sadhanas, which are structured methods that can be practiced either in everyday life or intensively during a secluded retreat. Sadhanas work with different deities. Some very popular sadhanas among Tibetan yogis are focused on Padmasambhava, Tara, Avalokiteshvara, and Vajrayogini. Some of those sadhanas are very concise, while others are lengthy, involving other circles of complementary practices.

Traditionally, the way to choose a sadhana is either by having a strong affiliation with one of the deities or by receiving it from your teacher. For example, the famous 19th-century terton Dudjom Lingpa (1835–1904) composed the sadhana of Khroda Kali in his revelatory writings, and he gave this practice to many of his students. Some of them practiced it as wandering yogis, and taught it to others throughout Tibet. Some of his followers decided to dedicate their practice to this one sadhana throughout their lifetime.

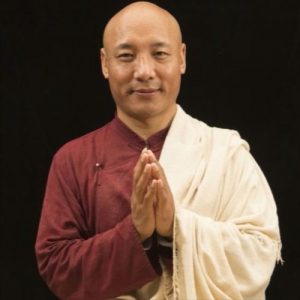

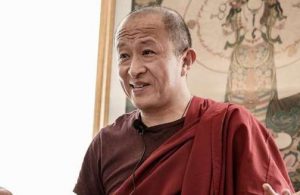

My own guru, Lama Tsurlo, was not one of the famous spiritual celebrities of Tibet but was well-loved in my hometown. I see him in my heart as one of the enlightened beings. You may wonder which practice helped him to become awakened in this lifetime. At a young age, he met a Nyingma master, Trinley Lingpa, who was often known as Apang Terton, and he studied under him for many years. At some point, Lama Tsurlo felt a strong affinity with the sadhana of the wrathful Padmasambhava. He practiced this sadhana while living in seclusion as a hermit. He accumulated millions of mantra recitations of this particular practice, which is an incredible feat in itself. I believe that this practice was the catalyst for his spiritual attainment.

A sizable number of people in the West practice Vajrayana and have even completed the traditional three-year retreat. However, the archetypal symbolism and the rituals of the sadhanas can appear very foreign to the general untrained Western mind. General Buddhist philosophy and straightforward meditation seems to have greater appeal to many people in the West. It is not unusual for people not to be interested in sadhanas, yet be able to connect to the formless Dzogchen practice. Nevertheless, it is helpful to bear in mind that tantric sadhanas have incredible transformative powers if we understand them and develop love toward them.

See more

Related features from BDG

The Role of Prayer

The Creative Flavor of Vajra Songs

Chod: The Practice of Cutting Through