When I opened the Escola Caravana (school of mandalas), an online training course in sacred geometry, in 2020, the most common question was also the most important and yet the simplest: what is a mandala? Here I will dare to say that the meaning of the term “mandala” can be as broad and as overused as the word “love,” which depends on who is using it, to whom it is addressed, for what purpose, and in which context. Thus, “mandala,” a Sanskrit word meaning circle, is a universe in and of itself that can mean anything beyond any description.

As such, let us begin with nature, and from there move on to the words of Men. If each mandala is a universe, let us look into how things come to be and then we will lead our contemplation to understand all the various shapes and plays depicted in mandalas.

All that we can perceive in the visible world feels as though it emanates from a mysterious and infinite void. If there is a “God” who created this universe, who or what created this God? We can observe that we simply have no answer, but we know how to witness things coming into being—like a painting that begins with a blank canvas, music that starts from silence, cooking that starts from an empty pan, and a story that begins from no story. In other words, everything starts from zero. But in order to recognize zero, we needed to observe for many centuries, creation and form. The concept of zero came much later, long after we had already learned how to define numbers. We needed a more mature observation of nature to be able to consider the indefinable, the void, and the not-yet-manifested potency of existence, which is as important as everything in the universe.

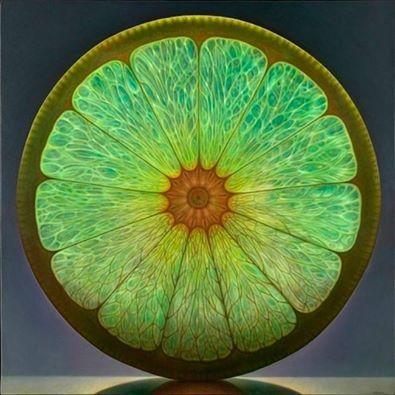

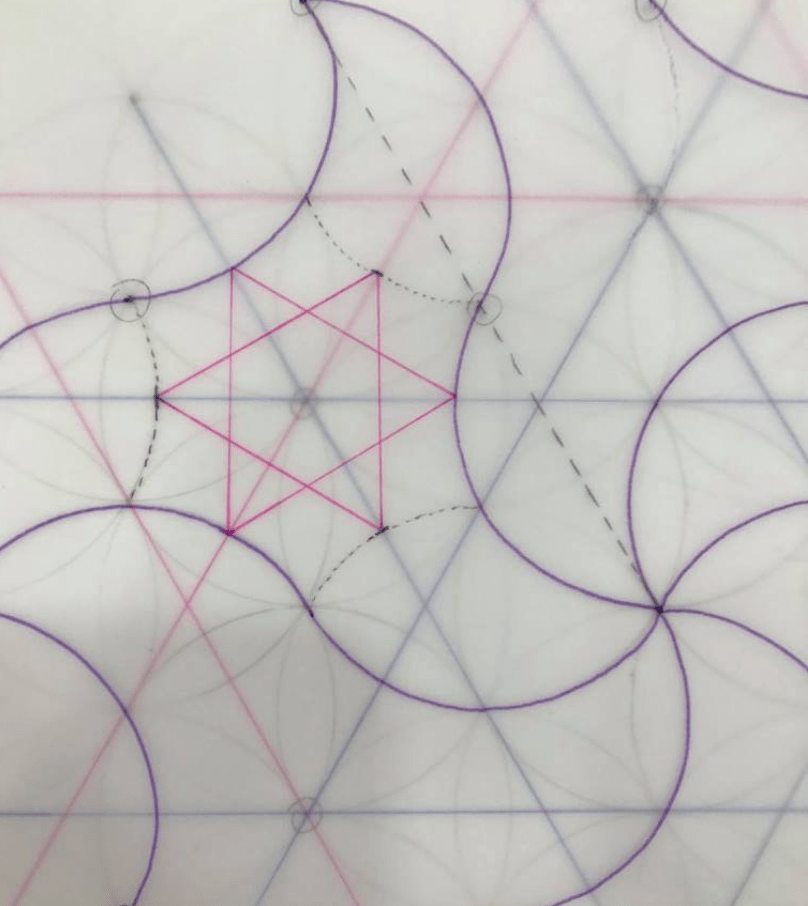

In creating a mandala, we begin by touching the needle of a pair of compasses to a blank expanse of paper. This point is marked by the pressure of the needle but it is invisible and has no dimension or form. Once the compass opens, like an eye that perceives infinity and a mind that stops at some limited boundary, the compass creates a gentle tension between the point of anchor (the needle) and the point of expansion. When it reaches its limit, the compasses turns and creates a perfect circle—the primordial mandala symbolizing creation and the infinity of all possible universes. Any form within the circle is creativity manifesting its unlimited potential: all possibilities, polarities, and the flow of life itself.

From there, the triangle, the square, and all basic shapes come from the circle, which itself emanates from an invisible referential point in space. We can see this reflected in nature: from a tiny seed a huge tree comes to be; from inside the ovum forms a human being; from dust the stars coalesce and shine; from a thought, action and reality are formed. Everything starts in space, from the potent invisible zero, manifesting in unity, and from there multiplying in a myriad myriad ways into all the diversity we know in the world. When we draw mandalas based on sacred geometry, we are “imitating” how all things come to be. But I think that even if we try to draw something with no intention of expressing a mandala, we are still manifesting within the laws of sacred geometry: if you are baking a pie, riding a horse, writing a novel, swimming a lake, each moment you are manifesting from zero and expanding and creating your mandala.

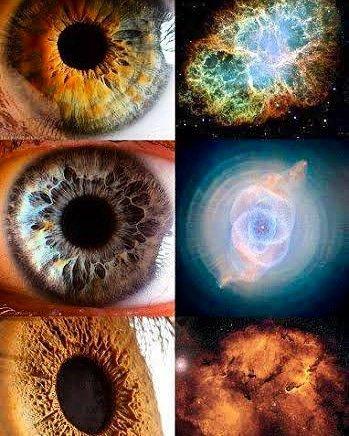

The Big Bang theory makes sense when we think of emptiness, and then a concentrated invisible reference point that suddenly bursts and expands, creating the Many. All objects that came to be and that we know of “imitate” the birth of the universe, and this we can call the fractal effect. A fractal is a representation of anything as a repetition of the source from which it manifests. For example, a broccoli stem divides its shape into a multitude of smaller broccoli stems, which themselves can be seen to divide into tinier broccoli stems. As a kid, I used to hear my father trying to explain broccoli to me: “A tree within a tree within a tree, and you can eat it!” It felt magical and made me feel powerful eating a tree with one bite! (The lengths to which parents will go to make their kids eat vegetables!)

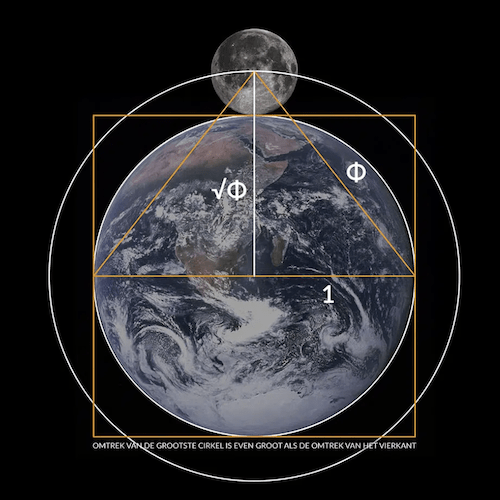

Have you seen images of the cosmos that appear to be expressions of the brain’s intricate neuronal networks? The Moon in front of the Earth, proportionally the same as the ovum and the nucleon of the ovum. Our eyes being round like the planet we live on. And our bodies containing the same proportion of water as our planet Earth. Cells and molecules having the same structures as stellar formations. How from one body, we have five extremities (one head, two arms, and two legs), five fingers, five toes, and five senses? A jasmine flower and the base of a rose and the orbit of Venus each dance in a five-structure matrix, just like a human being. When we view the bigger picture like this, we can notice that we are not so different from a flower or a shell or a planet. The codes of creation unite us, and all this “matter” that we are part of is still an extension of the movement from that first impulse billions of years ago—everything moves from the same original impulse.

This round-world view, connected to an originating center, is probably why we are so attracted to mandalas and probably why so many sacred traditions came to represent some aspect of a higher knowledge of existence and unity through mandalas. We can find many different ways to understand and to work with mandalas in each of these different traditions. In the case of Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala is the abode of the gods, and when initiated by a lama, one can practice entering the mandala through the inner eye of visualization. In Hinduism, mandalas are widely used to represent the bodily chakras and also as symbols of protection and guidance called yantras, which are also related to the pure energy the deities represent. In Islam, although they don’t use the term “mandala,” there are representations that we would recognize as mandalic. These “mandalas” in Islam represent God as an abstract force impulsing creation to manifest infinitely. The construction of Islamic mandalas is based in the codes of nature, such as the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence.

In contemporary life, mandalas have been modernized and used freely as decorations, combining elements of flowers and shapes within a circle that may not mean anything specifically, nevertheless, not matter what we do, we are expressing this underlying sacred geometry, we are fractals of the same movements of the planets and of the five fundamental elements. And while there is a conscious geometry that supports harmony for creation, there is also the geometry of destruction, which is as necessary as the other so that existence can renew itself through the infinite process of birth and death. Yet if we align ourselves toward the codes of nature conscious and are able to “read” them, surely we are accessing a treasure of abundance, beauty, love, and harmony. Having access to the creative tools of sacred geometry enables us to drive, or draw our lives in a more harmonious and intelligent way.

Through creating mandalas in any medium and in any spiritual tradition, one is touched in their hearts, restoring access and inner balance. I have found this to be true when I have the compasses in my hands, drawing circles that cross each other’s centers, forming points of reference that I connect with a ruler creating lines. I feel that I am practicing the pure “ritual” of creation, taking a break from my own distorted views and actions. I can return to the basic, simple, and pure spark of creation, of my own original source. We can come back to the One and the expansion of the limitless Many.

The One and the Many is also discussed in philosophy as the “problem of the one and the many” (there is a lot of content on YouTube about this). But we can also glimpse this wonderful concept in a ritualistic way when we create mandalas. The One is talking about the essence of all things. Like, for example, if your cat disappears, it doesn’t mean that there will no longer be any cats in the world. There is the “cat idea” or essence, which we cannot locate or even define, and which cannot die because it is an idea or an archetype. It is quite an abstract idea and I invite you to open your eyes to comprehend. What makes a cat a cat? If I take away its tail and its legs (sorry), it is still a cat, right? We cannot define what makes a cat a cat—even if there are very different species and sizes of cat, we still know that it is a cat. So there are cats and The Cat. I find myself to be mesmerized by the natural intelligence of it all. Things can die, but the essence of things remains and permeates that mysterious place of ideas, invisible and potent—like an oak tree sitting unmanifested inside a tiny acorn, it is there, in its essence, indestructible.

Basic shapes are closer to the essence. The more attributes and characteristics an object has, the more individuality it manifests. That’s why when we create a logo for a business or organization, it must be simple—simple to access and to express the essence of the message or what the business means. Mandalas in Hinduism, for example, are the closest form to concentrate the deity’s energy. They are like the seed of the god or goddess—potent, pure, fertile, and untouched.

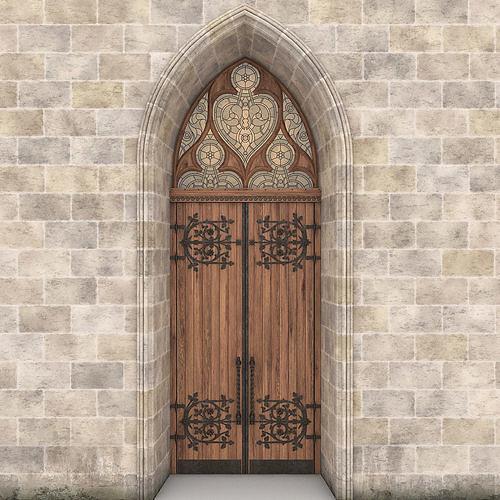

A famous and extremely kind teacher who passed away in 2020, Keith Critchlow, wrote many books on sacred geometry in nature and was the teacher of my teachers. He taught that the circle represents the divine, or the spirit, the square represents earth, or matter, and the triangle is the union of earth and heaven, the spark of things coming together. He noted how these three shapes are mixed constantly in architecture. A box-like room feels different from a domed space, and something within us recognizes this. Although we might not be able to really put the experience into words, we know the difference between entering a tall and round-ceilinged space and a square one. Churches, for example, were deliberately designed and constructed to make visitors feel small before the magnitude of God, to facilitate silence and a meditative mood—whether or not we are religious. We enter shapes and let that shape enter us and touch our soul if it is made for that. Entering a space through a rectangular door that is totally aligned with the horizon, brings us to an earth point of view. A door with an arch brings heaven and earth together, and in a gothic cathedral we see added on top of the door and arch, the triangle, bringing together body (matter), spirit, and mind (triangle).

Scientists have already shown that our brains respond positively to harmonious geometry in the body, in nature, in architecture, and even in music. Conversely, we experience an uneasy response when the same factors are displayed in an unharmonious way. We have difficulty tolerating chaotic, noisy, messy places or people for very long, unless we resonate with the same kind of messiness. In a way, order always finds its way into chaos and vice versa. Nowadays, most of us no longer live in societies that prioritize a connection with the natural rhythms of day and night, eating what grows according to the seasons, touching our feet to the earth, drinking unbottled water, and spending time gazing at the stars. Our ancestors were fundamentally dependent on looking to the stars to navigate and orient themselves on land and at sea. Today, it is almost as if we don’t need nature to know about nature, and this, in my view, is a form of logic that is all out of proportion. We can know, but we are separated more and more from any true experience of nature—the kind of knowledge that is “I just know.” And in the process, we are making our minds and bodies sick from the subsequent increase in suffering.

If we find ourselves living in quite a chaotic society that feeds our bad habits and has an immense gravitational pull, like a blackhole, there is still so much we can hold onto. I am part of this crazy world, and for me my anchor of sanity that makes me wonder and still love this miraculous world and the curious people we are, is to be able to see and create art. One doesn’t even need to be an artist or create anything. The art I am talking about is a state of being, a choice of living, and a point of viewing. For me, creating mandalas based on sacred geometry feels like an anchor of presence, logic, and freedom. It brings sense and beauty to my daily practice and existence. I prefer a life within the mandala of consciousness over the mandala of consumption and capitalism—a very clever geometry, like a blackhole. As individuals, like the individual cells of the same body, we can still choose which mandala we want to be part of.

And so, may I wish you simple beauty, truth, and love in each “compasso” (step) of your life.

See more

Related features from BDG

Opening to Beauty

The Mandala of the Five Dancing Wisdoms within Our Hearts

The Mantras We Say and the Stories We Play