The West is not yet awake to the power of thought.

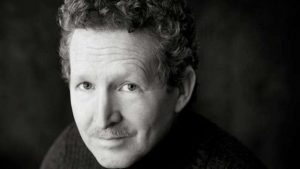

Christmas Humphreys

In 1924, at the age of 23, Christmas Humphreys founded the London Buddhist Society, which has since become one of the largest Buddhist organizations outside of Asia and certainly in the United Kingdom. Humphreys served as its president for nearly sixty years, his tenure ending only with his death. The society he established has the honor of having the Dalai Lama as its current patron and continues offering ongoing classes, workshops, meditation opportunities, a magazine and a website with a wide variety of resources.

Christmas Humphreys was born on 15 February 1901, and was christened Travers Christmas Humphreys. The unusual name “Christmas” was traditionally used in his family for more than two centuries. His parents, however, called him “Toby” and he was referred to that way throughout his life by family and friends. It was the death of his brother, Richard, which activated Humphreys’ interest in Buddhism. Richard was serving the in the army during World War I and was killed in Belgium. Describing the impact of his brother’s death, Humphreys recalled, “The wound went much deeper than a schoolboy’s learning of a beloved brother’s death. . . . From that hour I began a journey and it has not ended yet, a search for the purpose of the universe, assuming it has one, and the nature of the process by which it came into being.” (Tricycle)

Along with studying law at Cambridge University, Humphreys began researching and reading books about Buddhism which were readily available at the university libraries. By the time he graduated with his law degree, he had fully committed himself to the Buddhist path. In his day, he was the best known British convert to Buddhism.

Establishing the London Buddhist Society was initially a humble start. Humphreys and his wife simply used their London home as the first “headquarters” offering meditation and Buddhist discussions on Monday evenings. In his autobiography, Both Sides of The Circle (G. Allen & Unwin 1978), Humphreys explains that attendance was unpredictable and intermittent. He and his wife would prepare and wait for people to arrive but on many Monday evenings no one would come. Though his professional career was the practice of law, first as a barrister and later as a High Court Judge and QC, Humphreys’ main interest and livelihood was Buddhism. Along with guiding the London Buddhist Society where he hosted various spiritual teachers, Humphreys’ began wrote dozens of books including Zen: A Way of Life (Little, Brown & Co. 1962), Buddhism: An Introduction and Guide (Penguin Books 1951), and An Introduction To The Buddhist Way of Life For Westerners (Schocken Books 1970).

Aware of the Christian culture in which he lived, Humphreys found ways to explain how Buddhist practices differ significantly from Christian ones. For example, in his classic, Concentration and Meditation: A Manual Of Mind Development (Stuart & Watkins 1968), he outlines the difference between Christian prayer and Buddhist meditation:

Most Westerners are born and bred in Christianity, and have in early years been habituated to the practice of prayer. The word has many meanings, varying with the spiritual development of the individual, but save in the true mystic its essence is always supplication to some external Being or Power. In meditation, however, there is no such element of importuning, of begging for what one has not. At the best the method of prayer is a yearning of the heart; meditation, on the other hand, re-orientates the mind, thereby producing the knowledge by which all that is rightly wanted is acquired. The meditator does not ask for guidance, for he knows that a purified mind can call upon the Wisdom which dwells within.

When introducing people to meditation, Humphreys began by saying there were specific “rules or maxims” to be kept in mind for meditation to become, “an entrance to the way of enlightenment and not merely an intellectual pastime.” Here are his six rules:

1. Do not begin unless you mean to continue. Here he challenges those who are unable to make a serious commitment but are merely curious about it’s benefits. “Meditation is not a hobby, and it is unwise to trifle with so serious a subject,” he writes. The effort must be continuous and consistent if one expects to see positive results.

2. Beware of self-congratulations. All too frequently, modest advances in one’s meditation practice can begin to breed pride which can lead to arrogance. “When the first well-earned results of mental training begin to manifest, beware of the separative effect of self-conceit,” he states and adds: “All too soon a little success in the inner life will breed a sense of superiority over one’s fellows, a sense of separation from those (apparently) less advanced upon the Way. Therefore be wary lest too soon you fancy yourself a thing apart from the mass.”

3. Avoid guru hunting. His concern is over those who are constantly seeking out teachers in order to speed up their spiritual growth. “The Western world is filled with those who seek for ‘Masters,’ ‘Gurus,’ and other mysterious personages to lead them swiftly to the goal.” There are no short cuts and a person must proceed with self-discipline on the spiritual path. “Beware, then, of this craving for assistance, for it is born of laziness and conceit and is in turn the father of disappointment and delay,” he warns.

4. Ignore psychic experiences or the appearance of psychic powers. Many beginners in meditation perceive auras, hear sounds, and experience new sensations. While these may be valid, he cautioned against attaching too much importance to them. “Let not the student be fooled by their enchantment. To waste one’s precious time in cultivating psychic powers is to sidestep from the Path of Self-Enlightenment. These powers will be useful at a later stage, but for the time being are best ignored.”

5. Learn to want to meditate. Most people do not find it easy or natural to sit in meditation. It is a desire which must be consistently directed. Humphreys explains it: “Unwilling work is badly done, and there is less waste of effort and a higher standard of workmanship in exercises carried out with the whole soul’s will than in those which are the outcome of a habit forced on an unwilling mind.”

6. Do not neglect existing duties. Once meditation does become a regular and pleasurable habit, Humphreys warns against allowing the practice to displace other important responsibilities connected to family, work, relationships. “It has been said that meditation is first an effort, then a habit, and finally a joyous necessity,” he says citing a common progression. “When the third stage comes, beware lest the discovery that it ranks in interest and value far ahead of earthly pursuits and happenings should lure one from the due performance of the daily round.”

After retiring from the law profession in 1975, Humphreys energetically continued his work with the London Buddhist Society literally until his last breath when he died suddenly from a heart attack. He was 82 and had just begun sitting for meditation with a group of friends.

WORDS OF WISDOM FROM CHRISTMAS HUMPHREYS

Once the feet are turned towards enlightenment the heart’s attraction to the world is left behind.

The very system of thought we know in the West as Buddhism is based on the supreme enlightenment gained by the Buddha in meditation; how else, then, shall we attain the same enlightenment if we do not follow in the self-same way?

The practice of meditation tends to remove the fetters of suffering by raising the consciousness to a level above its sway.

The way of meditation is the way of knowledge, and the aim of all such knowledge is to find and identify oneself with the Self within.

The West is not yet awake to the power of thought.

The Buddhist’s purpose in life is to raise the quality of living as distinct from the standard of living, to eliminate the self which hides the light of his own Enlightenment rather than to improve the comfort of his worldly life.

It is an astonishing fact that very few people think, though many think they do.

When the act is complete, decide whether or not you wish to remember it. Many pride themselves on a

marvelous memory; others are just as proud of the ability to forget. Why carry about through life a tremendous burden of old memories?

How pleasant are the truly great who, wanting nothing, are content with anything.

Far too little thought is given to the art of relaxation, yet never has it been more necessary than in these days of ceaseless dissipation of energy.

I must accept myself for what I am before I can deliberately change it.

Each one of us is hard at war – within. We must face this battlefield and realize that we should be so busy killing the selfishness within that we really have not the time, much less the will to blow up our neighbor.

Attempts to blame all will be found of no avail, and we must learn to withdraw them. None other is to blame for our body, home or circumstance, our friends and enemies, our job and place in the world. We made it all; let us accept and use and better it.

See more

Christmas Humphreys (Tricycle)

Related features from BDG

Buddhism in Britain, Part One: Encountering British Buddhists through sociology and ethnography

“Homeless” Kodo Sawaki: From Brothel Worker to Buddhist Monk

The Man Who Brought Buddhism to Great Britain: Allan Bennett

Robert Aitken: From POW to Zen Master

I was once a distance member of The Buddhist Society and can thus be said to have benefitted from Christmas Humphreys’ work. Here, however, are a couple of dissenting voices for balance:

https://authory.com/NeilRoot/a690fb3b3b71e42c2a23d99f937f5a4e7

https://buddhistsocialism.weebly.com/how-christmas-humphreys-reinvented-buddhism-in-his-own-image.html