Situated on the southern Eurasian steppe to the northwest of the Caspian Sea, Kalmykia is an autonomous republic in the Russian Federation. It is the only region in the geographical vicinity of Europe where Buddhism is historically practiced by its titular population, the westernmost branch of the Mongolian peoples. The Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism has been the most practiced among the Kalmyks since the time of the Kalmyk khanate, a polity formed on the northern Caspian in the mid-1600s by Oirat Mongols, migrants from the Junggar basin and ancestors of the present-day Kalmyks.

Khosheutovskii Khurul (the Temple of Victory) is the only Kalmyk Buddhist temple that has partly survived from the pre-Soviet era. Ironically, it is situated not in Kalmykia, but in the neighboring Astrakhan region. This has not always been the case. Before the devastating deportation of the Kalmyks and the official abolition of Kalmykia in 1943, a substantial part of what today is Astrakhan Oblast, including the site of Khosheutovskii Khurul, belonged to Kalmykia. Even after the restoration of Kalmykia within the Soviet Union in 1958, this territory remained in Astrakhan Oblast.

Anti-religious campaigns in the Soviet Union erased the Kalmyk Buddhist establishment, at least from the public scene. In Kalmykia, Buddhist monasteries and temples are referred to by the word khurul, literally meaning “assembly.” This terminological ambiguity makes it rather problematic to estimate the exact number of monasteries in the Kalmyk region in the pre-revolutionary period. Of approximately 100 khuruls and more than 2,500 monks in Kalmykia around the early 1920s, all khuruls had ceased to exist by the beginning of World War Two, most monks having been arrested and forced to disrobe. Monastery property and premises were confiscated, destroyed, or used for other purposes, including being demolished for building materials.

Across the vast and empty landscape of the steppe, the only remaining structure attesting to the Kalmyk Buddhist past is the central chapel (süme) of the Khosheutovskii monastery complex. The temple has a fascinating history, with numerous legends and miraculous events connected to it.

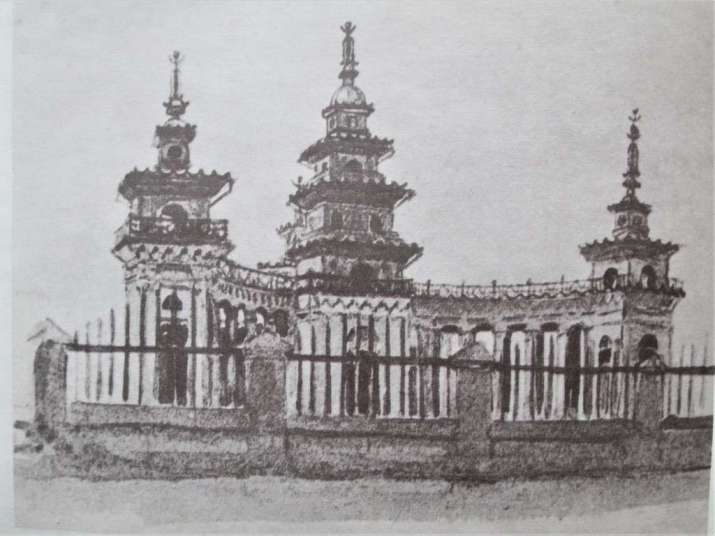

Khosheutovskii Khurul was built during 1814 and 1818 in remembrance of the Kalmyk participation in the war with Napoleon (known in Russian history as the Great Patriotic War of 1812). It was constructed in stone in an architectural manner similar to Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, which is dedicated to the Russian Orthodox icon Our Lady of Kazan. The initiator and main sponsor of its building was the Kalmyk prince Serebjab Tümen, the commander of the Second Astrakhan Kalmyk regiment in 1811–14, while the designers of the architectural project were Serebjab’s brother, Batur-Ubushi, and Gavan Jimbe, a Kalmyk monk who is said to have traveled to Tibet.

An established account has it that in the summer of 1814 Batur-Ubushi came to Saint Petersburg, having been invited by the Tsar Alexander I to celebrate his victory over the French. The main site of the celebration was Kazan Cathedral, as it had become the memorial to Russian military achievements in the Napoleonic war (the Russian commander-in-chief Mikhail Kutuzov was buried there in 1813). Another variant of the story states that both Tümen brothers, Batur-Ubushi and Serebjab, came to Saint Petersburg.

Whichever scenario is more accurate, Batur-Ubushi was greatly inspired by the curved colonnades of Kazan Cathedral, the shape of which may have reminded him of the family seal (Kalm: tamha) of the Tümen princes, which was represented by a stretched bow with an arrow. It is said that he had the idea of having a Buddhist temple in the form of a bow built in his native region on the Volga. Serebjab supported this initiative, with construction beginning the same year.

Every brick used for the building of Khosheutovskii Khurul had the Tümen seal imprinted on it. When I was at the site of the khurul in the summer of 2012, it was still possible to see the original bricks with the seal. The main temple of the Khosheutovskii monastery was definitely among the largest Kalmyk Buddhist edifices. Its architectural ensemble consisted of a central three-nave tower and two symmetrical semicircular galleries ending in smaller tower-chapels. While inspired by the architecture of Kazan Cathedral, it was not meant to be its mere replication, but combined elements of Russian classicism and Tibetan Buddhist architecture. Its distinctive element, which later developed into a visible feature of pre-revolutionary Kalmyk Buddhist architecture, is a completion of tower-chapels with pinnacles in the form of stupas (traditionally called suburgan in Kalmykia), vertical Buddhist monuments containing relics.

It was the fourth stationary monastery built in Kalmykia as, until the 1800s, Kalmyk khuruls had been predominantly movable and accommodated in yurts (ger), the Mongolian nomadic dwelling. Soon after its construction, the khurul (with approximately 670 monks) became an important Buddhist center on the Volga, famous for its rich library of Tibetan manuscripts and vast collection of Buddhist art. According to Aleksei Pozdneev, a Russian Mongolist of the 19th century, the khurul had 80 thangkas and 27 statues of deities, as well as numerous Buddhist musical instruments. While some of these were brought from Tibet, Mongolia and possibly other Buddhist centers abroad, others were made by local artists and artisans.

Having participated in military campaigns in Europe, Prince Serebjab brought new foreign habits to the Kalmyk steppe and arranged his life in what he saw as the “European way.” This included building a big mansion for himself and promoting a sedentary lifestyle among his peers. He is also said to have enjoyed welcoming guests from abroad, with visiting the khurul and listening to a large Buddhist orchestra among his main entertainments. In 1858, Aleksandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers, visited Serebjab and was greatly impressed by this Buddhist monastery on the Volga. Among his other well known guests was German polymath and naturalist Aleksandr von Humboldt, and numerous Russian ethnographers, writers, and architects. Even Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik revolution, is said to have visited the site of Khosheutovskii Khurul with his wife, Nadejda Krupskaia, although Prince Serebjab had died by then.

During the so-called “cultural storm” and Soviet anti-religious campaigns, the khurul ceased functioning as a Buddhist establishment and was used throughout the following decades for other purposes, gradually falling into ruin. In the 1930s and 1950s, the main temple of the former monastery was used as a kindergarten, a youth club, a school, and then as a granary. In the early 1960s, its side chapels and galleries were dismantled for bricks used to build a cowshed for the local state farm. Only the central tower-chapel outlived decades of anti-Buddhist policy, although there were plans to dismantle even that for building materials.

The survival and surprising indestructibility of Khosheutovskii Khurul, unlike other Kalmyk Buddhist structures, is locally explained by a popular legend. I heard this rather shocking story for the first time from Lama Balji Nima, the head of the khurul in the village of Tsagan Aman, situated across the Volga from Khosheutovskii Khurul. During its construction in 1814, the ground suddenly began to slide toward the Volga and the walls of the central tower collapsed. This recurred several times, making it impossible to continue construction. The monastery astrologer came to the conclusion that it was necessary to make a special sacrifice to the local “owner of the land,” presumably a deity. The main offering had to be a young boy born in the year and month of the tiger.

In the Kalmyk lunar calendar, the month of the tiger, or leopard, corresponds to December. The legend, however, does not specify the deity demanding the sacrifice. One can presume it could be the White Old Man (Kalm: Tsagan Aava), venerated among the Oirats and Mongols as the owner of all land and water, or the equestrian warrior deity Däächin Tenggr, worshipped in Kalmykia as a war god and perceived as abiding in national banners.

Accordingly, it is said that a young child from a poor family was chosen (or kidnapped from Russian peasants, according to another variant of the legend, as the boy for the sacrifice had to be blond) and mounted on a white stallion. He was then bricked alive behind a wall of the central chapel of the unfinished temple. It is this sacrifice that allegedly made the khurul impossible to be completely destroyed, having compelled the local deity to become its powerful guardian. I have been told that all those who tried to dismantle the central part of the temple in the 1960s died soon after—or even during—their unsuccessful attempts at demolition.

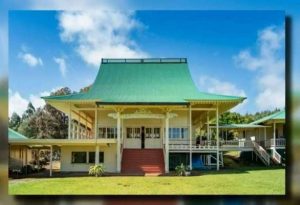

With the advent of freedom of religious expression, which marked the beginning of the Buddhist renewal in Kalmykia in the late 1980s, Khosheutovskii Khurul (or rather what had been left of it) was recognized as an object of federal importance, and the leaders of Astrakhan and Kalmykia, as well as the Russian Ministry of Culture, agreed to its restoration. Re-consecrated as a Buddhist temple in 2004, its renovation was completed only 10 years later. The side chapels and galleries, however, have not been reconstructed. One can only hope that the original bow-shaped structure will be restored in the future, which currently appears problematic and costly.

Although situated outside what today is officially defined as the republic of Kalmykia and not reconstructed in its original form, Khosheutovskii Khurul remains a sacred place for the Kalmyks, being a locus of Kalmyk socio-historical memory—memories of powerful Kalmyk princes, military successes, and beautiful Buddhist monasteries on the Volga steppe, together with bitter memories of the darkest pages of Kalmyk history during the Soviet era. While having been built to commemorate the victory in the war of 1812, the khurul is undoubtedly an embodiment of the victory of the Dharma on the Volga and the icon of Kalmyk Buddhist revitalization.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Cultural Autonomy and Spiritual Revival in Kalmykia: A Conversation with Valeriya Gazizova

Buddhist Holy Sites of the Russian Steppes

The Dalai Lama’s Visits to Kalmykia

Kalmykia: Lore and Memory at the Far Side of the Buddhist World

The Kalmyk Restoration: Telo Tulku Rinpoche on a Russian Republic’s Buddhist Revival