For better or worse, Zen (Ch: Chan) Buddhism has frequently been associated with martial arts and sword fighting. Obviously, there is some validity to this association as, for example, the Shaolin Temple of the Chan tradition gave rise to Gongfu, and Rinzai Zen of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) was utilized by members of the samurai class. Also, phrases such as “the oneness of the sword and Zen” (Jpn: kenzen ichinyo) imply a deeper connection between the religious tradition called Zen and a general genre of physical exercises designed as preparation for combat and armed conflict. But often these connections have been used to assign militarism to the Zen Buddhist tradition as a whole, or to romanticize martial arts as a spiritual tradition. In this essay, I want to reflect on life lessons from sword fighting manuals that may be influenced by, but are not representative of, everything associated with the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The movie Hero (Ying xiong; 2002) tells the story of a nameless fictional assassin who wants to eliminate the first Qin emperor (259–210 BCE). In the climactic scene, the character referred to as “Nameless” confronts the emperor and, in their conversation, the story of how he was able to get close to the emperor is told three times, depicted in the movie in three different colors (red, blue, and white). According to Nameless’ first version, he killed three famous assassins to earn a private audience with the emperor. The emperor modifies the story and suggests that Nameless did not kill the assassins, but that they sacrificed themselves for the greater good. Finally, Nameless reveals that actually no one was killed since he knows a technique by means of which the victim only seems to be dead but awakens later.

In the English-language version of the film,* the emperor then identifies three stages of sword fighting: “In the first stage, man and sword become one with each other. Here even a blade of grass can be used as a weapon. In the next stage, the sword resides not in the hand but in the heart. Even without a weapon, the warrior can slay the enemy from a hundred paces. But the ultimate ideal is when the sword disappears altogether. The warrior embraces all around him. The desire to kill no longer exists. Only peace remains” (Hero. Yimou Zhang. 2002).

Anyone familiar with the long history of martial art narratives and manuals should recognize this theme. It goes back all the way to the ancient Chinese text Zhuangzi by the philosopher of the same name (369–286 BCE), who identified three different kinds of sword: the “sword of the common man,” which “slashes through the neck; and below, it scoops out the liver and lungs;” the “sword of the feudal lord,” which “is in harmony with the minds of the people;” and the “sword of the son of heaven,” which “is regulated by the five elements . . . its unsheathing is like that of the Yin and Yang.” (Zhuangzi 2006–19)

Both the movie Hero and the Zhuangzi identify three different “swords:” the physical and external sword that takes the lives of living beings, the mental sword that controls and, potentially, kills living beings by means of thought, and the “sword of no sword,” (Stevens 1994) which paradoxically describes a state in which violence is abolished and harmony prevails. This can be read in two ways: 1) The goal of practice and even armed conflict is, ultimately, peace; and 2) The whole rhetoric of stages in sword fighting is metaphorical and, as in the case of Zhuangzi, serves to illustrate the immorality and absurdity of war.

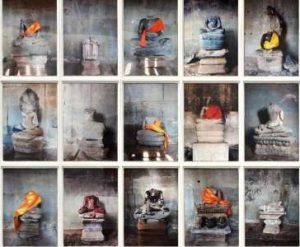

The Japanese popularizer of Zen Buddhism in the anglophone world, Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō (1870–1966) gives these three stages a decidedly Buddhist reading. He illustrates the three stages of sword fighting with three popular images from Japanese Buddhist iconography: Acalavidyārajā (Jpn: Fudō myōō), Mañjuśrī (Jpn: Monju), and Mahāvairocana Buddha (Jpn: Dainichi nyorai). Suzuki explains that “Acala . . . carries a sword and he will destroy all the enemies of the Buddhist virtues,” “the sword of Mañjuśrī is not to kill any sentient beings but our own anger, greed, and folly. It is directed toward ourselves,” and “[t]he Vairocana holds no sword, he is the sword itself, sitting alone with all the worlds within himself.” (Suzuki 1959, 90) Suzuki’s analogy is extremely interesting. While his interpretation of these three canonized depictions is rather idiosyncratic, Suzuki identifies the three stages common to many martial arts and meditation manuals with the three highest of the “five transformation bodies of Buddha” (Jpn: gobutsu no keshin) central to Shingon Buddhist iconography and liturgy.

The final text of my exploration of the three stages of the sword is Takuan Sōhō’s (1573–1645) Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom (Fudō chishin myōroku). While Takuan also implies three stages—in his case, the “ordinary man (sic),” “man (sic) of half-baked wisdom,” and “immovable wisdom” (Takuan 1986, 22–3)—what is of interest here is his description of the third stage as “wisdom” (Skt: prajñā), to be exact, “immovable wisdom” (Jpn: Fudō myōō). To Takuan, this wisdom is, contrary to Suzuki’s claim, embodied by Fudō myōō himself. (Takuan 1986, 21) Fudō’s fearsome exterior is to frighten demons and his sword serves to cut off delusions.

This immovable wisdom is facilitated by the mental state Zen Buddhists refer to as “no-mind” (Jpn: mushin). Takuan offers his readers two illustrations of this no-mind: The Thousand-armed Kannon Bodhisattva (Chi: Guanyin) and water. If Kannon were to be single-minded or one-sided—Takuan’s descriptions of the “deluded mind” (Jpn: moshin)—only one hand would be functional and the other 999 would be useless. Only if Kannon does not focus on any one particular arm, all 1,000 arms are set in play. Similarly, “if the mind congeals in one place and remains with one thing, it is like frozen water and is unable to be used freely: ice that can wash neither hands nor feet. When the mind is melted and is used like water extending throughout the body, it can be sent wherever one wants it.” (Takuan 1986, 32–3)

And this brings us to my personal reflections. In the spirit of full disclosure, I have to begin by noting that I am not a martial artist by any means. My interest in martial arts manuals is purely philosophical. What strikes me about the passages discussed in this essay are two basic insights. First, the description of the three stages of sword fighting, eternal world, internal world, the world that encompasses all, parallels the descriptions of cognitive development, maturation, and transformation in many Buddhist texts. They thus not only outline a route map for self-cultivation, but they also have interesting implications for our understanding of the human mind. Second, and more importantly, this description of the third stage as “immovable wisdom” of the no-mind is immensely appealing. It is through the refusal to focus on one particular thing, emotion, or worldview, as counter-intuitive as it may be, that we become open and able to see “reality-as-it-is.” We realize our common humanity and our kinship with all living beings. This insight has profound moral implications: it calls for social justice to embody the compassion grounded in immovable wisdom. While it is ironic that this may be a lesson of martial art manuals, it definitely is a goal of Buddhist self-cultivation.

* In the Chinese original, the emperor reflects on the oneness of the country, literally, “under heaven” (Ch: tianxia) instead.

References

Stevens, John. 1994. The Sword of No-Sword: Life of the Master Warrior Tesshu. Boston: Shamabala Publications.

Suzuki, Daisetz T. 1959. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Bollingen Paperback.

Takuan, Sōhō. 1986. The Unfettered Mind: Writings of Zen Master to the Sword Master. Transl.: William Scott Wilson. New York: Kodansha America.

Zhuangzi. 2006–19. “Delight in Sword Fight.” Zhuangzi. Chinese Text Project. ctext.org. Last accessed 3 May 2019.