Powerful deities are often hidden in plain sight. For many immersed in Buddhist lore, the realm of the nagas is very significant. These half-serpent, half-human beings are present in the natural world. For others, the serpentine appearances are almost unseen or at the most, simply tied in with one particular deity or myth. You may have seen the snake heads protruding from many a Buddha crown or the great Shakyamuni statues with the cobra Mucalinda protecting him as he reached enlightenment. These images tend to be more about the central figure, the Buddha, and Mucalinda merely representing, usually symbolically, a certain mythic or aesthetic part of that narrative.

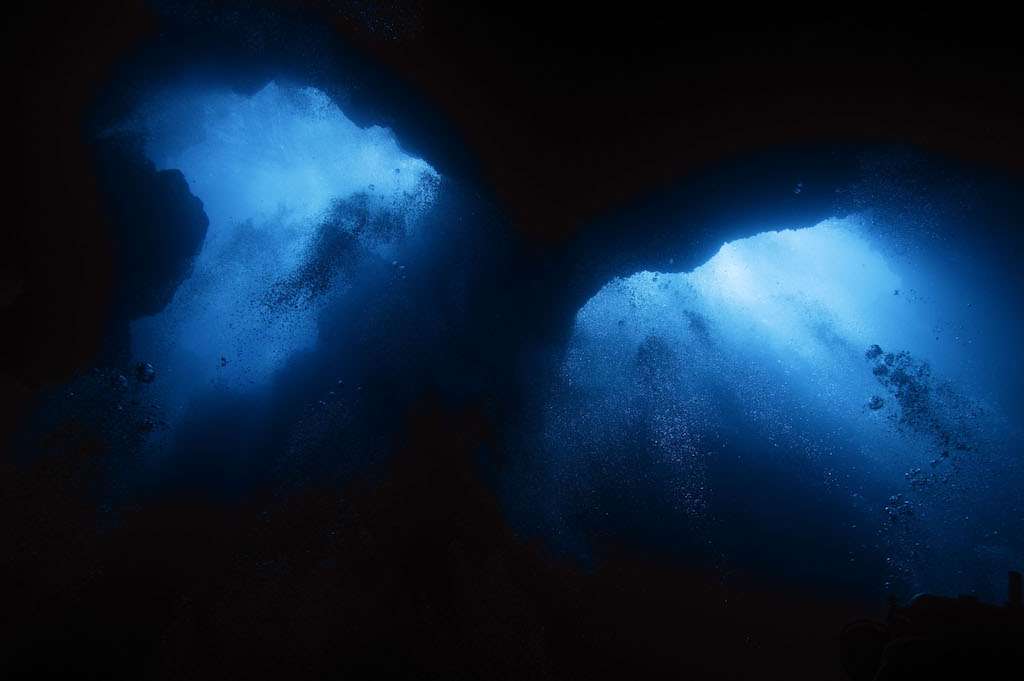

The nagas appear malevolent in some stories, in opposition to the noble bird-like deity Garuda. Conversely Mahayana practitioners see them as benevolent deities lurking in cavernous underwater palaces, and as such they are often seen flanking the doors of sacred spaces. In religious imagery, snakes are also typically seen sitting around the neck of a supreme being, as in Hinduism’s Shiva, or wrapped around the stomach or even as an adornment of a great deity. Beyond Buddhism or Hinduism, the snake is apparent in nearly every religion, spiritual practice, and country around the world. And like many before me, I wondered why.

While I am a researcher and artist with a deep-rooted proclivity for symbolism, I’m far from an expert in the field of ophiolatry (serpent worship). I’m merely hitching a ride on the shoulders of those wiser than I. However, what this open view does afford me is space to muse upon the vastness of this hallowed yet much maligned icon in sacred art. My question for deeper thought is simple: is there a common theme behind the mythical stories that evolved around the serpent? Can we draw back the veil and see a message in the art, and what might it say to us when we feel its presence? We’ll look a little into how serpent worship has been interpreted over the millennia, diving into deep history and travelling around the world before circling back to the deeper messages I’ve postulated.

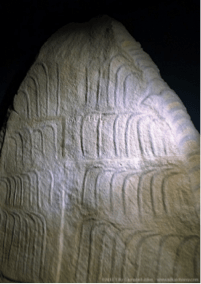

Snake cults appear to be one of the oldest and most prevalent forms of worship on the planet. A confluence at varying points in time and place seems to have occurred between primal, localized “shamanic” practices and institutionalized religious practices, with the serpents being enveloped into the folds of new hybrid persuasions. One of the oldest enduring beliefs is the rainbow serpent of Aboriginal Australia, the creator rainbow that is related to water and arches in the sky like a snake, and promising water and life to parched lands. We also know that serpents and dragons are found in architecture and art around the world. We see them at the ancient carvings at Göbekli Tepe. The Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl is a fertile creator god. The Nordic Jörmungandr appears in various Eddic poems. The Ancient Egyptian “rearing cobra,” the Uraeus, was a symbol of divine rulership, while the chaos serpent Apep terrified the pharaoh’s subjects. Snakes appear at Chichen Itza and the medical symbol of Asclepius’ staff. The list is global.

Why were the ancients so fascinated and what were they trying to convey in their imagery? Some conspiracy theories say that we are all descendents of some serpentine, reptilian race. What is certain is that snakes are ubiquitous creatures and many weild a lethal venom, so perhaps the ancients placed them on a godlike pedestal because of a primeval fear of their bite. Since the snake also holds the cure for its own poison, the handlers, possibly through mithridatism (the practice of protecting oneself against a poison by gradually self-administering non-lethal doses), might have seen the creature as almost superhuman. The heroic legends and feats of serpent- or dragon-slaying might derive from folk memories of subduing or slaying venomous snakes that were killing livestock or tribe members.

Such pragmatic thinking might lie behind the frequent appearances of snakes in art, but how did such reverence and awe make the leap to outright worship of the serpent, or ophiolatreia, in so many regions around the world?

There are those who suggest that the serpent represents sexual energy, not least as it has been thought to be indicative of male genitalia, often by the phallus worshipers found in a few parts of the world. In India, we have the Hindu lingham, and there are male fertility festivals in Bhutan, Japan, and ancient Egypt. Evidence of this possible phallic serpentine relationship is also found in Brittany, France, with the granite Menhir de Champ in Dolent at Dol-de-Bretagne and interesting carvings found down in Carnac, the vishap (Vishapakar) stones in Armenia, and erect rocks in Cappadocia, Turkey.

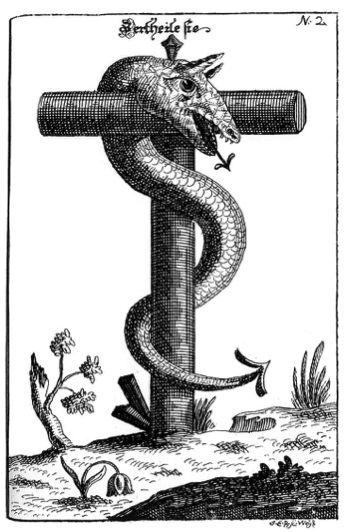

Almost all serpentine stories mention a staff, typically indicative of our spinal column, with the snake pictured wrapping around it. Many claim that it is Kundalini or Shakti energy represented, since the serpent coils its way seven times up the chakras ascending our backbone. Could it symbolize the dual nature of reality or brain hemispheres, as the double helix shaped snakes also ascend the central rod as in the Grecian caduceus? The cobra encircled itself seven times around Gautama as he reached enlightenment before protecting him from seven days of storm. Similarly, serpents have been portrayed with a world tree, and tree worship is also thought to be one of the earliest subjects of worship and viewed as feminine, so perhaps this was an obvious marriage of early symbols representing fertility. But the serpent is also often wrapped around an egg or eating its own tail, protruding and protecting a deity, or held and subjugated somehow.

It is curious that nearly every great god or goddess has a serpent as their familiar, and that aside from its phallic association by those aforementioned, if we go back far enough to more gender egalitarian times, back to ancient Egypt, we find that they are often actually considered a feminine energy when the sun was still considered the ultimate feminine creator. For this reason I have been referring to the serpent as “her.”And if it were ever obvious, childbirth is the most obvious example of creation, so perhaps it should be no surprise that archaeological evidence suggests that ophiolatry seemed to accompany Mother Goddess worship. But why is the snake considered creative?

We know the snake is a glorious representation of resurrection thanks to its skin sloughing and reemerging in a shiny new one, which does have an sense of rebirth about it. This ecdysis, or skin shedding, rendered snakes an embodied example of personal creation, personal alchemy. And with this “new self” generally comes some wisdom, embodied in the serpent. Is it a coincidence that of all his teachings that the Buddha said humanity was not ready for, it was the Prajnaparamita texts? And of all candidates to safeguard them it was the watery naga who protected the scriptures until they were revealed to Nagārjuna and these ultimate wisdom texts became personified as the motherly embodiment of wisdom—Prajnaparamita?

I am sceptical of the patriarchal contexts in which many scriptures were written, so while the teachings are inherently valuable, in my next article I’ll be looking at some creational stories but with a view behind the names and genders, and then further back to art and artifact to see what else is lurking in plain sight.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Iconography of Nagas, Part Two: Syncretism and Science

The Iconography of Nagas, Part Three: DNA in History

The Iconography of Nagas, Part Four: Chaos and Creation

Hi Tilly, are you aware of the symbol for Saint John; a Serpent entwined around a chalice.

Great piece! I think you may enjoy this article which argues that snake venom is an entheogen, that helped them become self-aware. https://vectors.substack.com/p/the-snake-cult-of-consciousness