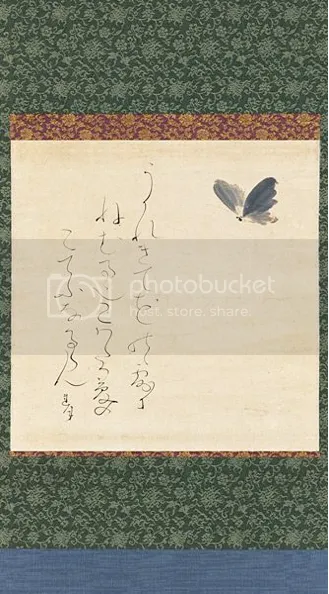

“Fluttering Merrily” by Otagaki Rengetsu, Japan, 1840s–50s, calligraphy and painting in ink on paper mounted as a hanging scroll; Private Collection, Switzerland

Cho

Ukarekite

Hanano no tsu ni

Neburu (nemuru) nari

Ko wa taga yume no

Kocho naruramu

Butterfly

Fluttering merrily and

Sleeping in the dew

In a field of flowers,

In whose dream

Is this butterfly?

(by Otagaki Rengetsu; translation by Kuniko Brown)

The above poem, alluding to the famous existential conundrum of the Chinese Daoist sage Zhuangzi, is inscribed on scrolls, ceramic cups, and bowls by Otagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875), a Japanese Buddhist nun and one of the country’s most respected female artists. Although Zhuangzi was a Daoist, his question “Am I a man who just dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly now dreaming he is a man?” also resonates powerfully with Buddhists, for whom reality is believed to be an illusion. Rengetsu, whose life was full of tragedy before she became a nun and an artist, used her art to probe the mysteries of life and reality. A calligrapher, poet, and ceramic artist, she blended these three art forms to create a unique body of work in clay and on paper that is at once painfully personal, light-hearted, and deeply spiritual, and expresses the wisdom of a woman who lived through many different realities.

Born in Kyoto, and probably the illegitimate child of a courtesan and a noble, Nobu (her given name) was adopted by the samurai Otagaki Teruhisa and his wife. As a child, she was sent to Kameoka Castle near Kyoto to serve as a lady-in-waiting; there, she trained in the traditional arts of calligraphy, poetry, and dance. Nobu was a woman of great beauty and married twice, bearing five children, all of whom died. At age 33, undoubtedly heartbroken by the loss of so many of her loved ones, she vowed never to marry again and joined her elderly father at the temple Chion-in in Kyoto, where she became a nun and took the name Rengetsu, which means “Lotus Moon.”

After her father’s death in 1832, Rengetsu left the temple and had to find a way to support herself—a rare situation for a woman in Japan at the time. She decided to try to make a living as an artist, and drew upon her childhood training in poetry and calligraphy. She was a very skilled poet in the traditional waka (literally “Japanese song”) form, most typically short poems or tanka, consisting of 31 syllables arranged in five lines of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables (from which the later haiku form was derived). Despite the brevity of this poetic form, she was able to express profound emotion, as in the following verse. Inscribed on exquisite paper printed with colored designs of chrysanthemums, it is a sad reminder that Rengetsu lost all of her children when they were very young:

Umi no ko ni

Ii nokoshiken

Mogokoro no

Hana ni yukashiki

Sakurai no sato

To my own children

Words remain to be said,

The flowers of sincerity

Bring back old memories

In Sakurai village.

(by Otagaki Rengetsu; translation by Kuniko Brown)

Rengetu’s calligraphy is in the kana style, a highly cursive form that was originally used by Japanese court ladies to write love letters and poetry, in contrast to the more block-like kanji, or Chinese characters, typically used by men for historical records, government documents, or religious texts. Her slender and fluid style gained her the reputation of being one of Japan’s finest female calligraphers. Her mastery of poetry and calligraphy made her very welcome in Kyoto’s literati circles, where she was often invited to inscribe her verses on the paintings of the most celebrated artists of the day.

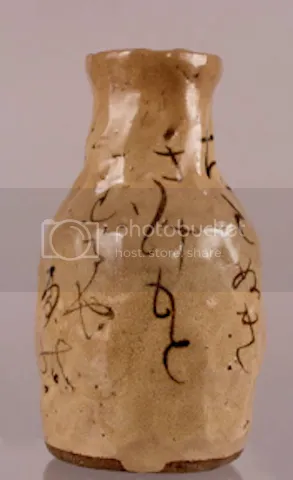

Although she was well respected for her poetry and calligraphy, it was by inscribing her poems onto ceramic vessels that Rengetsu became truly unique as an artist. She learned from potters in Kyoto how to hand-build pottery, and went on to decorate her rough and rugged bowls, cups, and other vessels with her poetry, either painted on or scored into the clay in delicate, feminine calligraphy. Despite—or perhaps because of—their amateur forms and irregular surface texture, Rengetsu’s ceramics, or Rengetsu-yaki, were so popular during her lifetime that it is said that every household in Kyoto owned some, and orders from tea masters and other customers kept her very busy. Primarily tea utensils, flower vases, sake bottles, and cups, her ceramics were even duplicated by forgers, with copies passed off as her work. According to one legend, Rengetsu actually helped some forgers by writing her calligraphy on their bowls and cups.

Among her various ceramic creations, Rengetsu is perhaps best known for the exquisite vessels she crafted for both the chanoyu and sencha traditions of tea-drinking. Rengetsu created many tea bowls, or chawan, for the more traditional tea ceremony, chanoyu, some with steeper sides to keep tea warm in winter and others with a shallower, more open form that allows the tea to cool in the summer. Her tea bowls and other ware for the chanoyu tea ceremony often bore verses with Zen Buddhist themes, such as the following verse about the transience of life on a winter tea bowl:

Kawa

Yono naka no

Chiri mo nigori mo

Nagarete wa

Kiyoki ni kaeru

Kamo no kawa mizu

River

This floating world’s

Dust and dirt

Flows away

And all is purified

By the waves of the Kamo River

(by Otagaki Rengetsu; translation by John Stevens)

She also created many bottles, flasks, and cups for another important beverage—sake. As with her other ceramics, Rengetsu’s sake ware is adorned with her own poems, inscribed in her exquisite calligraphy. Unlike some of the more contemplative verses on her scrolls and tea ware, the verses on sake bottles and cups often reflected the more light-hearted mood of sake-drinking:

Furutanuki

Sake motomuruya

Ame no yo no

Sono tsurezure no

Susahi(bi) naruran

Old Badger

Asking for sake

This is the pleasure

Of leisure hours

On a rainy night

(by Otagaki Rengetsu; translation by Kuniko Brown)

The tanuki (a badger or raccoon dog) is a trickster character in Japanese folklore who knocks on doors at night in search of a drink of sake, typically disguised as a Buddhist priest. By alluding to this sneaky character who puts on a Buddhist disguise, Rengetsu reveals her playful side, hinting perhaps at her own identity as a Buddhist nun and suggesting that this, like all of her other identities and the varied realities of her complex life, is simply an illusion.

Meher McArthur is an Asian art curator, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles. She has curated over 20 exhibitions on aspects of Asian art. Her publications include Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols (Thames & Hudson, 2002), The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles (Thames & Hudson, 2005), and Confucius: A Biography (Quercus, London, 2010; Pegasus Books, New York, 2011).