It was 1959. A young housewife was driving across America, from the open fields of the Midwest to the rugged Pacific Coast. Angie Boissevain and her husband were moving to central California, an area known for its beautiful coastline and wild foothills. In their first years there, they would pick a random spot on the map and drive the winding roads of the Santa Lucia Mountains, exploring their new home.

On one such excursion, seeking a hot spring, the couple took a “long, tiny road” that eventually dead-ended at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, the first Zen monastery established outside of Japan. Welcomed into the zendo, the couple listened to a talk by Suzuki Roshi, the founder of the center, sat zazen for the first time, and enjoyed a delicious meal. Boissevain knew she had found something special.

“I got up at 4am and sat with the students. It just felt like I had found where I was supposed to be,” Boissevain recalls. The couple returned to the Zen Center many times over the ensuing years.

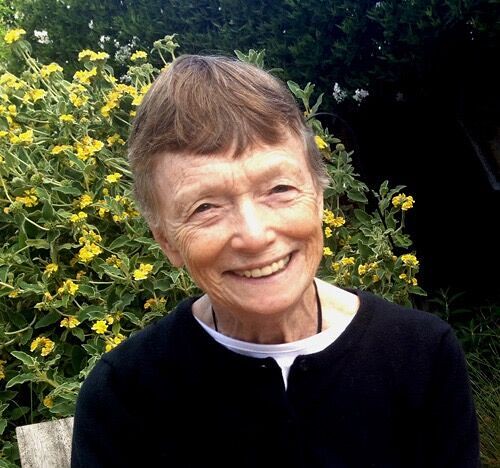

While continuing to embrace her role as a wife and mother, Boissevain had found a second home in Zen. She eventually grew into an accomplished teacher in her own right, studying with Kobun Chino Otogawa and helping to found Jikoji Zen Center, in the coastal Santa Cruz Mountains. As director and teacher there, she helped expand the practice of Soto Zen in the West. She now teaches with Floating Zendo in San Jose, California, as well as with students remotely around the world.

By the 1970s, the young mother had been practicing off and on at Tassajara while raising a family. “We had three little children at home,” she recalls, and she balanced life as a mother with her Zen practice. That’s when Kobun Roshi, a teacher in the lineage of Suzuki Roshi, moved in around the corner from her house.

Haiku Zendo, a small center in the San Francisco area, was populated mostly by “little old ladies and Stanford [University] students,” and Kobun Roshi came once a week to give Dharma talks. Intimidated yet intrigued, Boissevain had found her teacher. “I was very shy in those days,” she recalls. “I hardly talked to anybody; I just crept around and tried to go every Wednesday night” to the talks.

Studying Zen, she says, transformed her life as a mother “in every way.” The Dharma isn’t separate from life, but seeps into and affects every aspect of lay life, including motherhood. Her teacher eventually gave her the title of “enlightened housewife”—a title that Boissevain says she initially bristled at. “I was incensed!” she says, laughing. Boissevain recalls her teacher, intending a compliment, saying that he had never thought a woman other than his own mother could be enlightened. “I, being ferociously feminist, thought that was wrong, wrong, wrong!” Boissevain says.

Kobun Roshi’s method of explaining the Dharma, and his trust in Boissevain as a student, meant that she had studied large portions of the sutras within a few short years. He then entrusted her and several other students to help establish a new zendo in the Santa Cruz Mountains: Jikoji Zen Center, where she became a teacher.

In buying the property, the Zen center inherited “a little commune” of houses in the woods. The residents ended up at Jikoji in the early days. “It was quite a chaotic place,” Boissevain recalls. “Kobun said we should invite them to come and sit with us.” Her early years at Jikoji were spent learning to practice and live among diverse people, sharing lunch with an ex-convict, sitting zazen with a military veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, studying sutras with runaway teenagers. It was an exercise in building family and community that was completely new, challenging, and essential.

After all, sitting zazen is not always a peaceful exercise, Boissevain notes. “Sometimes trauma comes up. Zazen is not going to make a trauma go away, but it’s a gift. Whatever comes up is a gift. We need to know what’s in us, what pours through us like a river.”

One aspect of practice that has flowed through Boissevain’s life is language. She is also a poet. Although she herself has been dedicated to study, she warns beginning students against spending too much time immersed in words.

“Studying is ‘like trying to learn to swim by reading a book,’ Kobun used to say. You don’t do that; you go in the water!” she exclaims. “[Reading] is not a personal exercise in trying to gobble up information. It’s not about memorizing new stuff; it’s about opening yourself to the minds of wise others.”

For many years, Boissevain traveled and taught in the US and Europe. She was receiving Dharma transmission from Kobun Roshi when he died suddenly in 2002, and received her full transmission in 2004 from another of his students. “I feel very attached to my lineage just because it’s so different. Kobun’s way of expressing the Dharma was so different from most teachers. I appreciate that so much that I feel sort of possessive of it,” she says. Despite her desire to share the teachings, she sees the lineage inherently changing as it comes to the West, spreads, and finds new students.

“I’m very different from my teacher,” she explains. “I’m a Midwestern housewife; he’s a Japanese man who was raised in a Zen temple. There’s no comparison in that sense. But, ultimately, transmission really means every moment of every meeting that we are having with anything, with the trees and the grass and the stars. It’s how we are able to openly meet whatever we meet.”

Now semi-retired after a recent surgery, she teaches in California with Floating Zendo, meets with students over tea, and sifting back through the “50 years of poetry” she has floating around the house. Using Skype to stay in touch with students helps her keep relationships alive “in a wonderful way.” And of course, she still sits, first thing in the morning, every day, in her house in San Jose, coming back again and again to the practice that has been a part of her home for so many years.

See more

Tassajara Zen Mountain Center

Jikoji Zen Center

Floating Zendo

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Who Am I — Self-discovery in Japanese Zen Practice

A Vow Without a Wristwatch: Jan Chozen Bays

Meditations in Light by Echo Lew