When looking for the “Walking Monk”—the peripatetic Buddhist monk wandering the east coast of Australia—Kerry Stewart from ABC ventured out only to have every “red or saffron object” in sight catch her attention. While bright saffron robes are one universal sign of a Buddhist monastic, the garments can in fact come in a diverse selection of both colors and styles. So, how did this simple garb develop over the years?

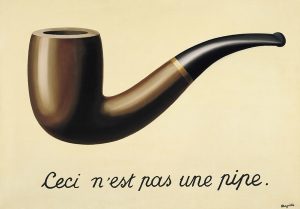

Presumably, one can trace the development of monastic clothing back to the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. In a comprehensive talk by Candana Karuna, who was ordained in 2008 in the Vietnamese Lam Te (Rinzai) Zen tradition and is a member of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship and Sakyadhita: the International Association of Buddhist Women, she discusses the humble beginnings of monastic clothing and its evolution in more recent times. When the Buddha, overcome by life’s questions and trials, decided to become a “mendicant seeker” (one who forgoes his possessions and relies mostly on charitable donations from others), he readily took to wearing a simple robe, created from scraps of cloth (Skt. pamsuda or pamsula), wrapped around his body. These pieces of cloth were scavenged, trimmed, cleaned, and even dyed, resulting in a slight discoloration or “murkiness” to the final robe. In Sanskrit, this earthy-toned garment was called a kashaya, which can be defined as “mixed” color or “color that is not pure.” Candana Karuna says that she has also been told that “it refers to colors considered ugly, colors chosen to renounce that culture’s values.”

During the time of the Buddha’s enlightenment and teaching, the robes had no code and mostly followed the kashaya’s serviceability. However, when the Buddhist king Bimbisara had difficulty distinguishing monks from laypeople, the Buddha asked for a new robe to be designed that would resemble rows of paddy fields. From this first, dare I say, Buddhist “fashion-designing” project, the “triple robe” (Skt. tricivara) was created. It had three parts—a regular clerical robe (Skt. uttarasanga), a lower robe (Skt. antarasavaka), and an additional robe (Skt. sanghati) that was used for warmth, bedding, and so on. From these beginnings, the Buddhist robe morphed and took on different meanings in terms of styling and colors as Buddhism reached other countries far and wide.

Depending on the Buddhist school and lineage as well as region, a monastic’s robes vary greatly. Those in the Theravada tradition wear saffron, ocher, or bright orange following the Buddha’s own kashaya. The name “Theravada” derives from Sthaviriya, one of the early Buddhist schools. Both the outer robe and under robe worn by Theravadins are made from cut pieces of cloth and must not come from a single piece of cloth.

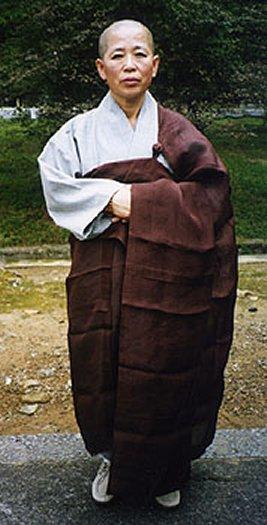

The robes of those ordained in the Mahayana tradition are more diverse, mainly due to geographical and climatic differences. Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Mahayana followers generally wear simple robes, with a cloth collar around their necks. While the robes of Chinese and Korean monastics are brown, gray, or blue, those of Japanese monks are black or gray. Religionfacts.com also says that Japanese monks wear a special prayer robe over their usual robes, which is made from patches of silk brocade. The prayer robe’s special pattern is said to mimic the Buddha’s patchwork robe, and “like those of a mandala, the geometric patterns are said to symbolize the universe.”

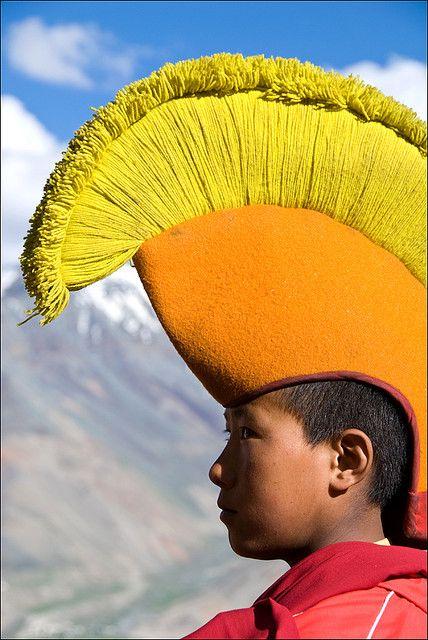

Echoing the rich Buddhist art of Tibet, the robes of practitioners in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition can be more colorful. Tibetan robes are usually maroon in color, mainly because in the past, red was the cheapest dye that could be bought. The basic garments for a Tibetan monastic are the dhonka (a wraparound shirt, either in maroon or maroon and yellow with blue piping); the shemdap (a maroon long skirt); the chogu (resembling an extra robe that covers the upper body); the zhen (an everyday shawl in maroon); and finally, the namjar (a larger silk cloth used for ceremonies, either in gold or bright yellow). The Tibetan tradition, flamboyant as ever, also makes good use of hats. Among other things, these denote lineage; for example, red hats are worn by the Nyingmapa school and yellow hats by the Gelugpas. Nuns’ robes are basically the same as those of monks, with a few additions.

The simple monastic robe encompasses what we lack nowadays: versatility, homogeneity, simplicity, and basic functionality all in one. At least for me, it is quite refreshing to see an individual strip away all the brands, colors, styles, shoes, hats, skinny jeans, blazers (and so on—every day a new trend appears!), and have no qualms or complaints . . . rather, just being thankful for what covers them day or night, summer or winter, during celebrations or any regular day. In modern times, it isn’t uncommon to even see monks and nun in sports shoes, or wearing a watch or a nice pastel-colored sweater to combat the cold (and maybe match their robes . . . let’s call it coincidence!)

Robes, Ralph Lauren, a raincoat, or a scarf in rouge . . . take your pick!

For further information, see:

The Tradition of Buddha’s Robe