My late Noble Friend in the Dhamma Prof. Lily de Silva, head of the Department of Pali at Peradenya University in Kandy, Sri Lanka, once wrote an essay titled “Giving in the Pali Canon” (1995), which provided an erudite explanation of the Buddhist term dana (giving). Having a panoramic overview of the Tipitaka, and knowing the Pali texts inside out and backwards, Lily was in a good position to elucidate clearly, concisely, and coherently on what the Buddha said on the topic of dana, which will be the subject of this essay, albeit paraphrased, condensed, and compacted.

“Dana, giving, is extolled, in the Pali Canon, as a great virtue. It is, in fact, the beginning of the path to liberation,” Lily explained.

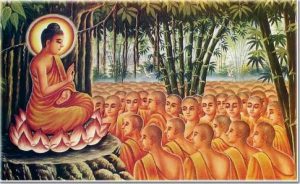

Dana is the first of the ten perfections of an arahant on the path to nibbana. When the Buddha teaches, he begins his sermon with the virtues of giving (danakatha). (Vin.i,15,18) Of the three wholesome bases for the performance of meritorious deeds (punnakiriyavatthu), giving is the first, the other two being virtue and mental cultivation. (A.iv,241)

Giving is of prime importance in the Buddhist scheme of mental purification because it is the antidote to greed (lobha), which is the first of the three unwholesome motivational roots (akusalamula). Greed is wrapped in the selfishness of egoism because we grasp tightly onto our personalities and our possessions—to be “I” and “mine.” Giving helps to eradicate a sense of self and is the means to eliminate egocentricity and greed.

“Overcome the taint of greed and practice giving,” exhorts the Devata-samyutta. (S.i,18)

It is difficult to exercise this virtue of giving proportionate to the strength of one’s selfish greed. The Devata-samyutta, the first division of the Samyutta Nikaya, equates giving to a battle (danan ca yuddhan ca samanam ahu, S.i,20). One has to fight the evil forces of greed before one can make up one’s mind to give away something coveted and useful to oneself.

Someone lacking spiritual strength finds it hard to give up a thing to which he or she is accustomed. (M.i, 449). A small quail may come to death if it becomes entangled in a weak creeper, which is still too strong for a little bird, while for an elephant, even a heavy iron chain would not be a strong bond. Similarly, a wretched person of weak character would find it hard to part with meager belongings, while a monarch with a strong character might even give up an entire kingdom once understanding the toxic nature of greed.

It is not only miserliness which prevents giving. Heedlessness and ignorance of the causes of kamma and survival after death can likewise be determining factors (macchera ca pamada ca evam danam na diyati, S.i,18). One who understands the moral advantages of giving will be vigilant in seizing opportunities to practice virtuous actions.

The Buddha once said that if people knew the value of giving the way he did, they would not eat a single meal without sharing it with others. (It.p,18).

The suttas (e.g. D.i,137) use various words to describe qualities of donors: They are people of conviction (saddha); they believe in the moral and spiritual perfection of humans. They have faith in the nobility of a moral life, in the teachings of kamma, and in survival after death. They are not materialists. They have faith in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha. They are not merely givers (dayako), but lordly givers (danapati)

The commentary explains the concept of the “lordly giver” as follows: “He who himself enjoys delicious things but gives to others what is not delicious is a donor who is a slave to the gifts he gives. He who gives things of the same quality as he himself enjoys is one who is like a friend of the gift. He who satisfies himself with whatever he can get, but gives delicacies to others is a lordly giver, a senior and a master of the gifts given.”

Those who maintain an open house for the needy are a worthy donors (anavatadvaro)—a refreshing spring (opanabhuto) for recluses, brahmins, the destitute, wayfarers, wanderers, and beggars, and thus performs meritorious actions. Such people are munificent (muttacago) and interested in sharing their blessings with others (danasamvibhagarato).

Such a person is a philanthropist, feeling compassion for the plight of the poor (vadannu).

Such a person is open-handed and ready to comply with another’s request (payatapani).

Such a person is worthy of asking (yacayogo).

Noble givers are happy “before, during, and after giving.” (A.iii,336) Before giving, they are happy, anticipating the opportunity to exercise generosity. While giving, they are happy to be making another happy. After giving, they are satisfied that they have performed a good deed.

The Buddha compares a person earning wealth righteously and sharing it with the needy to someone who has two eyes, whereas a person who earns wealth but does not share it is comparable to someone who has one eye only. (A.i,129-30) Wealthy people who enjoy their riches alone without sharing are digging their own graves. (Sn. 102)

Practically any useful thing may be given as a gift. The Pali Canon lists 14 items suitable to be given as dana. They are: robes, almsfood, shelter, medicine plus food, drink, cloth, vehicles, garlands, perfume, unguent, beds, houses, and lamps as requisites for the sick. (ND.2,523)

It is not necessary to have much to be generous; one gives what one can, dependent upon one’s means. Gifts given from meager resources are considered valuable (appasma dakkhina dinna sahassena samam mita). (S.i,18); dajjappasmim pi yacito. (Dhp.224)

If a person leads a righteous life, living just on gleanings, giving from limited resources, but providing the best he can for his family dependent on scarce means, such generosity is worth more than a thousand sacrifices. (S.i,19-20)

Almsgiving from wealth righteously earned is praised by the Buddha. (A.iii,354; It.p.66; A.iii,45-46) A householder who gives alms will be lucky in the hereafter. Even if one gives only a small amount with a heart full of faith, one will gain happiness hereafter.

The Vimanavattha of the Khuddaka Nikaya supplies more examples. According to the Acamadayikavimanavatthu, the alms consisted of a little rice crust, but because it was given with devotion to an eminent arahant, the reward was rebirth in a magnificent celestial mansion.

The Dakkhainavibhanga Sutta on the Analysis of Almsgiving (MN 142) states that an offering is purified when the giver is virtuous on account of the recipient; when the recipient is virtuous on account of both the giver and the recipient, if both are virtuous; or by none if both are impious.

Lastly, in conclusion, comes dhammadana, exceeding all other forms of giving. By sharing and disseminating the teachings of the Dhamma, one is helping others to understand and righteously follow the path to nibbana. There is no form of giving (dana) that is higher.

See more

The Buddhist Attitude Towards Nature by Lily de Silva (Access to Insight)

Dana: The Practice of Giving – selected essays edited by Bhikkhu Bodhi (Access to Insight)

Sadhu Sadhu Sadhu 🌷