The circular tea ceremony area was two steps down from floor level, in the sunken center of the living room, wood-floored, set with a low table, cushions, hearth, and tea utensils. We sat in silence in a semi-circle, watching our teacher prepare the tea. Slowly, mindfully, in tune—actions and implements as one.

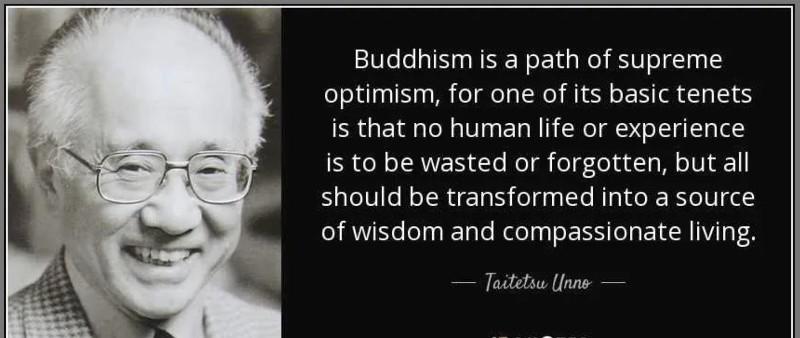

The tea master was my Buddhist philosophy professor, Reverend Taitetsu Unno of the Jodo Shinshu school. We learned a brief history of Buddhism, then each of us focused on an aspect to research and write about. He taught us the “Namu Amida Butsu” recitation, and how to meditate, through posture, mindset, and breath. I was 20 years old. It was all quite foreign to me and I was drawn in completely.

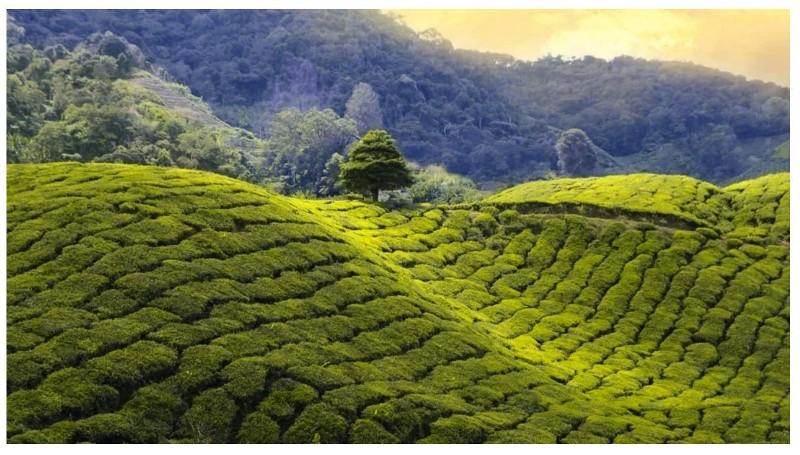

When I was 14, I traveled to Kenya with three other teenage girls to climb Mount Kenya. We were mountaineers. Before the ascent, we had time to explore several villages and other areas, including Meru. One girl’s brother was a tea farmer there, and he toured us around his verdant hills in a Land Rover, proud of what he had managed to cultivate. I had never seen anything so beautiful, whether in person or in the media. I was stunned by the brilliant green, the air, the quality of the place and everything in it, growing exponentially in symbiosis: people, animals, insects, rain, sky, soil, and tea.

When I was 35 years old, I entered a traditional Vajrayana retreat, pulling one foot out of the “real” world, and into the unknown of full-time meditative life. I had been transforming from a two-feet-in-the-ordinary-world state, to one foot in the river of the Dharma and one foot clinging to the known material world. It was time to jump in with both feet, although the water felt icy cold.

Retreat was many things, and one of our coping strategies was tea. We did not have access to much food variety—or quality foodstuffs for that matter—but we could, on periodic breaks, order by mail our preferred teas. There were those, of course, for whom coffee was king. But I am a tea person, always have been. My tastes are simple: a full-bodied rooibos, a pleasant herbal remedy blend, or a simple Earl Grey or English Breakfast. Others were fussier: the exact puerh, steeped just so, or Russian Caravan black, mossy and deep-flavored. Upon waking early, we made our beds and began the first session right after, of course, making our thermos of tea or coffee. For who can meditate without a warm soothing—or stimulating—libation? In fact, the ritual or preparation is itself a meditation.

Nowadays, anytime that lamas or teachers come to teach, we offer them tea. We also offer fine foods, water, flowers, and so on. But we always, always offer tea. At my temple we inquire ahead—do they prefer herbal, green, black, or milk tea? Tea is a sacred aspect of Buddhist hospitality, of respect, honoring, and deference. It is both literal—a beverage to sate the thirst, to warm or cool the body—and symbolic. Of all possible offerings, real or imagined, tea is a universal gift, a show of gratitude and love. As my teacher Tai Unno said: “Meditation is love.” And therefore, receiving teachings on meditation—or view, or action—is also an exchange of love. To request teachings, we offer many sacred articles, both real and imagined. For our teacher to feel welcome, comfortable, and nourished, we offer foods and tea. Of course, we will also bring them a decaf iced latte if we know they prefer that!

A joyous time of year is Losar, the Tibetan New Year. At the temple we serve traditional dishes, and the ubiquitous butter tea, an acquired taste for non-Tibetans. At first, I really could not drink the stuff. But now I enjoy its surprising combination of salty and tannic butter and tea, and the fat that binds them. I remember my dear root lama telling us that a pet name for a partner in Tibetan is nying-tsub, or heart-fat. You are the fat of my heart! Literally, this is the most important, comforting, sustaining part of our literal heart. Hence the deep affection of the term.

I have been buoyed and inspired repeatedly by the stories of wisdom master Dipa Ma Barua, and how she instructed her students by example. I remember a line from her biography, her student relaying that the teacher-saint had asked another student: “Why do you need so many kinds of tea?” This has stuck with me over the years, especially when I read about the popular movement of minimalism and people paring down their possessions. My tea cabinet contains many teas, even when I pare down other areas such as books, clothing, and furniture. Tea is a balm, a companion, a link to tradition, ritual, and hearth. I enjoy my tea choices, but I often remember Dipa Ma’s admonishment and know that one tea is enough.

Tea, like meditation, is something consistent, repetitive, and dependable, a ritual of paying attention to detail, yet also expanding into the whole. The process brings a soothing comfort of familiarity. There is a sense of ownership and ability—heat the water, prepare a pleasing vessel, and use the simple implements with grace and skill. It is something so simple yet deeply rewarding, nourishing, and sane.

Whether you enjoy tea in community, such as a gathering or puja, or in quiet solitude, may your tea sustain and uplift you, body and mind, and may all beings enjoy such complete, though fleeting, nourishment.

See more

Dipa Ma

Butter Tea — Recipe to Make Tibetan Tea: Po Cha

Related features from BDG

Sarah Beasley (Sera Kunzang Lhamo) on Discovering the Treasures of Lineage

Humility, Faith, and Other-Power: Shinran’s “Tannisho”

Kyabjé Tsikey Chökling Rinpoche (1953–2020) – Tender Recollections of a Marvelous Life

Do I Need a Teacher to Practice Meditation?

Some Observations on the Subject of Meditation