Image courtesy of the artist and Able Fine Art, New York

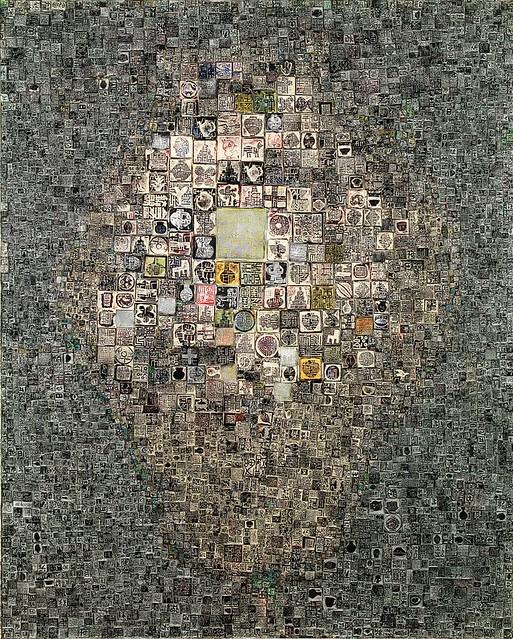

From several yards away, the image is instantly recognizable—the head of the Buddha gazing downwards as if deep in meditation, floating on a background of red. The Greco-Roman facial features, white skin, and bun-like hairstyle evoke the stone and stucco sculptures made 2,000 years ago by artists in Gandhara (covering parts of today’s Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India), a region where many cultures, religions, and artistic styles intersected. Like those of Gandharan sculpted Buddhas, this face is at once calm and powerful. At first glance, it appears to be painted, but as one approaches the image it begins to break down, to pixelate into many tiny fragments, each textured individually. Up close, it is clear that the image has been constructed entirely of hundreds of wooden stamps carved with Chinese characters, small pots, birds, plants, and other motifs, some stained with ink, others left uncolored. Buddha images and carved seals are both significant in the art of many Asian cultures, but their juxtaposition is rare. In his mixed media works, Korean artist Lee Kwanwoo (b. 1969) not only blends sculpture and painting, the ancient and the modern, he also connects the official and the personal, the individual and the spiritual, to create works that encourage viewers to stand still, focus, and even meditate.

Lee began his artistic career studying Western painting at Kwandong University in Gangwon Province, South Korea. As a young artist, he held several exhibitions of his Western-style work, but some 25 years ago, was inspired to create Asian-style imagery by a collection of seals he had discovered as a child in the trash of some empty houses near his home. Traditionally, such seals, carved with the characters of one’s name, have represented identity and authority throughout East Asia. From about 1500 BCE, the Chinese carved simple characters into the faces of seals made of animal bone, metal, and pottery, and for many centuries, nobles and government officials in East Asia have used them to authenticate documents, and scholars and artists have “signed” their paintings and calligraphy using similar stamps. These seals, though small in size, have carried great weight over the centuries, legally, socially, as well as artistically.

Image courtesy of the artist and Able Fine Art, New York

For Lee, the seals he discovered near his home “represented traces of the people who led lives there.” Perceiving in them “a certain eternity,” he felt compelled to preserve them and give them a new significance in his art. He began to incorporate them into sculptural bas-reliefs, building up larger images using the characters and forms carved into the faces of each seal, creating “social relationships and the eternity incarnated through names.” Soon, he began carving individual stamps of his own in varying lengths, widths, and designs and applying them to canvas to create undulating images, from Buddhas and ceramic vases to abstract designs. Inspired in part by his training in Western painting, he has also used his sculptural technique to create copies of paintings by Vincent van Gogh and other European artists. Recently, Lee has also been fashioning stamps of his own design from such 21st century materials as resin.

Image courtesy of the artist and Able Fine Art, New York

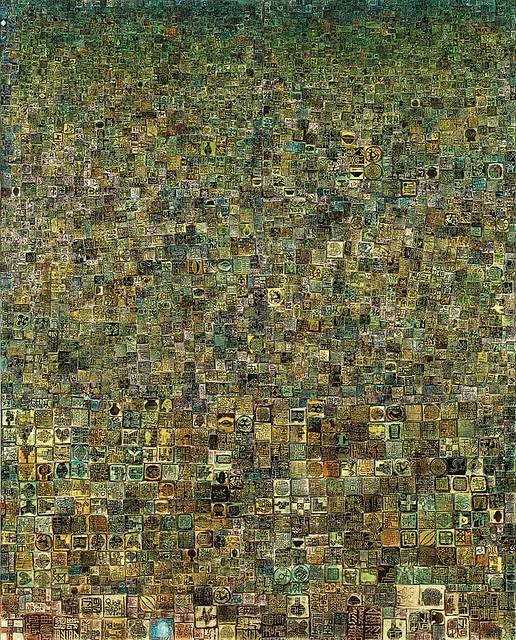

All of Lee’s works of this type—both figural and abstract—bear the title Condensation, suggestive of the action in the material world in which water vapor is transformed into liquid and forms droplets on a window pane or another surface. Although his Buddha faces are some of his most powerful works, his abstract creations are no less spiritual in their tone. Like many droplets of water, these assemblages form meditative mosaics, with hundreds, sometimes thousands, of stamps, each with a unique identity, populating a vast cosmic landscape. In some works, the stamps are arranged in order of size and color so that they draw the eye towards a faraway horizon. In several circular works, his placement of larger, lighter stamps in the “foreground” creates a depth and dimensionality, transforming the circle into a planetary sphere, with a rugged surface that suggests illumination by the sun’s rays. Though often asymmetrical in structure, these densely detailed circles are reminiscent of Buddhist mandalas inhabited by a multitude of enlightened beings. These works also suggest the strength of union—the power of releasing the self into the infinite.

Image courtesy of the artist and Able Fine Art, New York

Perhaps the most mystical of all of Lee’s Condensation works is a 2010 sculptural relief in which larger, lighter-colored stamps, some accented with yellow and red ink, are arranged centrally to form the ghost of a face, probably that of a Buddha. Many of these larger stamps have been carved with the shapes of vases, plants, flowers, and other natural forms, implying the infinite abundance of our natural and material world. However, one square, much larger than all the other stamps, appears empty of a motif, and is embellished with only the faintest of inscriptions. If this ghostly form does represent the head of a Buddha, the large square is positioned at the point on the Buddha’s forehead where his third eye, or urna, would be. The third eye is the point through which the mind of a Buddha is able to connect with the fundamental power and wisdom of the universe. By leaving this space almost blank of the carved inscription that typically identifies and empowers the user of a traditional seal, Lee seems to be inviting viewers to shed ideas of identity and authority for a moment in order to reach beyond the self and connect with something much larger and more powerful.

Lee Kwanwoo is represented by Able Fine Art Gallery in New York and in Seoul. More of his work can be found at Able Fine Art NY.