Museum renovations have been a significant part of Singapore’s Jubilee Year celebrations in 2015, with the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) opening a new Ancient Religions gallery in the early part of the year. Its thematic approach presently draws solely on pan-Asian Buddhist art traditions, from India to Southeast Asia to China. However, it will later also incorporate the Hindu deities and images related to nature-spirit worship, partly in response to visitors asking to learn more about the complementarity of these traditions. In time, additional galleries will expand on the theme of ancient religious traditions, and will feature both Islamic and Christian art in Asia.

The current display is arranged around art styles broadly spanning the first millennium of the Common Era. The narrative traces the earliest developments in India and the spread of the Buddhist tradition across Asia. Moving anticlockwise, the story follows a southern journey that connects South Asian traditions with China through Southeast Asia.

terracotta

Several works have a commanding presence, and through clever juxtaposition, speak of distinctive art styles as well as connected traditions. The head of a bodhisattva from Gandhara displays the Greco-Roman features typically associated with this early cosmopolitan culture of what is today northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. The striking facial features and wavy locks were modeled in clay, whilst the lion mask spewing strings of pearls on the headgear and earrings appear to have been made in a mold (see Chong 2013). The urna (tuft of hair) at the center of the forehead is a subtle indentation, unlike the protrusion more often found on stone images of this time. Framed by neo-classical columns at the gallery’s center, the magnitude of the piece comes into focus as visitors enter the long corridor that leads to the gallery.

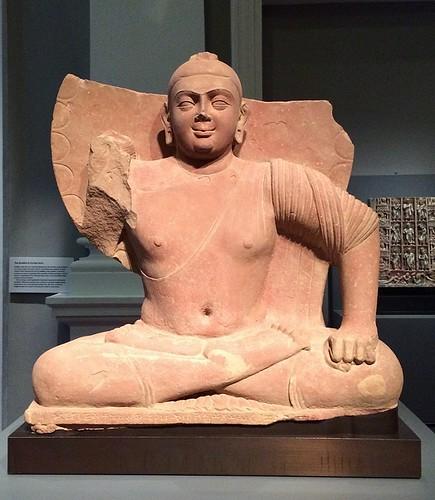

In contrast to the sharply contoured figures typically depicted wearing voluminous robes from Gandhara, the mottled-red sandstone images from Mathura have an abstract appearance. They were intended to convey the concept of the Buddha as the superhuman mahapurusha, or “great man.” An adjacent seated image of the Buddha from Kushan embodies some of the special marks (Skt. lakshana) associated with his powers, including the Wheel of Law (Skt. dharmachakra) on the soles of the feet and a curled topknot (now missing), usually conceived in the form of a snail shell.

sandstone

The finely clinging robes draped over the left shoulder reveal a body that is expanding with prana, or inner energy, while his enlightenment is celebrated on the reverse of the back slab, in the form of a Bodhi tree. As one of the earliest figurative forms of the Buddha, an image such as this was presumably considered a highly meritorious gift. An inscription along the base informs that it was donated by a monk of some authority. It reads: “Installed by the monk (follower of Vinaya) on the 8th day of the first fortnight of hemanta (winter) of the 19th year of the great king Kanishka,” which dates this piece to 96–97 CE.

fiery pillar. India, 3rd century, limestone. On loan from the

Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi

The aniconic representation of the Buddha is also illustrated in the South Asia section of the gallery. A stone fragment from the railing of the Great Stupa at Amaravati depicts the empty throne with a fiery pillar. Capped by the Triple Gem, the pillar reminds us of the key constituents of Buddhism: the Buddha, his teachings, and the community of monastics.

sandstone. Image courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum,

Singapore

The pillar is also an important Vedic symbol of Shiva’s unlimited power—to establish his pre-eminence, Shiva appears in the form of a flaming pillar in between the gods Vishnu and Brahma, who are fighting over their prowess, and challenges them to find the pillar’s ends; they are unable to do so, thereby indicating Shiva’s infinite nature. The other manifestation of Shiva’s power is the linga (literally “sign” or “mark”), as seen in the illustrated piece from the display on Southeast Asia. This phallic form has the face of Shiva carved on one side and is set within a base representing the female principle, or yoni. Indian religions spread through trade into the surrounding region, and particularly to coastal areas such as the Mekong Delta in south Vietnam, which has some of the earliest archaeological evidence of Hindu and Buddhist material.

7th/8th century, stone

A continuity of style between South Asia and China is highlighted by the bejeweled form of the bodhisattva. Earlier forms from Gandhara appear to have been taken up by Tang period (618–907) sculptors in China. The stone fragment of a torso illustrated here may well have been made for a cave temple. It stands with one leg slightly bent as in the Indian tradition and is slightly flatter than the Gandharan figures, but nonetheless is draped entirely in a dhoti and jewelry. The looped, beaded necklace and long chain worn front and back bear lotus pendants, and are typical of the elaborate adornment of images of bodhisattvas rather than Buddhas.

9th century, sheet gold and electrum. Gift

of Joe Grimberg and Rosalind Shellim in

memory of Aaron Brooke David

bronze. Image courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore

These stylistic links are further seen in the relations between China and Southeast Asia in the evolving Mahayana and tantric traditions. Around the 9th century, the cult of Avalokiteshvara became very popular in the central Vietnamese kingdom of Champa and also in the Dali kingdom, in today’s Yunnan Province in China. Two forms of the bodhisattva of compassion are displayed side by side, their stylistic similarities underpinned by the tributary, trade, and other cultural exchanges in which Champa and the Dali kingdom engaged. The standing figure, made in sheet gold and electrum, has been identified as the form of Avalokiteshvara known as Lokeshvara, or Lord of the World. The same type of figure was cast in bronze in Yunnan, where it was known as Acuoyue Guanyin. The bronze seated image here is stylistically very similar, with a slender body and lithe arms. Both figures are draped in a simple dhoti and have a tall hairstyle in which sits the figure of Amitabha.

Valley, excavated in 1941, 5th–9th century, bronze.

Image courtesy of the Asian Civilisations Museum,

Singapore

Clearly, the complex history of the Buddhist tradition and its spread through Asia is a challenge for an exhibition of this size. There are still many gaps in the museum’s collection that curator Theresa McCullough intends to redress. For example, the Gupta period (4th–6th century), a high point in Indian art, remains absent for the time being. However, its importance as a source of inspiration for Southeast Asian artists is addressed. The rare bronze standing Buddha from the Malay Peninsula illustrated here is thought to be one of the earliest from the region. The right hand in the gesture of gift-bestowing (Skt. varada mudra), the other holding the end of the robe, the posture with one knee bent known as tribhanga, and the simple monk’s robe depicted as clinging to the body, are all attributes that can be found in the Gupta style.* Flows of influence did not only travel in one direction. The great maritime trading power known as Srivijaya saw donations flowing back to India and attracted Chinese monks to study Sanskrit at its center in Sumatra at this time (7th–13th century). Monks such as Yijing (635–713) stayed there en route to India in his search for sutras that could be translated into Chinese. These wider ramifications of the flow of ideas and religions will be addressed in several other galleries planned for the museum.

The ACM’s Ancient Religions gallery offers an intriguing introduction to the diverse artistic expressions of Asia during the first millennium. It is a story that appeals to religious practitioners, art history enthusiasts, and the general visitor. Most of all, it is a story that reflects the island nation’s own role as nexus of trade and cultural exchange, and one that is clearly still evolving.

* For a comparison of this piece with the post-Gupta images of Nalanda, see Heidi Tan, “Examining Early Buddhist Materials from Srivijaya,” in On the Nalanda Trail. Buddhism in India, China and Southeast Asia, Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2008, pp. 83–89.

References

Chong, Alan. 2013. “Buddhist Figural Sculpture.” In Devotion and Desire: Cross-Cultural Art in Asia: New Acquisitions of the Asian Civilisations Museum, 17. Singapore.

Heidi Tan was formerly principal curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. She is presently an Alphawood Foundation scholar pursuing a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

All images are by the author unless otherwise stated.