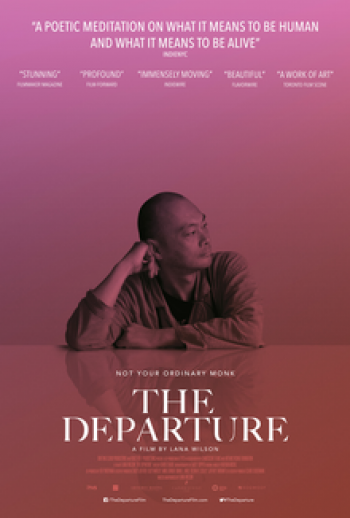

It is an unfortunate but well known fact that Japan has a high suicide rate. According to The New York Times, between 1998 and 2011 “there were more than 30,000 suicides each year—one nearly every 15 minutes.” In fact, suicide is so common that during unexpected stops between train stations, passengers often assume the delay is caused by a person jumping onto the tracks. What is more, in Japanese culture suicide can be seen as a moral and even necessary act when it comes to preserving one’s honor and integrity. In the documentary The Departure (2017), filmmaker Lana Wilson follows Ittetsu Nemoto, a monk who is deeply perplexed by this phenomenon and who, in offering his services to those who experience suicidal ideation, goes against the grain of Japan’s social norms.

Upon its US release in 2017,* the film was critically acclaimed, nominated for Best Documentary at the Independent Spirit Awards. The atmosphere and pacing are certainly enchanting: Wilson makes use of long, still shots, and the contrast between periods of silence interrupted by everyday sounds (footsteps on gravel, lights being turned on, clothes coming off the hanger) augments the sensation that we are watching Nemoto’s life as it naturally unfolds. Adding to this impression is the fact that Nemoto appears to exist both as a monk and a layperson. Indeed, Buddhist monks in Japan are not constrained by the same strict monastic rules as other traditions—they can marry and have a family, wear casual clothes, eat meat and drink alcohol—so Nemoto’s punk-rocker roots are apparent in his everyday life. While he wears traditional robes during formal teachings at the temple, he sports a casual urban outfit (a beanie hat, baggy pants and shoulder bag) when he meets people in the community. We also see him leave his family in the evenings to attend nightclubs, and he jokes with a member of the temple that he has had a drink every night in the past week. Nemoto even came to monkhood in a casual manner; with an earnest smile he explains that his mother came across a newspaper add looking for monks with “no experience required.”

As I watched the film, I initially found myself questioning whether Nemoto was doing the right thing by the people he counseled. Having worked as a healthcare professional, I have undergone extensive suicide-prevention training and the importance of using non-judgmental language has been impressed upon me. For this reason, I couldn’t help but recoil as Nemoto counsels a man whose short monthly visitation rights with his children lead him to vocalize his desire to die, saying: “It would be too much pain for your kids to bear if you committed suicide on them. The bereaved of those who commit suicide can’t escape the pain for the rest of their lives.” As I understand suicide prevention, such a response does not serve a suicidal person: the man’s current feelings of despair and shame at not being a “good” father are likely to be further compounded by Nemoto’s remark that suicide would be harmful to his children. And indeed, the result is that the man, whose face is covered in tears, is silenced and unable to carry on the discussion.

And yet the more I reflect on the film, the more I respect Nemoto in his attempts to alleviate the suffering of others. For one thing, his cultural upbringing means that he has had little to no formal instruction on dealing with suicidal individuals. In a review of The Departure, Ken Jaworowski says: “There isn’t much talk therapy in Japan—if you go to a psychiatrist, he will usually see you for just a few minutes and give you a prescription. Nemoto wanted to help suicidal people talk to each other without awkwardness . . .” (The New York Times)

This cultural lack of a safe space to talk about suicide is visible in a scene where Nemoto provides assistance to a suicidal young lady. What starts out as an amicable discussion between the girl, her grandfather, and Nemoto quickly turns unbearably awkward as Nemoto addresses the girl’s depression. The grandfather, who is clearly uncomfortable about the topic, tells Nemoto that the girl should be stronger. “You should solve your own problems,” he says. “You shouldn’t depend on others.” Yet Nemoto perseveres and offers his unconditional presence and support to both the girl and her grandfather as they suffer.

Nemoto’s ability to be present with the people he counsels is admirable, as is his innovation. Lacking a societal framework within which to address suicide, he creatively comes up with his own methods: from having individuals reflect on how it would feel to give up what they treasure most (one participant writes, “the bed my grandfather gave me”) to facilitating movement therapy activities and group talk therapy, the monk relies on trial and error to find what works best for each individual. What is more, this is a man struggling with his own health issue—he is diagnosed with unstable angina and is told by his doctor that he is at a high risk of having a heart attack—yet he continues to serve others at the expense of his own health. The monk’s exhaustion is apparent in close-ups, and he often expresses awareness of his own shortcomings. He jokes with the man who has restricted child visitation rights that they should create a “bad father alliance,” explaining that he too is failing his son because he spends such little time with him (a common theme throughout the film). “I’m sorry,” he tells another woman who is in the midst of despair. “I’m not being much help, am I?”

Nemoto’s humanity is refreshing. All too often monks are expected to embody the pinnacle of enlightenment, yet we tend to forget that they too encounter successes and failures along their path. Instead of being preachy, Nemoto is relatable; he is a reminder of the human weaknesses and strengths that we all share, and his wish and determination to alleviate suffering is deeply inspiring.

* Film Premiere: Powerful New Documentary Follows the Life of a Buddhist Priest Dealing with Suicide (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Review: In ‘The Departure,’ Watching Over Those Who Flirt With Death (New York Times)