Victoria Montrose (“Tori” to her friends, a fittingly Japanese epithet) has been immersed in Japanese culture since childhood. Victoria was four when her American father married her Japanese stepmother, and she subsequently recalls sharing many conversations with her father, a Buddhist, about faith and belief during her years of adolescent curiosity. Growing up in Los Angeles in the 1990s, she was exposed to a slew of American media interpretations of life in Japan that didn’t quite match her personal experience.

To this day Victoria believes in the need for cultural interpreters: “To bridge the gap I noticed between the media and pop culture and what I privately knew about Japanese culture. We need cultural interpreters to help the West better understand the people and religions of not just Japan, but much of the rest of the world too.”

Victoria chose to study Japanese in high school and, after earning a BA in political science (with a concentration in international relations and a minor in history), taught English in Japan for two years as part of an exchange program. “I thought I was going to go to law school, but through a series of personal revelations I just decided that while I could be very happy practicing law, academia felt like a more intriguing challenge,” she recalls. Back in California, she took an MA in Buddhist Studies at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, and then applied for a PhD program at the University of Southern California.

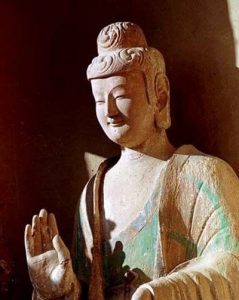

Her paper at the 6th Annual Tung Lin Kok Yuen Canada Foundation Conference, “Buddhism in the Global Eye: Beyond East and West” (which ran from 10–12 August at the University of British Columbia), was written on the basis of what she humorously calls “a weird affinity that I have with the university,” and an urge to explore how the West understands Japanese Buddhism—as a serene, Zen-like movement at ease with modernity and the secular world.

“How do we think of Japanese Buddhism and why? If you fold back a few layers, you’ll see that Buddhist scholars played a role in curating a lot of the images we have about Japanese Buddhism in the West during the Meiji and Taisho periods,” Victoria notes. “I was interested in tracing how this genealogy of understanding came to be. I’m curious about the process of how Japan unveils its self-understanding to the world.”

Victoria highlights how these curators of Japanese culture serve as an example of Asian agency in the modernization of Buddhism (as opposed to the dominant trope of the Western or Christian imposition of “modernity” on a passive Asia): “From the beginning of the Meiji period, we see conscious thought and intentionality in various publications, such as those of Okakura Kakuzo, who wrote about topics like tea and the Japanese spirit directly to a Western audience.” In a general sense, Japan was constructing an ideological edifice that would be fit to contend with the free-for-all, aggressive international competition of the mid-to-late 1800s that was ignited by Western expansionism and economic imperialism. The humiliation of unequal treaties dictated to the Tokugawa Shogunate was still fresh in memory of the Meiji oligarchy.*

The need to respond to European and American military, economic, and ideological challenges reflected Japan’s increasingly pluralized religious landscape and growing debate about the Western understanding of “religion”—the Buddhist priest Shimaji Mokurai’s (1838–1911) incredible contributions to the Japanese reconceptualization of religion is a story for another day. This was all unfolding to the alarm of the Buddhists, who observed with horror the end of Buddhism’s hegemony after the Shogunate’s fall, the dissolution of the parish and temple registration system, and a period of persecution of Buddhists.

Three of Japan’s Buddhist universities—Jodo Shinshu’s Otani University, the Soto Zen school’s Komazawa University, and the multi-sectarian Taisho University—were fast learners of the ways of Tokyo Imperial University (Todai, established in 1877), the first Western-style university in Japan. “Buddhist universities looked to what Todai was doing, with the agenda of training priests and giving them the tools to respond to Western scholars,” Victoria explains. “To do that, Buddhist scholars needed to reframe their methodologies and objectives.” For example, Todai studied Buddhism as literature rather than as a living religion. Buddhists wanted to answer the escalating challenges of foreign critics and nonbelievers, and universities provided good “idea-labs” to test ways to survive in Meiji Japan’s environment of ideologies competing for state legitimization.

The precursor to Otani University, the “proto-university” Gohojo (Institute for the Protection of the Dharma), was founded in 1868 and incubated debate on the direction of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, as well as studying disciplines that presented both challenges and opportunities, such as astronomy and scientific or critical inquiry. However, increasingly hostile conflicts between “progressives” (who favored engagement with non-Buddhist ideas) and “conservatives” (who wanted a return to sectarian basics) reached a tipping point with the assassination of reformer and Gohojo leader Senshoin Kukaku (1804-71). These were clearly not just ivory-tower indulgences. Ideas mattered and the stakes were extremely high for Buddhists, who felt their religion would be rendered extinct unless, just as Meiji Japan had reformed itself into an extraordinary modern state fit to compete with the great imperial powers, Buddhism was reformed into an adaptable force for that could withstand and challenge competing intellectual forces such as Christianity, science, and secularism.

However, Victoria contends that, on the whole, the Otani denomination’s timely response to the intellectual challenges posed by science, Western expansionism, and new configurations of religion and secularism was successful. The Buddhists were able to create new modes of knowledge and transmission that met the standards of science and modernity. She also agrees with scholar Hayashi Makoto of Aichi Gakuin University, who argues that those sectarian universities that generated the most original scholarship during the Meiji period remain the most powerful and prestigious among Japanese Buddhists today.

The consequences for the priesthood itself were far-reaching. The modernization of Buddhist education put Buddhist leaders in a better position to interact with networks of higher education in Japan and around the world. It ushered in their professionalization, since they could no longer take for granted the social status accorded to them before the Meiji era—no longer were they simply leaders of the sangha, they had also formulated new ways to be useful to the state. They were modern educators domestically, and cultural and intellectual ambassadors internationally. Although not necessarily “heroes,” they are certainly historical protagonists that deserve far more attention than they have been hitherto accorded.

* Unequal in the modern diplomatic sense that the terms of the treaties were not reciprocal: the shoguns were not granted the right to establish ports in Washington or London.